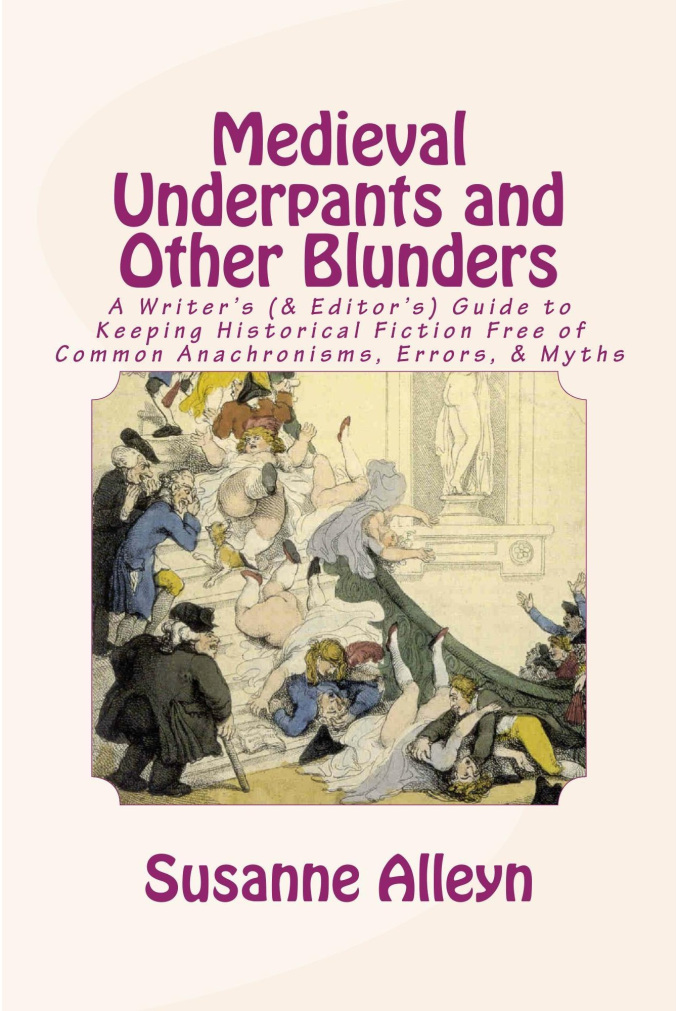

Think you can crank out a novel about the Knights Templar just because you played a few rounds of Dungeons & Dragons? Do you feel like you know the Victorian era just because you’ve read every story featuring Sherlock Holmes? Do you pepper language with “thee” and “thou” to make your characters feel elevated and self-important?

Or maybe you’re the one who watches Downton Abbey just to spot the random plastic water bottle that got left in the shot by mistake?

This book might be for you.

There are so many assumptions and foibles when it comes to history. The first rule that any writer or reader needs to understand is that the past is an alien world, and all that implies. The customs, mannerisms, social norms, expectations, politics, religions, clothes, weaponry, tactics, food, drink… it’s all different than what you know or think you know. For many who read historical fiction, that’s the entire point. That’s where it becomes escapism. To make that illusion work, the writer has to do their job and do it well. This means becoming as immersed in every aspect of the history of a place and time without sacrificing the sense of drama.

For example, if your 1920s Chicago mobster is giving directions for a hit that include an address on Kennedy Drive and executes that hit with an AK-47, the reader is probably going to throw the book against the wall and avoid that author like the plague from that point forward. I can’t take Diana Gabaldon seriously because even her basic information about swords is beyond irresponsible. Scottish claymores don’t weigh anything close to 15 lbs., and you can’t throw them end over end like a knife in a carnival act. If you can’t trust her history, how can you trust a story she’s telling across two historical periods? Ever watch Braveheart? Everyone’s wearing kilts centuries before they were commonplace in Scotland, and the princess should be all of nine years old when Wallace is executed. No reader (or viewer) should ever have to let something go just because the effort that went into creating something was substandard. Just like you wouldn’t be happy if a mechanic kicked the tires on your car and called it fixed, you expect a level of quality from a so-called professional who’s expecting you to pay with your time and hard-earned money. You expect the time and effort they put into it to be worth it to the writer as much as it is to reader. Demand better. The high tide raises all boats.

Although it comes across at times as a bit of a snarky know-it-all book, this little tome is a public service to historical fiction writers — and to their audiences. While I find that readers are generally a smart bunch, especially those who know a specific niche backwards and forwards due to the time they spend there, I’m also in that camp that finds it appalling the sheer amount of people who learn history by reading Philippa Gregory or Diana Gabaldon. That tells me that the more authors dumb things down, the more readers will dumb it down too. It becomes part of a cycle where people get lazy. Because we live in the age of the internet, people think they know everything already, and nobody is willing to look up anything to verify. That’s what this book is about. It’s not about nitpicking for the sake of nitpicking; it’s about spotlighting the common misconception that “nobody will notice” the shortcuts. The moment you think that, everyone will notice. That’s a promise.

Writing fiction is difficult. If it’s not, you’re doing it wrong, and it’ll come across your work. To achieve the best work, especially when writing historical fiction, a writer has to wear many hats: historian, archeologist, social worker, detective, linguist, costume designer, artist, architect, military strategist, weapons expert… the list just goes on and on depending on the time, place, and specific focus of the story being told. The target audience who will pick up that book will know when you bullshit your way through something, even if you aren’t aware that’s what you’re doing. The internet will not let you live it down either. Good research for a novel is like a fantastic special effect in a movie. If you do it right, it feels wonderful and natural and makes the world come alive within the story you’re creating, and nobody picks it apart to understand why it works. They just know that it works. If you half-ass it, it becomes a warning to all others, and you lose a core of would have been your loyal and adoring audience. I would go so far as to say that it works that way in fantasy settings too. Even magic has rules, and if you’re writing fantasy because you’re too lazy or intimidated to write historical fiction, you’ve already screwed up. That’s why there’s so much bad fantasy out there. There’s only one Tolkien, people.

Then again, Gregory and Gabaldon seem to be making their money on a legion of fans, and Braveheart did win an Oscar, so maybe these things completely undermine this book and this review. And maybe this review is more of a rant than a review. Whatever. I still give this book all due applause. The armchair historian and medievalist in me appreciates the effort that went into this.

4 stars