By Drew Baumgartner and Ryan Desaulniers

This article contains SPOILERS. If you haven’t read the issue yet, proceed at your own risk!

Remove everything that has no relevance to the story. If you say in the first chapter that there is a rifle hanging on the wall, in the second or third chapter it absolutely must go off. If it’s not going to be fired, it shouldn’t be hanging there.

Anton Chekhov

Drew: I feel like we tend to talk about Chekhov’s Gun backwards: we often frame it as “a gun introduced in the first chapter must go off in the third,” but that “must” kind of scrambles the causality — guns don’t go off in narratives because they’ve been introduced; they’re introduced because they need to go off. If the gun doesn’t go off, it’s as irrelevant to the narrative as the rings of Saturn. It’s an essential concept for narrative efficiency, but my awareness of it undoubtedly influences my own understanding of what a story is. While a child may think of a story as “everything that happens to the characters between the beginning and the end” (I know I did), anyone familiar with Chekov’s Gun must recognize that a good story is, at the very least least, pared down to only the relevant events transpiring between the beginning and the end. It’s a notion that assures us that whatever we’re reading is important, which in turn provides some clues about what the narrative finds important. 14 issues in, one might think that we’d already have a great handle on what Kill or be Killed finds important, but this issue managed to surprise me with the details it chose to focus on.

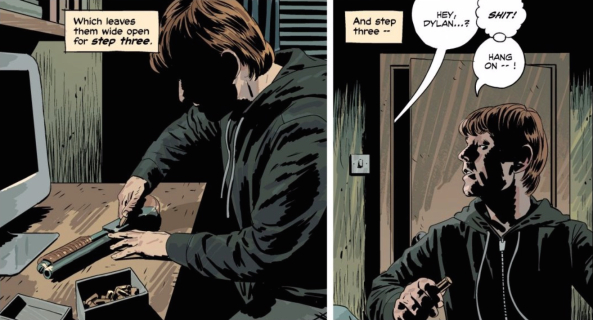

Specifically, the character of Mason. I kind of doubt that Mason is ultimately important to this story — I had completely forgotten his name before picking up this issue — but his relationship to Dylan, and more specifically, Dylan’s attitudes regarding that relationship, ends up stepping into the spotlight here in a way I might not have expected. Of course, it seems like Dylan doesn’t really expect it, either. He’s literally in the middle of explaining his plan to us when Mason interrupts his train of thought.

Just as we’re getting keyed up for Dylan’s master plan, he’s pulled back into the world of setting up “ground rules” with his roommate. It really does feel like an interruption, and writer Ed Brubaker leans into that idea, doing away with the narration (that was so abruptly cut off in the passage above) for the next two pages. It’s enough to make us almost think this really is an interruption to the story — as though it takes place outside of the diegesis that is Dylan’s narration.

Obviously, that’s absurd; Brubaker and artist Sean Phillips are showing us this conversation for a reason, and sure enough, the narration returns, showing just how Dylan’s second life is changing his everyday relationships. He tells us this is the kind of thing he’d normally just accept in order to avoid conflict, but he rejects it here, specifically mentioning his actions in dark alleys as a contrast to his normal passivity. His aggression is seeping into his normal life, and it’s almost certainly cost him a friend. It’s not yet clear if this will have any direct consequences, or if it’s just meant to illustrate Dylan’s mental state, but it’s certainly important to the story, even if we don’t fully understand how.

Of course, to Dylan, it really is just an interruption. Once it’s over, Dylan resumes his planning and carries off “Step Three” without a hitch. You know, unless the foreknowledge that this doesn’t ultimately solve his problems is a “hitch.” We can’t know if Dylan is writing this story on the lamb or from a jail cell, or just telling it to himself in the final seconds of his life, but we know that his troubles don’t die with that Russian Mobster. Maybe he continues to fight crime, as he ponders after returning home. Or maybe the Russian Mob keeps coming for him. Or maybe Mason starts to suspect something more sinister is going on with Dylan’s change of character.

Or maybe the “demon” has something to do with it.

The return of that “delusion” along with a confirmation that Dylan’s long-dead brother definitely saw the same thing points this series in a decidedly different direction that I ever anticipated. I was satisfied enough with the “it was probably a hallucination” explanation, but this reveal complicates that notion, perhaps beyond credulity. I can’t rule out some kind of extremely specific hereditary mental illness, but a literal demon might be the simpler explanation at this point.

Wow, Ryan, there’s a lot to talk about in this issue, but that final image might be the best place to start. Do you have a pet theory on that, or any further clues as to what exactly might be going on here? I’m especially curious to hear how either case influences what kind of story we think is ultimately being told here.

Ryan D: I think I’m done with pet theories after what we learned this issue, Drew! I’ve been more than certain, many times, that this demon was a hallucination, retroactively-placed means of self-sabotage, or a real malevolent entity. Whatever it turns out to be, it should hypothetically be — according to the rules of narration — the one which both raises the stakes for Dylan as a character while also fitting best thematically with what the creative team deems to be their overarching message. Does that help me figure out what’s going on now that the demon’s form is manifesting on over Kira? Nope, not at all actually, but Brubaker has been writing the twisted narration of noir for ages now, so I’ll just trust that he knows what he’s doing at this point.

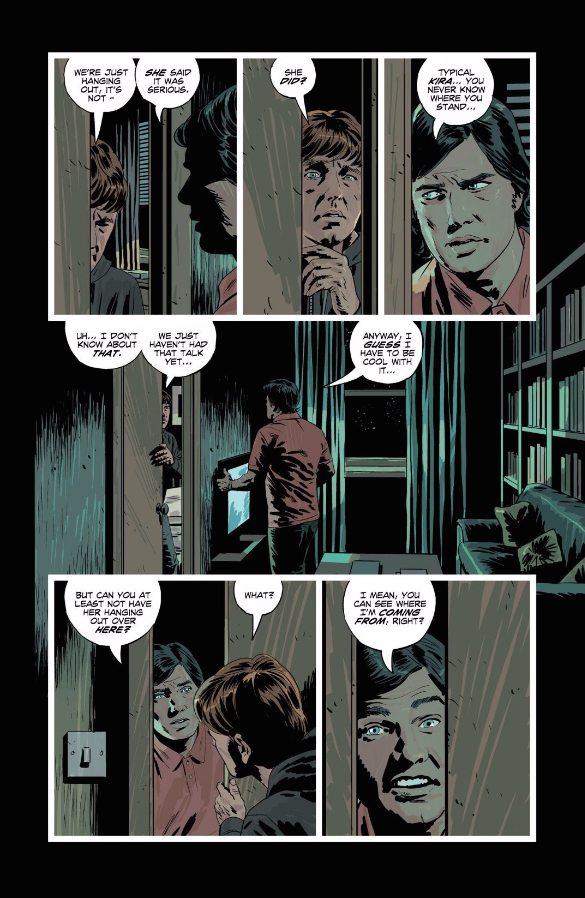

Speaking of craftsmanship at work, the Mason episode piqued my interest, too. Alongside what Drew pointed out about the larger implications on Dylan’s character development and how this interjection fits into the meta-narrative, I loved Sean Phillips’ subtle storytelling here. Phillips quickly establishes the rank between the two characters in this scene:

While Dylan seems meek and closed off within the frame of the door, Mason appears as larger than our main character, and is seen on the next page standing with his shoulders relaxed and his arms propped on his hips. This confident stance not only exposes Mason’s chest/heart but also takes up more space in the room and on the page. It’s not until Dylan starts pulling rank that we see him larger than Mason and dominating the page and panels, effectively “winning” the scene.

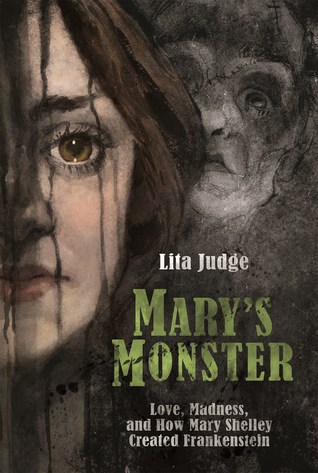

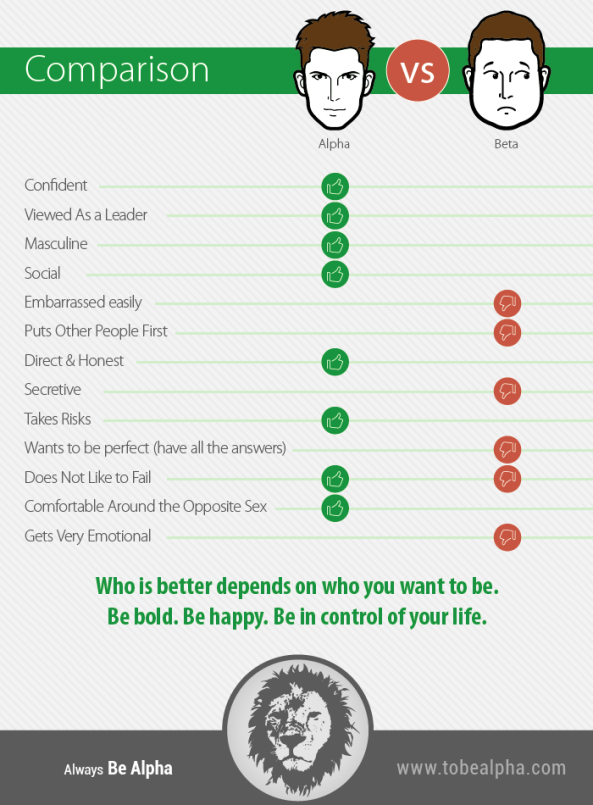

While this may seem like a win for the underdog, I see it instead as a comment on perceptions of stereotypical masculine behavior. Particularly, Men’s Rights groups like the Red Pill use the distinction beween the Alpha vs. the Beta male for their agenda. One graphical representation:

While some might see this as a reductive, pseudoscientific corruption of actual sociology used to justify a group’s actions, it’s interesting to see how Dylan’s journey from the beginning of the title, back when he was lamenting that he wasn’t “the kind of guy who could beat up three assholes on a city bus”. Dylan began as a thoughtful, emotional lad who dealt with conflict by monologuing in his bedroom, which is like, super Beta, bro. Mason, on the other hand, embodied the somewhat crass, direct, maybe-played-football male paradigm. Now that Dylan’s begun his extracurricular murdering, however, we see him shift into the more traditional prototype of masculinity and celebrate it as progress as he out-Alphas Mason. I’m interested in seeing how the title treats Dylan’s shift in behavior, and how his second life’s power fantasy continues to effect his primary life, as it will speak directly to what this comic values when it comes to contemporary masculinity.

What I’m finally sensing is Brubaker delighting in our indecision as he steers us in different directions by refusing to give us clear answer as the audience struggles to classify aspects of plot, theme, and character. Hero or villain? Alpha or Beta? Unholy intervention or schizophrenic hallucination? Kill or be Killed laughs at our need to figure out whether something is “this or that” and insistently swims in shades of grey morality and dark shadows.

For a complete list of what we’re reading, head on over to our Pull List page. Whenever possible, buy your comics from your local mom and pop comic bookstore. If you want to rock digital copies, head on over to Comixology and download issues there. There’s no need to pirate, right?

Advertisements Share this: