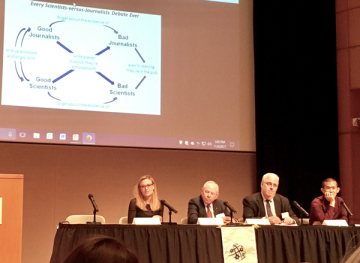

Tali Sharot, Alan Leshner, Joseph Fins, and Ed Yong

Gone are the days when science communication mainly consisted of publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Instead, there’s a “hunger” among scientists, and particularly young scientists, to communicate their work to public, said Alan Leshner, CEO emeritus of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and a member of the Dana Alliance for Brain Initiatives (DABI).

But just because the enthusiasm is there doesn’t mean that communicating science to a lay audience is an easy feat for scientists. “It’s not an innate skill, it’s an acquired skill,” Leshner said during a panel discussion at the International Neuroethics Society annual meeting yesterday in Washington, DC.

Leshner moderated the panel, “Neuroscience, Communications, and Public Engagement,” in which two scientists and one science writer discussed scientist responsibility when communicating their expertise to the public, and how best to relay that information.

It goes without saying that scientists need to practice explaining their work to a lay audience to do it effectively. It’s something we focus on with frequency at the Dana Foundation, as seen in a recent book review of Alan Alda’s book, If I Understood You, Would I Have this Look on My Face?, and our own book, You’ve Got Some Explaining to Do (available as a free download in English and Spanish). But since this was a panel at a neuroethics meeting, individual presentations focused on areas of ethical concern, such as bias and transparency.

Kicking off the talks was DABI member Joseph Fins of Weill Cornell Medical College and Yale Law School, who explored psychiatrists’ obligation to public engagement when the issue in question takes place in the political arena. Citing the American Psychological Association’s Goldwater Rule, which prohibits psychiatrists from commenting on the mental state of people they have not personally evaluated, he questioned if it’s ever proper for doctors to publicly weigh in on the mental state of political figures in the interest of public health and the common good.

His belief is yes, but with limitations and self-awareness. He thinks doctors have an educative responsibility, versus a diagnostic one, to the public in such matters. Doctors cannot be motivated by partisanship, though, he said: A scientist can’t simply disagree with a politician’s ideology and want to sway public opinion in his or her preferred direction.

Given the current political climate, the debate on this matter has been heated and widely covered by the media (Fins cited a recent Village Voice article, “Before the “Goldwater Rule”: Profiling Hitler in 1943,” as one example). When we seek information on an issue or an argument, how much does our own bias color our interpretation of what we read or hear?

Panelist Tali Sharot of University College London studies bias and is well aware of its power of persuasion. In her work, she found that people like to hear what they want to hear: They tend to trust sources that agree with their opinions and also information that they view as “good news.” It is because of these ingrained biases that Fox News tends to draw conservative viewers and MSNBC liberal ones, for example, or that we want to believe articles that say red wine is good for our health, she said.

In the context of science communication, scientists need to be aware of these biases when they present their findings, said Sharot. To use a common communications phrase—know your audience. But there is also an ethical responsibility not to use this knowledge to manipulate public reaction to their work, she said.

People trust scientists, and they must act in ways that honor and preserve this trust. The media can help, holding researchers accountable for their words and their work. The third and final panelist, Ed Yong, a science writer for The Atlantic, views himself as a watchdog, in addition to translator and storyteller.

There’s a tendency to present science as a series of facts and results, but, in fact, science is a process and gradual reduction in uncertainty, he said. Reproducing results in psychology studies, disagreements within the science community, and scientific biases based on subjects used, are all topics he’s written about, for example.

Though science coverage is often positive, it isn’t always. It’s not his responsibility to get people excited about science or to publicize a scientist’s work, Yong said. His loyalty is to his readers, and his job is to present the science in an open and transparent manner that invites skepticism and discussion.

In his closing remarks, Yong offered up four tips for good science communication:

–Ann Whitman

Share this: