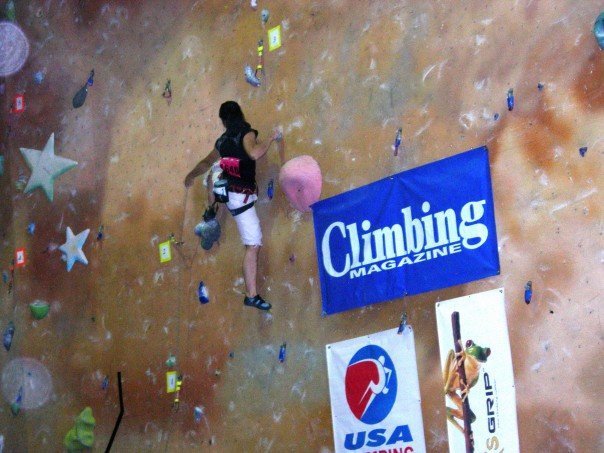

Originally published in Rock and Ice Magazine: Learning To Climb For Myself, The Hard Way.

I took a deep breath. Sweat beaded on my temples and worked through the chalk in my fingertips. Ninety minutes remained at the Doylestown Rock Gym competition in Pennsylvania. The blank spaces on my scorecard demanded urgency. I turned to my coach, Dana Seaton, for advice.

Dana stood next to me, deep in conversation with the parent of another competitor. His brows furrowed and he spoke quietly, shoulders tensed. The mom was upset. As their voices raised, Dana squared his body away from me, attempting to hide their conversation. The woman’s mouth opened, her eyebrows knitted, her face turned crimson. The more I listened, the more I realized why Dana wanted to protect me.

“I heard a girl on your team cheated at Regionals last year. My daughter doesn’t want to compete against a cheater, anyways!”

My face flushed with embarrassment.

I was the cheater.

Everyone knew it.

— –

I joined a competitive team at 13, a year after I started climbing. We met a few days a week, splitting time between indoor workouts and outdoor excursions to the local bouldering spots. I respected my coaches and admired my teammates – the majority of whom were male. Good-natured ribbing and friendly competition set the par for the course. An inner pressure grew in my mind, driven by ego and a desire to prove myself. I wanted to show that I could climb as well as the boys, and better.

As the pressure grew I became preoccupied by what other people thought of me. Climbing competitions became my source of validation. If I placed well, I would earn praise. If didn’t place well, I would disappoint. This thinking drove me through my first year of competition. I improved as a climber and stood on the podium at several local comps. As the 2004 USAC Youth Regionals approached, I knew I had a chance at qualifying for Nationals. The event represented a huge milestone for me. I wanted it more than anything.

On the day of Regionals, I walked through the doors of MetroRock South in Boston, MA. It was a few months after my fourteenth birthday. The gym hummed with excitement from a hundred youth climbers hoping to make the cut. White clouds billowed, born of nervous chalking that added to the organized chaos. I ran from problem to problem searching for the highest scoring climbs. My eyes darted through the crowd, studying the progress of the other girls. I needed to beat them. Meg Georgevits and I vied for 2 nd , the minimum place to move onto Nationals. I climbed well but so did Meg. I couldn’t tell if I had performed better than her.

As the 10-minute warning sounded I panicked. One problem remained that I had come close on but hadn’t completed. Justifications swirled; I could have done that climb. I basically did it anyways, falling on the very last move. If I missed my chance at Nationals I would let everyone down. I wanted to see happiness in my coaches’ eyes, not disappointment. My pride couldn’t allow anything less.

My eyes darted nervously. I folded my scorecard and tucked it into my shirt. The corner stuck out awkwardly, scratching against my skin. Would anyone notice? I grabbed a pen on the way to the bathroom, masked by the throngs of spectators. I committed to my decision with a single-minded intensity. In the privacy of the stall, I studied a pair of judges’ initials that had signed off on completed climbs. I tried to keep the ink steady as I carefully forged the same initials next to the climb I hadn’t done. When the competition ended, I handed my scorecard in with a beating heart. Hopefully it had been enough.

An eternity passed while results were tallied. I sat with friends, covering my nervousness with idle chatter. When the judges posted the scores, I half-expected to see – disqualified – next to my name. Instead, I placed 2nd . I hugged and high-fived my teammates, thrilled that I would get to compete in the 2004 USAC Nationals representing my gym, my team, and my home state of Rhode Island. The praise and support I received only helped to vindicate my actions. I was a good climber; everyone told me so. I deserved to move on.

When the event came a couple months later, I felt less pressure to place well. It was my first national-level competition after all. As it happened, I climbed my way to 2 nd with no need to forge anything. I beamed as I received my team jacket and trophy, assured that I deserved to be there.

I continued to compete into the 2005 season. My ego remained unchecked. Once Nationals ended, the inner pressure returned. I found myself climbing in a local event where the highest stakes were a crash pad or a pair of shoes for 1 st . The familiar haze of white chalk settled in the air over the local climbers. My muscles ached from falling off the last move of a climb I had tried multiple times. Only minutes remained in the competition. I couldn’t let people see I had failed. I snuck into the bathroom and repeated the whole process – forged initials and defensive excuses. After an hour of waiting for results, Gigi Metcalf, the head of the USAC New England Region, approached me, frowning slightly, her lips a line of troubled concern. My heart sank.

“Nina, we need to talk about one of your scores here. When did you do this climb?” She pointed to the one I hadn’t done.

“Right at the last minute,” I responded. “That was a hard one! Took me awhile.” I tried to play it off, ignoring the heat rising to my face.

“See… I would like to believe you.” Gigi said. “But we saw you fall on the last move again and again. Nobody saw you send it. And we don’t recognize the initials that are signed here.”

I stared at the scorecard in her hand, the evidence of my guilt. A lump formed in my chest and stuck in my throat.

“Nina, did you cheat?”

I couldn’t answer.

— –

After Gigi caught me, USA Climbing reviewed my competition placements from the past season. They discovered that I cheated at Regionals – the pen I wrote with had red ink, standing out against the black signatures. I had to compose and read apology letters to my coaches, teammates, parents, gym employees, and fellow competitors. I was banned from the rest of the 2005 bouldering and sport climbing season but still had to volunteer at the rope comps. USA Climbing revoked my team jacket and trophy. The climbing community, which had become my whole world, rejected me. My team splintered; some parents demanded I be kicked out of the gym. My high school boyfriend (who was part of the climbing team) broke up with me. An assistant coach whom I admired, said that going to Nationals with me had been a waste of his time.

After weeks of reflection, I recognized that relying on validation from other people made me distrust my own abilities. I became so wrapped up in climbing for everyone else that I had forgotten to climb for myself.

Over the next few weeks I read my apologies, belayed at the rope comps, and returned the jacket and trophy. I had searched for the easy way and found the hard way instead. The weight of my experience served to bury a darker part of myself that I didn’t want anymore. I was never tempted to cheat again.

Despite the trials, my need for climbing remained unchanged. Competitions still offered an arena of excitement, with the challenges of problem-solving becoming a renewed source of motivation. I realized my fear of disappointment had blinded the appreciation my community already had for me – regardless of any podium achievement.

I have nothing to prove.

I try hard for myself.

I climb because I love it.

I repeated this to myself as I walked towards the exit of the Doylestown gym. My chest hiccuped, aching with silent sobs. The outdoor breeze did nothing to cool the heat of humiliation still burning on my face. Raindrops mixed with tears that crept through my eyelashes and spilled onto my cheeks. I still cared about what others thought. Hearing Dana and the mom’s argument brought back a reality that seemed would never go away. I knew the incident would fade from people’s minds. I also knew it would stay with me for years.

Dana came to console me and, after a few minutes, we talked about the remaining time in the competition. I pulled my knees to my chest and hid my face. “I can’t do it.” I said. “Everyone looks at me weird. I don’t want to climb anymore.”

Dana gazed downwards, considering his next words.

“The past is like your wallet. You pull it out if you need something. But most of the time it just hangs out behind you. So you can either sit here and sulk,” he said, “or you can get your head out of your ass and finish what you started.”

I took a moment to sulk. My face still burned. I raised my head and uncurled my knees, staring at my scorecard. The blank space of one climb remained.

I laced my shoes and walked back inside.