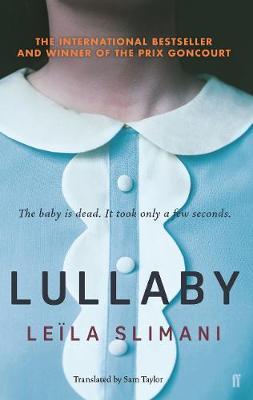

Lullaby is one of those books I genuinely wanted to love. It was flagged up a few weeks after I received it, by many of the people I follow on Twitter. A buzz had started to build and the book sat on the table next to my bed. I was putting off reading it because of the line on the cover and that opened the novel – “The baby is dead. It only took a few seconds”. I felt that a book that opened with that line might make me feel a little too uncomfortable; it might cause me to dwell on certain topics for longer than I would like to. I don’t shy away from difficult books, especially those that force me to look at subjects that spark memories.

Lullaby is one of those books I genuinely wanted to love. It was flagged up a few weeks after I received it, by many of the people I follow on Twitter. A buzz had started to build and the book sat on the table next to my bed. I was putting off reading it because of the line on the cover and that opened the novel – “The baby is dead. It only took a few seconds”. I felt that a book that opened with that line might make me feel a little too uncomfortable; it might cause me to dwell on certain topics for longer than I would like to. I don’t shy away from difficult books, especially those that force me to look at subjects that spark memories.

I decided to read this book partly to see what the fuss was about and partly because I’m currently in a phase of reading about murder that occurs due to a behavioural or mental issue. First of all, the hype for this book is warranted to some extent; the writing is tight and sparse. There is no overwriting of sentences here, Leila Slimani composes paragraphs with a deft touch and I can only assume that this skill has passed through the translator, who has aided the text by keeping the beauty of the French language intact.

Passages that look at violence are written with a tenderness, rather than with a graphic ideal in mind. Details are left out of certain scenes allowing the reader to fill in the blanks, which is one of the great skills of a good writer. An early example of this is the crime scene within the French apartment. Slimani doesn’t show us the image in pieces, there’s no need. However, when she describes the grief of the mother witnessing the aftermath of the murder, she goes into excruciating detail, connecting her more intimately with the reader.

Having said that, I can’t champion the actual plot of the novel as much as the writing. Lullaby opens strongly – a baby has been murdered and his older sister, a young child, is fighting for her life. The nanny, Louise, who was, before this moment, seemingly perfect, has attempted suicide. This short chapter does what it needs to do – it grabs the reader by the throat and forces them to look at what has occurred, while leaving out enough detail to push you into reading on.

A picture is then painted over the rest of the novel to describe the nanny, her history, the family, their interactions. For a long time it dances around the idea that this person who has been trusted with children is a Mary Poppins figure; someone practically perfect in every way. Odd hints and scenes are dropped within to show a darker side, of course. We’re shown situations that twists her mind. We see her lash out at the world. She snaps, mends herself and snaps again.

I was on board with this depiction of a mind being slowly broken by circumstance and reaction to historical situations. Like passing a car accident on a motorway, we can’t look away. We don’t just watch this unfold, we eagerly begin to lap up small details and hunt for hints at the instability of this woman. And then the book reaches the end point where everything falls rather flat. I wasn’t necessarily expecting a crescendo finale, but I wanted something. The ending appears as if an editor has torn out the final thirty pages in order to be mysterious or artistic, when what it really does is lessen the impact of what has transpired.

Of course, we could look at this ending in another way. The book was never about the nanny and her mind, it was about the family and how they let their guard down, allowed this woman to become that close. And this would have worked out well if it weren’t for the fact that we’re constantly shown the history of Louise – her childhood, her daughter, the violence of her marriage, her attempts at a normal life in a small bedsit that is painted to appear more like a prison cell, rather than a home.

I get the feeling that while the Slimani knew what words she wanted to put to the page and while she knew which topics she wanted to touch upon, ultimately she didn’t fully commit to what the actually is. It isn’t a thriller, it isn’t a literary dissection of society, the mind and family. It’s a good idea that is well written, but ultimately a little forgetful.

Advertisements Share this: