It was 1920 and America was gripped with fear. The country was under siege by moral perverts bent on destroying goodness, virtue and the American way of life. Spawned by the Russian Revolution of a few years earlier, the Red Menace was upon us.

Where was an American hero who would do something — build a wall, perhaps, to keep out the Bolsheviks, anarchists and labor militants not to mention Mexican rapists and murderers? U. S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer stepped to the fore. On this day in 1920, he dispatched federal agents to pool halls, restaurants and private homes in thirty-five American cities (sanctuary cities?) to round up some six thousand radicals. No warrant? No problem. Civil liberties were meant for true Americans.

Where was an American hero who would do something — build a wall, perhaps, to keep out the Bolsheviks, anarchists and labor militants not to mention Mexican rapists and murderers? U. S. Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer stepped to the fore. On this day in 1920, he dispatched federal agents to pool halls, restaurants and private homes in thirty-five American cities (sanctuary cities?) to round up some six thousand radicals. No warrant? No problem. Civil liberties were meant for true Americans.

“The nation owes a debt of gratitude to A. Mitchell Palmer,” said the New York Herald. “And now let there be no mawkish sentimentality about these rascals, no prattling of the sacred right of free speech from parlor socialists and others of that ilk.”

The near hysteria subsided in a few months when Palmer’s “imminent revolution” was a no-show, but ethnic profiling and guilt by innuendo had been let out of the bag. Perhaps, they would wither and die here? Or perhaps not. Among the army of federal agents unleashed by Palmer was a 24-year-old staunch anti-Communist fanatic named J. Edgar Hoover.

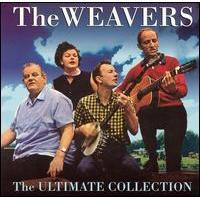

They’re Not Folk, They’re Fellow Travelers

The Weavers burst onto the popular music scene in 1950. The group, founded in 1948 by Pete Seeger along with Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman, brought a hard-driving string-band style to a mix of traditional folk songs from around the world, blues, gospel music, children’s songs, labor songs, and American ballads. Their recording of “Goodnight Irene,” held the Billboard #1 spot for 13 weeks that summer.

The Weavers went on to sell millions of copies of songs such as “Midnight Special” and “On Top of Old Smoky” at the height of their popularity. Then as fast as their careers had skyrocketed, they were nearly destroyed by the Return of the Red Scare, this installment brought to us by the jovial Joe McCarthy. When it became known that Seeger and Hays had openly embraced the pacifism, internationalism and pro-labor sympathies of the Communist Party during the 1930s, the backlash was swift and brutal. Planned television shows were canceled, the group was placed under FBI surveillance, and Seeger and Hays were called to testify before McCarthy’s House Un-American Activities Committee. The Weavers lost their recording contract with Decca in 1951, and by 1953, they were barred from television and radio and unable to book concert venues. They soon disbanded.

The Weavers enjoyed a comeback in the late 1950s, but the group never shook its right-wing persecutors. Even as late as January 2, 1962, with anti-communist passion declining, their politics were used against them, On that afternoon they were told that a scheduled appearance on The Jack Paar Show would be canceled if they didn’t sign an oath of political loyalty. Every member of the group refused to sign.

Lee Hays died in 1981 shortly after a reunion brought the wandering minstrels back together for a picnic that led to a triumphant return to Carnegie Hall on November 28, 1980, the group’s last ever performance. Pete Seeger never stopped singing until his death in 2014. Ronnie Gilbert died in 2015, Fred Hellerman in 2016.

Lee Hays died in 1981 shortly after a reunion brought the wandering minstrels back together for a picnic that led to a triumphant return to Carnegie Hall on November 28, 1980, the group’s last ever performance. Pete Seeger never stopped singing until his death in 2014. Ronnie Gilbert died in 2015, Fred Hellerman in 2016.

“If you can exist, and stay the course — not a course of blind obstinacy and faulty conception — but one of decency and good sense, you can outlast your enemies with your honor and integrity intact.” Fred Hellerman, accepting a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award for the Weavers in 2006

♦

It’s a great country, where anybody can grow up to be president … except me. – Barry Goldwater, born January 2, 1909 (died 1998)

It’s a great country, where anybody can grow up to be president … except me. – Barry Goldwater, born January 2, 1909 (died 1998)

Advertisements Share this: