When I was pregnant with my daughter, I did what a lot of pregnant literature professors do—look for enough books to fill a library for their future genius. In my case, along with my own childhood favorites (Russell and Lillian Hoban’s Frances books, Eric Carle’s The Very Hungry Caterpillar, Dr. Seuss, my favorite fairy tale “The Twelve Dancing Princesses”), I wanted to get books where the characters would look like my child. But this was not so simple. In addition to the fact that many picture books have animals rather than people as characters, most of the people characters are white. Those that aren’t are from a single, identifiable racial group. My child would be mixed race.

Tony Bradman and Eileen Browne’s books about Jo show a confident, happy, mixed race child–but on book covers, she is all alone.

I went searching anyway, and found a few—not many. I commented on these in an article I wrote, “Why are People Different? Multiracial Families in Picture Books and the Dialogue of Difference” (Lion and the Unicorn 25.3, September 2001: 412-426), You can read the article yourself (it isn’t too tedious) but the Ladybird version of the article is that I was disappointed in most of the books I did find. The picture books I looked at then emphasized “difference and a physical space between the racially different parents” (423). During that same year, Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe wrote, in her essay “Re-Membering ‘Race’: On Gender, ‘Mixed Race’ and Family in the English-African Diaspora,” that it was important that young people had representations they could look to because “neither the exclusionary discourse of White Englishness nor the inclusive discourse of the Black English-African diaspora completely represents their everyday lived realities” (50). Of course, no one book can carry the burden of completely accurately representing the lived realities of any actual human, and not all the books were all bad. I was especially fond of Tony Bradman’s and Eileen Browne’s picture books about a little girl named Jo (Through My Window, In a Minute, Wait and See). And none of us in my family are badgers, but we still enjoyed singing the little songs Russell Hoban’s Frances made up—so books that are not about “race” can still raise a sense of recognition in a reader.

But I did wonder (and worry) what my daughter would have to read as she got older, and books stopped having visual representation of mixed race families—especially as in many of the picture books, the visual representation is all the representation that existed, the text itself could have been about—well, about badgers. Would my daughter see people who looked like her when books left the character’s description to the imagination? Or would she see the “normal” (that is, white) hero or heroine as most readers, no matter what their racial background, do? And would there be any mixed race families for her to read about?

It turns out that the generation who grew up at the same time as my daughter expected to find multiracial families in books, and to some extent have got them. I think that a recent rise in the number of YA and tween books with multiracial families/biracial characters has been advanced by the brilliant crop of BAME British writers who have begun scooping up prizes right and left. While white Britons (and Americans) may or may not know someone who is of mixed racial heritage, most BAME people know at least someone—if they aren’t part of a multiracial family themselves. Things have changed in the decade and a half since I wrote my article.

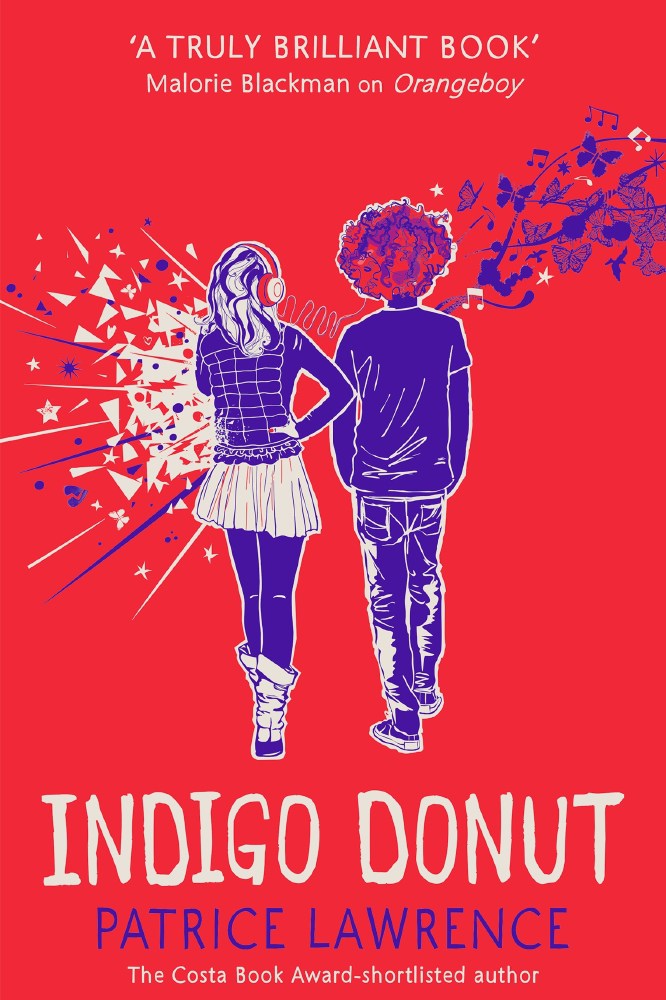

Both Brahmachari’s Artichoke Hearts and Lawrence’s Indigo Donut show the multiracial couples physically linked.

First, one of the things I discussed in my article was the fact that racially different people were often physically separated in illustrations, even when they had a textually-stated reason to be close (such as being married!). Book covers are different from picture books, of course—YA authors do not (usually) have any say at all about who does their covers. Nonetheless, I see the covers of books like Sita Brahmachari’s Artichoke Hearts (Macmillan 2011) and Patrice Lawrence’s Indigo Donut (Hodder 2017) to be quite positive advances over the books available to my daughter as a child. Mira, the Indian- and English-heritage protagonist of Artichoke Hearts, and Bailey, the Afro-Caribbean- and English-heritage main character of Indigo Donut, are not alone on their respective covers—as, for example, Jo is on the cover of all the Bradman and Browne books. As befits books for the 11+ age group, both Mira and Bailey are depicted with their romantic interests. But unlike the pictures of married couples in the picture books I reviewed in 2001, the young lovers on these covers are linked physically (as they are in the books). If you think that this is unremarkable, consider that Sarah Garland’s lovely Billy and Belle (Reinhardt 1992) faced difficulties getting published because the parents, one Black and one white, were shown in bed together. Garland was told that many countries would censor the book unless she removed the scene. (She didn’t, and it wasn’t published at the time in South Africa, among other places.)

Garland’s Billy and Belle was controversial because the parents actually slept in the same bed–shock horror!

Second, and perhaps more important, the books being published now no longer emphasize the idea of difference in a negative way. As with any real child of a biracial marriage, the fact of being “mixed” only comes up occasionally. Mira’s brother has different colored eyes than her, and her writing teacher describes her as having a “dual history name” (7), but it isn’t something that comes up every day. Even when Mira goes to India in the sequel, Jasmine Skies, the emphasis is on her learning about her Indian heritage, not about her being “mixed”. Alex Wheatle’s Crongton Knights (Atom 2016) announces part of the main character’s mixed heritage in the opening sentence: “My mum told me I was named after her Scottish granddad, Danny McKay” (1); McKay and his brother are also named after famous people of African heritage, Medgar Evers and Robert Nesta Marley. But both McKay and Mira are part of their neighborhoods and families, not individuals set apart and “different”. It is true that Lawrence’s Bailey faces teasing over his ginger afro, but he has learned to deal with it. Rather than keep it short, he grows his hair as big as it will grow, telling Indigo that to cut it would be “telling people like Saskia they’re right” (78) to tease him. Difference is not a problem to be solved, but one of many aspects to be celebrated. The young characters in recent books for children may be mixed—but they are far from being mixed up.

Alex Wheatle’s Crongton Knights announces the multiracial heritage of McKay from the opening sentence.

Advertisements Share this: