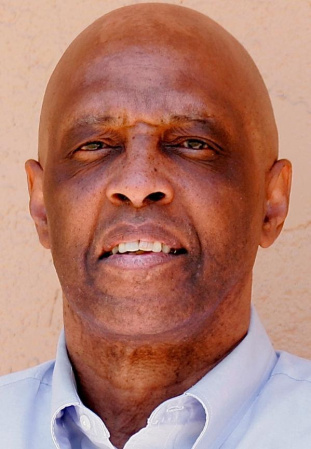

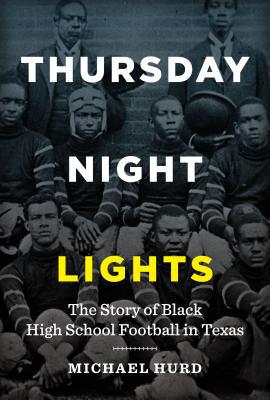

Author Chris Barton has allowed us to share his conversation with Michael Hurd, author of the new nonfiction book “Thursday Night Lights: The Story of Black High School Football in Texas”. To sign up for Chris’s newsletter and be eligible to win a copy of this fascinating book, click here!

BookPeople is proud to host Mr. Hurd this Saturday, Oct. 21st at 6 PM. We’d love to see you there! To learn more about this event click here.

Chris: The influence on and involvement in students’ lives by their coaches was one of the most striking aspects of Thursday Night Lights. Was there a particular relationship between a coach and his player – or players – that was especially meaningful or moving to you?

Chris: The influence on and involvement in students’ lives by their coaches was one of the most striking aspects of Thursday Night Lights. Was there a particular relationship between a coach and his player – or players – that was especially meaningful or moving to you?

Michael: That’s a great observation. What immediately comes to mind is Houston Wheatley’s Frank Walker. In the book, his daughter, Frances, talks about how her dad was so committed to building the program and taking care of his players that it confused the family’s budget.

Out of his own pocket, Coach Walker would buy needed practice equipment, maybe provide a meal now and then, and for his graduating seniors going off to college, he’d purchase their bus tickets, clothing, and give them some pocket money.

But, I doubt he was the only coach in the PVIL who did those kinds of things for his players. There was a real symbiotic relationship between the players and coaches at the PVIL schools and those relationships extended well off the field as nurturing experiences. Many of the coaches were father figures for boys who may not have had a male parenting figure at home, and even some who did.

In regard to that, my favorite quote in the book is from Joe Washington, Sr. who coached in Bay City and Port Arthur. He talks about the trust that parents had in him, and black coaches in general, to discipline and essentially raise their sons. He said the mommas would tell him to take their son and do what they needed to do, “just don’t kill him!”

Chris: Your interview subjects were frank about the bittersweetness of integration as it affected black high school football programs and the people in those programs. How did what you learned from them square with your own recollections about integration and the waning days of segregation?

Michael: That was one of the things that I really enjoyed about researching and writing the book. A lot of my interviews turned into old home week discussions, reflecting on the Sixties and what that was like for black people as segregation slowly eased into integration. One day there were all these places – theaters, restaurants, neighborhoods – that before, we couldn’t go here, we couldn’t go there, couldn’t do this or that, then the next day, no problem, more or less. So I talked about those kinds of things with a lot of my interview subjects, especially the Houston guys, and those conversations brought back a lot of memories for me. An example: I had always gone to segregated schools, elementary and high school, and graduated in the spring of 1967. Then, in the fall of that year, black and white schools played against each other for the first time. So, when I went back for homecoming it had a totally different feel. We were playing at a different stadium and against a white team!

- More