Penguin

Michelle Smith, Deakin University

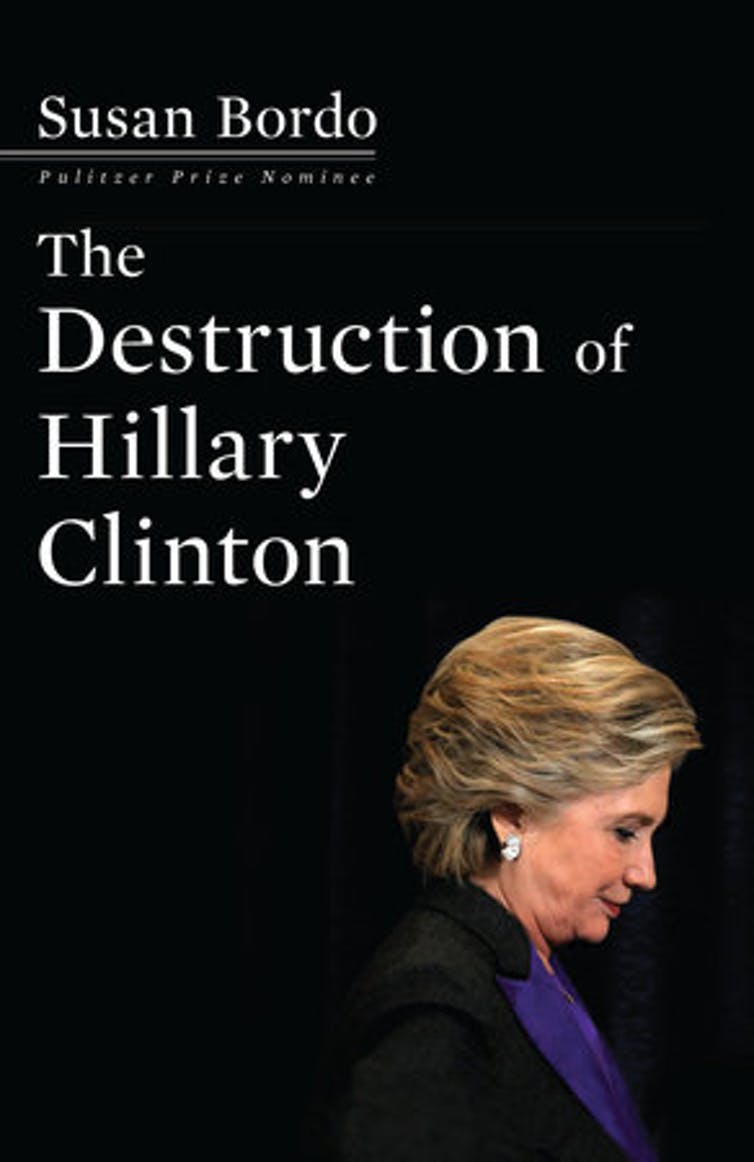

Susan Bordo’s response to Hillary Clinton’s unimaginable defeat at the hands of Donald Trump reads like a bystander’s account of a train crash or bomb explosion. In the wake of the unexpected, and what feels like destruction, how can the exact cause of the catastrophe be explained?

Bordo takes rapid stock of the situation — completing the book’s epilogue the day after Trump’s inauguration — to explain how the highly-qualified Presidential candidate had her reputation systematically dismantled.

Gender is one obvious factor that impacted upon how Clinton’s achievements and experience were degraded. Bordo calls her “a living Rorschach test of people’s nightmare images of female power”. While the viciousness of the diatribe ramped up from her 2008 campaign (exhortations to “Make Me A Sandwich” transformed into putting “the bitch in jail”), the role of sexism was roundly denied from all sides of politics.

As in the case of former Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard, to pinpoint the operation of sexism on how Clinton was being judged was labelled as “playing the woman card”. Frustratingly, this was not solely confined to conservative men, with many young women considering “women’s issues passé”. The construction of Clinton as part of the white, privileged “establishment” meant any notion of “sisterhood” was abandoned in favour of support for Bernie Sanders.

Bordo’s claim, however, is that sexism alone was not the explanation for Clinton’s defeat. She sketches a picture of a woman who could have sprung from the pages of “a gruesomely illustrated version of a Grimm’s fairy tale”.

It is this “caricature” of Clinton, “forged out of the stew of unexamined sexism, unprincipled partisanship, irresponsible politics, and a mass media too absorbed in ‘optics’ to pay enough attention to separating facts from rumors, lies, and speculation”, who lost the election. Trump, she claims, did not beat a “real person at all”.

To chart the mythological processes that created the imaginary, villainous Hillary, Bordo begins by examining the concessions she had to make from the moment her “radical feminism” was seen to have cost her husband, Bill Clinton, the election for governor of Arkansas in 1980. Some of Sanders’ supporters questioned her progressive credentials. Why did Hillary Rodham eventually adopt her husband’s surname and make other concessions to playing the role of supporting wife (including wearing make-up).

Women of the Baby boomer generation, like Bordo, generally appreciate the contradictions and barriers implicit in the movement from the ideal of the “happy homemaker” to the “liberated woman” that occurred during their youth. As Bordo puts it, the girls of her generation shared the experience of growing up in a period

within which one cultural notion of what was required of girls was supplanted, virtually overnight, by another.

Clinton is of the first generation of women for whom becoming a lawyer, let alone a President, was roundly possible. How easily have we culturally dismissed the fact that this process of change from the “happy homemaker” ideal is still in progress, with lingering expectations of how women should ideally behave in conflict with the qualities we expect of (male) leaders.

As Bordo points out, the demands on women who have a public profile are significantly different, “physically and emotionally”, to those for men. In a crucial moment during her 2008 presidential campaign, Clinton’s “warm tears” during a public appearance conveyed just “the right degree of feminine vulnerability, ‘softness,’ and ‘accessibility’” without compromising expectations of competence and strength.

Female politicians are locked in a tussle between competing ideals. Yet they are also critiqued for displaying the same behaviours that are acceptable in men. While Sanders could “bellow” at rallies as a sign of political passion, women who speak loudly “raise the spectre of a punishing mommy”.

People from both sides of politics attempted to explain that the problem with Hillary was not that she was a woman. It was simply that she was the wrong kind of woman, unlike Elizabeth Warren. Yet in 2014, as Bordo shows, a Times/CBS News poll found that 82% of Democrats supported Clinton above Warren and Joe Biden. Even Ohio voters placed Clinton above the six likely Republican candidates in a Quinnipiac poll.

There was a clear difference in perceptions of Hillary as Secretary of State who left office with a 69% approval rating, and Hillary as an actual contender for the leader of the United States. Bordo explains how her term as Secretary of State was soon recast and distilled into “‘Benghazi’ and then ‘the email scandals’”.

Most significantly, this account situates the reworking of Hillary’s achievements and minor errors into the devious schemes of a fairy-tale witch alongside the bizarre forgiveness of Trump for much greater crimes.

Even the force of more than a dozen women alleging that Trump sexually harassed them could not eclipse the manufactured outrage over Clinton’s legal use of a private email server.

The false picture of who Clinton was, aided by the mainstream media, convinced almost five million Obama voters not to vote at all or to vote for someone else other than Clinton.

Bordo’s explanation for how these voters — not misogynists, not automatic Trump voters — came to see “elitist”, “corporate whore” Hillary as unsupportable is important for us all to digest, especially if we ever hope to see a woman lead the United States.

If we continue to accept black-and-white characterisations of powerful women as wicked, then we might be waiting a very long time.

Michelle Smith, Research fellow in English Literature, Deakin University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Advertisements Share this: