There is a fundamental principle of transmission of information. In the newspaper business, they say ‘Don’t bury the lead’, meaning make the main story upfront and immediate … then fill in the details. So here we go.

YOU LEARN BETTER IF YOU PRACTISE A VARIETY OF THINGS ALL MIXED UP THAN IF YOU DO REPETITIVE PRACTICE OF ONE TYPE OVER AND OVER AGAIN.

There, done. Now the detail.

Automaticity

Have you ever driven home from work or from the shops and when you arrive home,  had the odd sensation that you don’t remember a single moment of the journey? I have that often when I’m on the home stretch of the journey from my school to my home, 25 km away. It includes a stretch of motorway with tollgates at either end, and I often can’t remember joining or leaving the motorway. This does not mean, of course, that I was driving in a complete daze of oblivion. It means rather that the process of driving has become so automatic that it is drilled deep down into my subconscious and can be carried out without any conscious awareness. In Daniel Kahneman’s terms, I suppose, I’m thinking fast, and remembering slow.

had the odd sensation that you don’t remember a single moment of the journey? I have that often when I’m on the home stretch of the journey from my school to my home, 25 km away. It includes a stretch of motorway with tollgates at either end, and I often can’t remember joining or leaving the motorway. This does not mean, of course, that I was driving in a complete daze of oblivion. It means rather that the process of driving has become so automatic that it is drilled deep down into my subconscious and can be carried out without any conscious awareness. In Daniel Kahneman’s terms, I suppose, I’m thinking fast, and remembering slow.

So what makes the process of driving – the process of controlling a 1-tonne, lethal mass of metal through a complex succession of steering, accelerating, braking, judging distances, coordinating both feet and hands at the same time and scanning the road for potential hazards in front of me and behind with mirrors – so automatic?

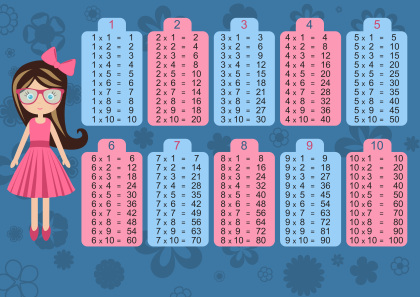

Early learned automaticity

Let’s liken this to something else more familiar and – for most people – just as automatic, though usually less dangerous: learning your multiplication tables (times tables, as they were called when I were a lad).  When I learned my times tables, we all used to chant together: one times three is three; two times three is six; three times three is nine… etc. In doing so we slowly learnt the basic building blocks of knowledge that we could manipulate later when we needed. But do you remember the panic of the spot tests where the teacher (Mr Garner, in my case) would rattle out random questions to quivering pupils: What’s seven times three? What’s six times nine? What’s [my personal nemesis] eleven times twelve?

When I learned my times tables, we all used to chant together: one times three is three; two times three is six; three times three is nine… etc. In doing so we slowly learnt the basic building blocks of knowledge that we could manipulate later when we needed. But do you remember the panic of the spot tests where the teacher (Mr Garner, in my case) would rattle out random questions to quivering pupils: What’s seven times three? What’s six times nine? What’s [my personal nemesis] eleven times twelve?

This stage of mixing up the times tables and throwing us random and unpredictable questions was what really helped fix the answers in our heads. You mix it up, you deal with the unpredictable and you fix those answers deep in your subconscious. That’s interleaving.

Learning is more efficient and longer-lasting if it is interleaved – mixed up – rather than done in blocked or massed practice. I may already have said that.

In real life, you never know if you’re going to get a curve ball or a fast ball or a straight ball. Talking of which, the same applies to exactly these motor skills. California Polytechnic State University baseball team did an experiment with their hitters. They  divided them into two groups: one which practised curve ball after curve ball after curve ball, etc. and then fast ball after fast ball after fast ball, and so on. The other group were taught what a curve ball, fast ball and straight ball were like and then practised hitting whatever was randomly thrown (literally) at them. At the end of the training period, they tested which players were able to deal better with a random selection of pitches, just like they might get in a real game. The interleaved group who trained with a random selection hit the others, so to speak, out of the park. Blocked or massed practice, it was proved once again, leads to momentary mastery, and then little or none at all. Tarnation!

divided them into two groups: one which practised curve ball after curve ball after curve ball, etc. and then fast ball after fast ball after fast ball, and so on. The other group were taught what a curve ball, fast ball and straight ball were like and then practised hitting whatever was randomly thrown (literally) at them. At the end of the training period, they tested which players were able to deal better with a random selection of pitches, just like they might get in a real game. The interleaved group who trained with a random selection hit the others, so to speak, out of the park. Blocked or massed practice, it was proved once again, leads to momentary mastery, and then little or none at all. Tarnation!

Are you a mixer or a blocker?

Back to driving. Fortunately, the only way to learn to drive is to learn to use accelerator, brake, clutch, gear stick, mirrors and wheel ALL AT THE SAME TIME OR MIXED UP TOGETHER. You’re obliged to interleave if you actually want to get from A to B. And that is why we all (or at least nearly all) acquire this complex set of skills quickly, intuitively, deeply and lastingly. No instructor is ever going to spend a whole lesson teaching you how to put your car into first gear and then back into neutral and then into first gear and then back into neutral without ever engaging with the road. The only sane way is to mix it up and interleave all the necessary skills. We become so proficient so quickly that we soon don’t even notice a 30-minute drive home. (Unless we get stuck in traffic, in which case it’s the end of civilisation as we know it.) Interleaving is key in leading us to such mastery.

So, here’s a set of questions before the next blog post which will bring us teachers (or self-studiers) back to the real world (or at least the classroom):

Questions

I start here with interleaving, as – while it may be the most valuable and easily applied technique for the classroom, it is also, according to studies, the one that meets with the most resistance from students. Even when presented with the evidence that the interleaving group did better than the blocked practice group, subjects often deny any positive influence of interleaving.

(And the reasons for this are almost as interesting as how the technique itself can boost your students’ learning. But that, as tertiary detail, will come later. Basketball will play a key role. Yes, you read right.)

So – what does this all imply for making our teaching or learning more effective?

Well, that will have to come in the next post: some evidence-based suggestions, challenges and … anger management!

Share this: