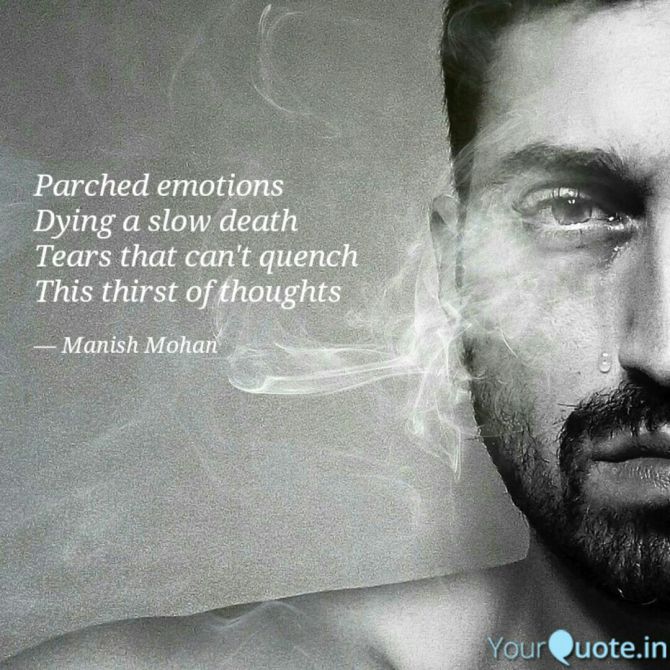

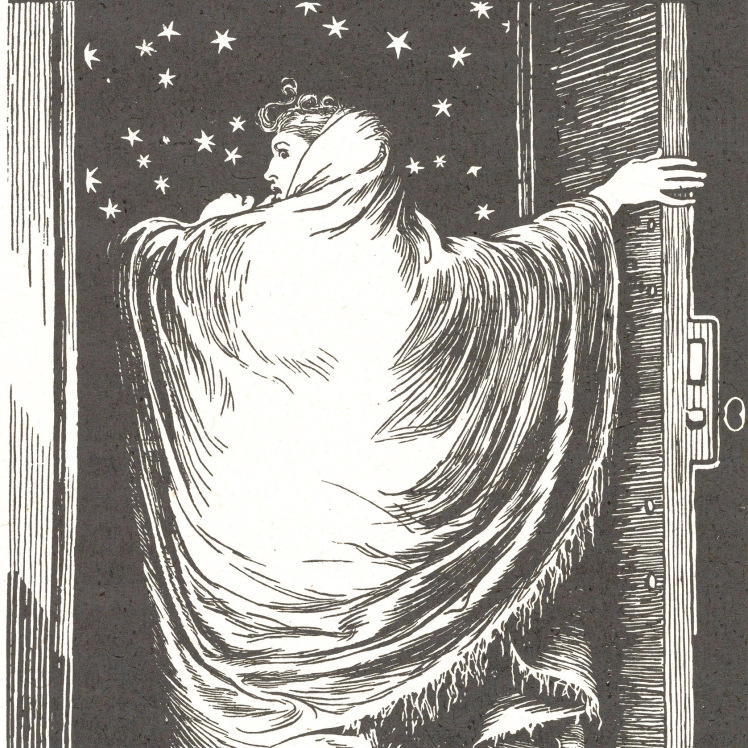

The Woman in White, illustration by Frederick Walker, 1871

The Woman in White, illustration by Frederick Walker, 1871

The mystery genre as we know it today began with the work of three writers in the early and middle decades of the nineteenth century. A line can be drawn from Thomas De Quincey (1785-1859) to Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) to Wilkie Collins (1824-1889), from them to Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), and from Doyle to all of the major mystery writers that came after.

De Quincy was born into a prosperous Manchester mercantile family in 1785. Upon the death of his father, control of his education and inheritance was entrusted to several guardians, who saw that he was furnished with a classical education. By the age of fifteen he had distinguished himself as a student at King Edward’s School in Bath. “That boy,” said one of the dons, “could harangue an Athenian mob better than you or I could address an English one.” De Quincey was ready for higher education and hoped to go on to Oxford. In this ambition his guardians prevaricated, postponed, and generally stymied him. They sent him to continue his preparatory education at Manchester Grammar School where he was miserable. By nature he was a sensitive and depressed young man. De Quincey resolved to run away from school and his guardians, which he did, just before his seventeenth birthday, relying on what little money he had in his possession, or could borrow, to make his way across the country. When this money ran out he took odd jobs to survive and could often afford only one small meal per day.

Eventually, De Quincey made his way to London. He was homeless at first, sleeping in the rough, unable to appeal to family acquaintances, for fear that his guardians would find him. He was given occasional crusts of bread by a man who took pity on him. With the onset of winter, the same man allowed him to stay in an unused house on Greek Street near Soho Square. This house was large, empty of furniture, and infested with rats. A neglected young girl also lived in the house, and she and De Quincey huddled together for warmth during the cold nights. De Quincey’s benefactor was a lawyer of dubious character and practices: he moved around frequently and, when present, regarded anyone who appeared at the door with suspicion.

During the day, De Quincey sat in parks or on doorsteps, slowly wasting away from hunger and malnutrition. He got along amiably with the prostitutes in the area, which was, at the time, London’s red light district. They protected him from the watchmen. One of these prostitutes, a fifteen year old girl named Ann, became his close friend and probably the love of his life. They spent as much time as they could walking the streets or sitting in places of shelter together. Ann was kind to De Quincey and tried to care for him. On one occasion, when he came near fainting from hunger, Ann spent her own meager resources to buy a cup of spiced wine to revive him. She told De Quincey about her past. She had been treated unjustly and he suggested that she might find restitution if she presented her case to a magistrate. He offered to help “avenge her on the brutal ruffian who had plundered her little property,” but she was hesitant.

De Quincey was in desperate need of money, for himself, and now for Ann. He appealed to a Jewish moneylender who agreed to advance him a large sum on the condition that De Quincey’s school friend, a young earl, stand as guarantor for the loan. De Quincey needed to travel to Eton to enlist the help of his friend. He had fortunately just received ten pounds from a family acquaintance. He gave a significant amount of this money to Ann, and used the rest to further his borrowing scheme.

Ann walked with De Quincey to Piccadilly, where he would catch the mail coach to Eton. As they sat together in a nearby square, De Quincey felt hopeful about his prospects and assured her of his intention to share whatever funds he was able to acquire with her. He told her he “would never forsake her as soon as [he] had power to protect her.” Ann was nevertheless miserable. She hugged him and cried as they said goodbye. De Quincey expected his trip to take around a week, and so he made plans to meet Ann again when he returned. She agreed to wait for him at the bottom of Great Titchfield Street, which was their “customary haven,” every night at six o’clock in the evening, beginning five days after his departure. Confident in this plan—after all, they had found each other every day for weeks without any more elaborate arrangements—De Quincey did not think to ask Ann her family name or address.

He set off on the journey to Eton, nearly falling from his place on top of the mail carriage due to weakness and exhaustion. Arriving at last, he succeeded in finding his friend the Earl. Though he sat down with his friend to a lavish breakfast, better than any meal he had eaten for months, De Quincey found that he was hardly able to keep food down after so long without. His friend agreed to partially guarantee the loan, a compromise that the moneylender later rejected, and De Quincey returned to London earlier than expected, after only three days. He waited for Ann at their rendezvous point on Great Titchfield Street. When she did not appear after several days, he made inquiries about her and tried to trace her based on the vague information he had, such as the street (but not the house) where she lived. He could find no trace of her. It was as though she had disappeared.

De Quincey left London soon after, the loan having fallen through. Before departing, he gave his forwarding address to an acquaintance who had also known Ann. For a long time, he still hoped he might hear from her and find her again. He never did.

After attending Worcester College, Oxford, De Quincey moved to Grasmere in the Lake District, where he sought out the Lake Poets, Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. He had read their Lyrical Ballads while still a student at King Edward’s School and the poems had made a deep impression upon him. De Quincey quickly became a member of their circle; they mentored him, and he later contributed greatly to their reputations with a series of essays on their work. He married during this period, eventually fathering eight children, and lived for ten years at Dove Cottage, where Wordsworth had written his most famous poems.

By the late 1810s De Quincey had become a professional essayist and journalist in his own right. He was hired in 1818 as editor of The Westmorland Gazette, a Tory journal published in the Lake District. Like Coleridge, Wordsworth, the poet laureate Robert Southey, and other members of his circle, De Quincey was an avowed conservative. In The Guardian, James Purdon writes that De Quincey held, “reactionary views on the Peterloo massacre and the Sepoy rebellion, on Catholic emancipation and the enfranchisement of the common people.” In personal correspondence, De Quincey “reserved ‘Jacobin’ as his highest term of opprobrium.” Purdon calls him, “a fascist avant la letter.” Hardly. He was, like Coleridge, a traditionalist and Anglican High Tory. Purdon quips, “Champagne socialists are so common as to be unremarkable; De Quincey was a laudanum Tory.” Laudanum is a solution of opium dissolved in alcohol. This is an allusion to the circumstance with which De Quincey is most commonly associated: his lifelong dependence on the drug.

Portrait of Thomas de Quincey by Sir John Watson-Gordon, undated (before 1864)

Portrait of Thomas de Quincey by Sir John Watson-Gordon, undated (before 1864)

Although he lived to the age of seventy-four, De Quincey never physically recovered from the period of sustained, border-line starvation that he had suffered in London during his teenage years. His stomach had atrophied to the extent that he could hardly eat without being sick and recurring pain in his abdomen made it difficult to lie down. These problems were obviously exacerbated by the laudanum he began taking to treat them when he was nineteen years old.

In 1820 De Quincey published Confessions of an English Opium Eater which made him instantly famous—or infamous. The book detailed his ongoing and increasingly debilitating use of opium, being in part autobiography, in part a dispassionate record of self-medication and addiction, and in part a feat of remarkable self-analysis (De Quincey coined the term “subconscious” mind).

The Confessions called attention to the worrisome side effects of a drug that was sold over the counter by druggists and grocers at the time. It also made opium use into a romantic literary trope, popular with the Sensation and Decadent writers of the later nineteenth century. De Quincey’s descriptions of the effect of opium on his dreams suggested recreational uses for the drug. He had been susceptible to unusually vivid dreams and nightmares even before he began taking it. Under the influence of laudanum his dreams became even more vivid and intense. Time seemed to warp. He had visions of a universe of beauty and horror. He suffered nightmares that felt as though they lasted for years. He described one unsettling dream in which, “upon the rocking waters of the ocean [a] human face began to appear; the sea appeared paved with innumerable faces upturned to the heavens—faces imploring, wrathful, despairing, surged upwards by thousands, by myriads, by generations, by centuries: my agitation was infinite; my mind tossed and surged with the ocean.” His dreams began to reflect the Oriental aesthetic that he associated with the drug. He wrote, in language redolent of Coleridge’s Kubla Khan,

I ran into pagodas, and was fixed for centuries at the summit or in secret rooms: I was the idol; I was the priest; I was worshipped; I was sacrificed. I fled from the wrath of Brama through all the forests of Asia: Vishnu hated me: Seeva laid wait for me. I came suddenly upon Isis and Osiris: I had done a deed, they said, which the ibis and the crocodile trembled at. I was buried for a thousand years in stone coffins, with mummies and sphinxes, in narrow chambers at the heart of eternal pyramids. I was kissed, with cancerous kisses, by crocodiles; and laid, confounded with all unutterable slimy things, amongst reeds and Nilotic mud.

Mystical and outré passages like these have always been the most popular part of the Confessions, which is otherwise a restrained and profoundly humane book. De Quincey emerged from the minor scandal that it provoked with a reputation as a writer of dark sensibilities. This was confirmed in 1827 when he published a piece of ink-black satire entitled, “On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts,” in Blackwood’s Magazine. It was this essay probably more than any other that inspired later writers of mystery fiction.

“On Murder” purports to be a lecture given to a gentleman’s club whose members are connoisseurs of death. They appreciate killings that conform to Aristotle’s theory of catharsis in drama. “The final purpose of murder,” the lecturer says, “is precisely the same as that of tragedy in Aristotle’s account of it; viz. ‘to cleanse the heart by means of pity and terror.'” De Quincey wrote at length about the Ratcliffe Highway murders which occurred in Wapping, East London, in December of 1811. A sailor named John Williams slaughtered Timothy Marr, a shopkeeper, Marr’s wife, infant son, apprentice, and servant girl in their home at night. A week later he did the same to John Williamson, proprietor of the King’s Arms tavern, Williamson’s wife, and servant. Williams was arrested for the crimes and hanged himself while in police custody.

De Quincey examined the details of these murders, calling attention to crime scene investigation and the identification of clues, themes crucial to the later development of the detective genre.

The fictional Society of Connoisseurs in Murder represents a foreshadowing of the modern mystery and detective genre, but the creation of that genre was the work of another author: Edgar Allan Poe.

Poe’s character C. Auguste Dupin, a clear-thinking, puzzle-solving investigator even before the word “detective” came into common use, was the model for later characters in the genre. Dupin is the prototype of the gentleman detective: a scholar from a once wealthy family, now fallen on hard times, who conducts investigations, not as a professional, but with varied motives and in conjunction with the anonymous narrator of the tales in which he appears. Dupin is famous for his method, which Poe dubbed “ratiocination.” He is a close observer of details and makes inferences through extreme rational and logical thinking. Dupin uses these skills to put himself in the minds of criminals, solving crimes by thinking from the their point of view.

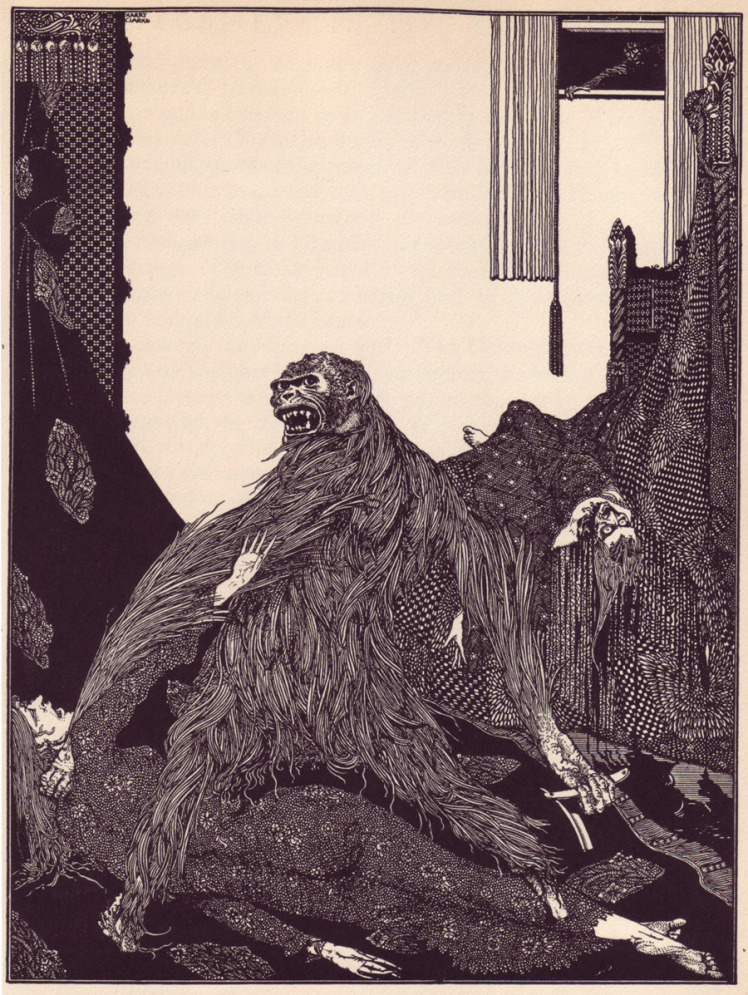

The first story in which Dupin appears, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” was published in 1841. Dupin and his friend the narrator live together in Paris, and they become interested in newspaper accounts of the mysterious and gruesome murder of two women. When a former acquaintance of Dupin is arrested for the crime on only circumstantial evidence, Dupin steps forward to help. The clues have the police baffled: one body in a chimney and one outside the house, a murder scene in a locked room, tufts of non-human hair, and witness reports of two voices—one speaking an unintelligible language. Dupin infers from the super-human agility and strength of the murderer, and the tufts of hair, that the culprit is an orangutan. He proves this by tracking down the sailor who controls the beast.

The Murders in the Rue Morgue, illustration by Harry Clarke, 1923

The Murders in the Rue Morgue, illustration by Harry Clarke, 1923

Poe followed “Rue Morgue” with a second Dupin story a year later, “The Mystery of Marie Rogêt.” This complex tale was based on the real-life murder of Mary Cecilia Rogers in New York City in 1838 and represents an attempt by Poe to solve the case. The third and final story in which Dupin is featured, “The Purloined Letter,” was published in 1844. Here the police seek Dupin’s help on a case where a Minister “D–” is blackmailing a woman with a revealing letter that “D–” has stolen. The police assume that “D–” must have the letter readily accessible, and they have thoroughly searched every potential hiding place in the hotel rooms where he is staying without success. A month later, after a huge reward is offered for the letter, the police return to visit Dupin, who produces the letter. He explains to the narrator that the police underestimated their opponent, who knew their methods and instead left the letter disguised in plain sight. Dupin, recognizing the letter even with its external alterations, arranged a distraction, took it, and left a decoy in its place. Poe called the story, “perhaps the best of my tales of ratiocination.”

The Dupin stories were the direct model for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories. Holmes and Dupin use the same method of deductive and inferential reasoning to connect clues. Holmes, like Dupin, is a gentleman amateur. Holmes, like Dupin, is assisted by a friend and fellow lodger, Doctor Watson, who narrates the stories. In the first novel in which Holmes appears, A Study in Scarlet, Watson compares his method to that of Dupin. Holmes balks, “In my opinion, Dupin was a very inferior fellow…He had some analytical genius, no doubt; but he was by no means such a phenomenon as Poe appears to imagine.” But Sir Arthur himself was well aware of the debt that he owed to Poe. “Each is a root from which a whole literature has developed,” he said of the Dupin stories. “Where was the detective story until Poe breathed the breath of life into it?”

There is no doubt that Poe was influenced by De Quincey in the broadest sense. He read the English magazines in which De Quincey was published and expressed admiration for the Confessions. In a piece of humor that Poe composed for the American Museum in December of 1838, entitled, “How to Write a Blackwood’s Article,” he noted, “Then we have the Confessions of an Opium Eater—fine, very fine!—glorious imagination—acute speculation—plenty of fire and fury, and a good spicing of the decidedly unintelligible.”

In at least one instance Poe was directly inspired by De Quincey. Poe’s short story “The Masque of the Red Death” is based on an episode from De Quincey’s novel Klosterheim, or the Masque. In her 1937 thesis, The Influence of Thomas De Quincey on Edgar Allan Poe, Ruth Kelly explains,

The situation from Klosterheim which Poe borrowed for “The Masque of the Red Death” is a masqued ball found in Chapters XIV, XV, and XVI. A mysterious masked marauder has been bringing destruction and death of a bloody nature throughout the country. It has been impossible to apprehend him, and the country is stricken with fear. The prince consequently barricades the castle during a great masqued ball to which he has issued twelve hundred invitations. A challenge of defiance has been hurled at the “Masque,” as the invader is called. Feeling runs high. Midnight approaches. A whisper begins to circulate that an alien presence is in the room. The whisper grows into a buzz. The music ceases abruptly. The order to seize him is given. The “Masque” discloses his identity to the prince who cries out and falls full length upon the ground bereft of consciousness. All rush toward the “Masque” in order to seize him, but in the confusion he disappears.

Poe built upon this premise, and transformed it, making the masked figure an allegory for plague in his own story. But it is clear that he read De Quincey closely and borrowed from him. In turn, Wilkie Collins read, and borrowed from, both of them. If Poe wrote the first detective stories, Wilkie Collins wrote the first modern mystery novels. Collins drew on the earlier gothic tradition but also on the new literary strands being teased out of that tradition by De Quincey and Poe.

In Collins’s 1859 novel, The Woman in White, a young artist, Walter Hartright, takes a position as drawing master for two young ladies, half-sisters, who live with their uncle at a manor house in Cumberland. One night before he leaves London to begin his employment, he encounters a distressed woman dressed entirely in white and helps her; later he learns that she escaped from an insane asylum. In Cumberland, Walter and his student, Laura Fairlie, fall in love. She bears an uncanny resemblance to the woman in white, whose name is Anne Catherick. However, Laura is engaged to another man, Sir Percival Glyde, and marries him. When the couple returns from the honeymoon, Laura’s half-sister Marian discovers that Sir Percival is in financial trouble. Since Laura has refused to sign over her marriage settlement, Glyde and his friend, Count Fosco, are planning to take Laura’s money by other means.

At the same time, the terminally ill Anne promises to share a secret with Laura that could ruin Glyde. Before she can do so, Fosco and Glyde carry out their plan, switching the identities of Laura and Anne. Laura is drugged and sent to the asylum, and Anne dies and is buried as Laura—leaving Laura’s money to Glyde. Fortunately, Marian finds and rescues Laura. They live in poverty in London with Walter until, at last, they discover Glyde’s secret and find a way to re-establish Laura’s identity, restoring their fortunes.

Collins’s 1868 novel The Moonstone concerns the theft of a large diamond that a British officer has brought from India and bequeathed to his niece, Rachel. The diamond is taken from Rachel’s room on the evening of her birthday, after she wore it to a party. Suspects abound: three Indian jugglers are in the vicinity; a maid, Rosanna Spearman, acts suspiciously; Rachel refuses to let the police search her room and spurns the man with whom she was in love, Franklin Blake.

During the following year, Blake leaves England. Rachel accepts the proposal of another man who was at the party, the philanthropist Godfrey Ablewhite, but later breaks the engagement. When Blake returns, he discovers that Rosanna was in love with him. She found stains on his clothes from the wet paint on Rachel’s door and tried to cover for his assumed crime, eventually killing herself in despair. He then confronts Rachel, who tells him that she saw him take the stone. Blake is entirely confused, but with the help of a doctor’s assistant, and a probing, clever police detective, Sergeant Cuff, he pieces together that he had been drugged with opium on the night of the robbery. In a trance, Blake took the Moonstone from Rachel’s room to protect it, with no memory of the event, and no memory of where he put it.

Franklin and Rachel learn that the stone is in a bank, pledged to a moneylender. They watch the bank to see who will redeem the diamond, and follow this line of investigation to the discovery of Godfrey Ablewhite’s body. He has been murdered and the stone stolen again. They realize that Godfrey, on the brink of financial ruin, took the diamond from the drugged and sleepwalking Blake on the night it disappeared. Godfrey was murdered by the three Indians—in fact Brahmin priests in disguise—who return the stone to its rightful place on the statue of a moon god in India.

“He opened the bedroom door, and went out,” illustration of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, by John Sloan, 1908

“He opened the bedroom door, and went out,” illustration of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone, by John Sloan, 1908

The influence of Poe on Collins is subtle but pervasive. In a review of Collins’s novel After Dark, George Eliot made a connection between the two authors, writing, “Edgar Poe’s tales were an effort of genius to reconcile the two tendencies—to appal the imagination yet satisfy the intellect, and Mr. Wilkie Collins in this respect often follows in Poe’s tracks.” A.B. Emrys identifies Collins as,

the bridging figure between Poe and Conan Doyle, but not because of Sergeant Cuff. Not only did Collins reprise plot from Poe multiple times but the influence of Poe’s prose monologues is a key factor in Collins’s successful development of the casebook form. The vivid voices of The Woman in White and The Moonstone are central to the continued popularity of these novels and their being ranked as Collins’s best works, and their dramatic monologues are built on those of Poe’s criminals.

The influence of De Quincey is more specific. The plot twist involving opium in The Moonstone hinges upon the Confessions. “There,” the doctor’s assistant tells Blake, handing him a book, “are the far-famed Confessions of an English Opium Eater! Take the book away with you and read it.” Episodes from De Quincey’s memoir, creatively interpreted by Collins, provide an explanation for the goings on in The Moonstone.

In 1887 Doyle published A Study in Scarlet. He would go on to write a total of four novels and fifty-six short stories featuring Sherlock Holmes over a period ending in 1927. Throughout this canon of works, references, not just to Poe, but to De Quincey and Collins, appear. Doyle seems to have been inspired by his reading of De Quincey to give Holmes a drug habit. In “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Watson notices that Holmes has “risen out of his drug-created dreams,” a concept taken straight from the Confessions, “and was hot upon the scent of some new problem.” Watson, as a disapproving physician, describes another character’s addiction to opium in “The Man With the Twisted Lip.” Here, the doctor observes, “The habit grew upon him, as I understand, from some foolish freak when he was at college; for having read De Quincey’s description of his dreams and sensations, he had drenched his tobacco with laudanum to produce the same results.”

Likewise, plot elements from the novels of Wilkie Collins echo through the Holmes canon. As Charles Rzepka notes, “The plundered Moonstone inspired Doyle’s choice of the Agra treasure as incentive to crime in the Holmes novella, The Sign of Four, where the three Brahmins that Collins set in pursuit of the gem reappear as three Muslim and Sikh conspirators who seize the treasure during the height of the Mutiny.” Doyle had already written an homage to The Moonstone: his early novel, The Mystery of Cloomber. In that book three vengeful Buddhist priests take the place of the three Brahmins.

The Sherlock Holmes series was the wellspring of the whole modern mystery genre. But it too had its source in earlier works. Without De Quincey, Poe, and Collins there might have been no Holmes. And no genre.

Sources:

Collins, Wilkie. (1860) The Woman in White. London: Sampson Low, Son & Co.

Collins, Wilkie. (1868) The Moonstone. London: Tinsley Brothers.

De Quincey, Thomas. (1822) Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. London: Taylor and Hessey.

Emrys, A.B. (2011) Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel. Jefferson [NC]: McFarland & Company.

Kelly, Ruth. (1937) The Influence of Thomas De Quincey on Edgar Allan Poe (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California. http://digitallibrary.usc.edu/cdm/ref/collection/p15799coll20/id/385613

Doyle, Arthur Conan; Klinger, Leslie (ed). (2005-2006) The New Annotated Sherlock Holmes. New York: W.W. Norton.

Purdon, James. (December 6, 2009) “The English Opium Eater by Robert Morrison,” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2009/dec/06/opium-eater-de-quincey-morrison

Rzepka, Charles. “‘A Deafining Menace in Tempestuous Uproars’: De Quincey’s 1856 Confessions, the Indian Mutiny, and the Response of Collins and Dickens,” in Morrison, Robert (ed); Roberts, Daniel Sanjiv (ed). (2008) Thomas De Quincey: New Theoretical and Critical Directions. New York: Routledge.

Share this: