This time I do a digression from my usual themes to talk about Chinese Science Fiction. But you will see that is not a great deviation: some of the topics are familiar; as William Gibson famously said: The future is already here — it’s just not very evenly distributed.

I have always been a science fiction fan and I noticed in the last years that the genre is booming in China (maybe as a way to more freely talk about current affairs disguising them about speculative fiction?)

Here are three books that I enjoyed lately. The links are to the authors or publishers pages, not any book retail page.

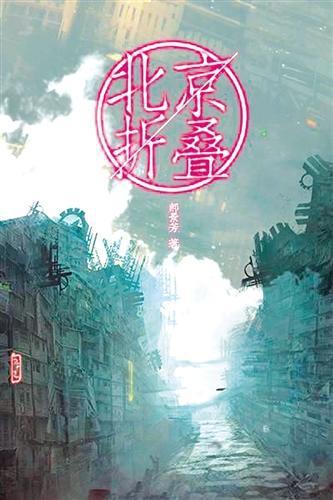

Folding Beijing by Hao Jinfang Hao Jingfang – source: The Beijinger

Hao Jingfang – source: The Beijinger

Hao Jingfang (1984) has herself an interesting background: an undergraduate degree from Tsinghua University’s Department of Physics and a PhD from Tsinghua in Economics and Management.

Both topics are present in her novella “Folding Beijing”, a multiple awards winner.

An English version has been originally published by the magazine Uncanny but is also included – together with several of her stories – in the anthology of contemporary Chinese SF Invisible Planets, edited and translated by the great Ken Liu.

A German translation is also available from Elsinor from July 2017.

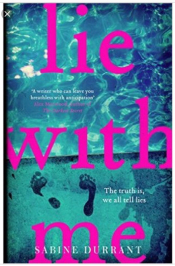

Folding Beijing original cover

Folding Beijing original cover

The context: in a not too far future, China’s capital Beijing – overloaded by millions of inhabitants – undergoes a big engineering project that split the megacity into three parts: First Space, Second Space and Third Space.

They are alternating on the surface at different times (but they’re not equal).

When one part is enjoying the sun’s light the other two are folded underground and their inhabitants forced to sleep.

Of course, the three parts are totally different: while the First Space has large green areas and modern buildings for the top 1%, the Third Space seems coming from an even more dystopian version of Blade Runner.

The story itself is short and simple. This idea, the atmosphere, the economics behind is the most striking part of the book and the city design combining old and new will remain long in your mind.

The Three Body Problem by Liu CixinThis is my favourite book among the three.

A classic hard science-fiction novel but with several new ideas and fresh blood.

I later discovered that was one of the books strongly suggested by the Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti and Barack Obama:

The scope of it was immense. So that was fun to read, partly because my day-to-day problems with Congress seem fairly petty — not something to worry about.

— Barack Obama

It was first published in China in 2006 as a magazine series and later as a book in 2008. Now even a movie has been produced: the first big-budget SF film in China (already filmed, now in post-production but not yet scheduled for release). When I read it I immediately thought that it was perfect for a movie, though it will not be easy to re-create some of the fantastic worlds described.

It was first published in China in 2006 as a magazine series and later as a book in 2008. Now even a movie has been produced: the first big-budget SF film in China (already filmed, now in post-production but not yet scheduled for release). When I read it I immediately thought that it was perfect for a movie, though it will not be easy to re-create some of the fantastic worlds described.

The Three-Body Problem was the first full-length Chinese SF work to be translated into English, in 2013. Now a German version also exist, and I am sure many will follow.

Without spoiling the story, it starts when nano-materials expert Wang Miao receives a mysterious countdown to stop his research project and he is made aware by a special joint team between Police and an international Military force that scientists all around the world face a similar threat and are committing suicide in large number.

The authorities believe this to be part of a global large-scale plot with unclear goals.

Actress Jingchu Zhang (Ye Wenjie) in the upcoming movie (2017)

Actress Jingchu Zhang (Ye Wenjie) in the upcoming movie (2017)

This is somehow linked to a VR video-game called the 3-body problem that asks players to find a solution to a planet orbiting around a system of three suns (a famous historical physics problem) and to the astrophysics alumna Ye Wenjie, who got exiled to the countryside during the Chinese Cultural Revolution, specifically at a recessive military base involved in a top-secret experiment, in the late 60s.

The historical links are quite interesting:

It was a sensitive topic and therefore we were worried about related contents causing trouble. However, the book has been out for 10 years now, and we have never had any censure from the authorities

— the author said in a recent interview.

Liu himself was a child during these trouble times for intellectuals. He wanted to be a science-fiction writer but instead of studying literature, he got a job as a power-plant engineer in Yangquan. This was entirely strategic: the stability of his career meant he could write, he said:

For about 30 years, I stayed in the same department and worked the same job, which was rare among people of my age. I chose this path because it allowed me to work on my fiction,” he says. “In my youth, when I tried to plan for the future, I had wished to be an engineer so I could get work with technology while writing sci-fi after hours. I figured that if I got lucky, I could then turn into a full-time writer. Now looking back, my life path has matched my design almost precisely. I believe not a lot of people have this kind of privilege.

Cixin Liu clearly loves golden-age SF authors like Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke (well, me too; this is probably why the novel resonated so good with me).

Nevertheless, The Three-Body Problem turns a drained concept into something absolutely mind-unfolding.

After having laid down the stages (the military base during the Cultural Revolution and its project, the video-game and its community of players, the present time and the plot) the story starts to take speed and turns into a gripping science-fiction epic (two sequel books came also out but you can read this book as a perfectly stand-alone self-concluding one).

The Lifecycle of Software Objects by Ted ChiangTed Chiang is actually a US writer; both his parents are emigrants from China but he was born in New York as Chiang Feng-nan.

He has achieved some recent fame when his novella “Story of your life” has been adapted in the movie Arrival in 2016.

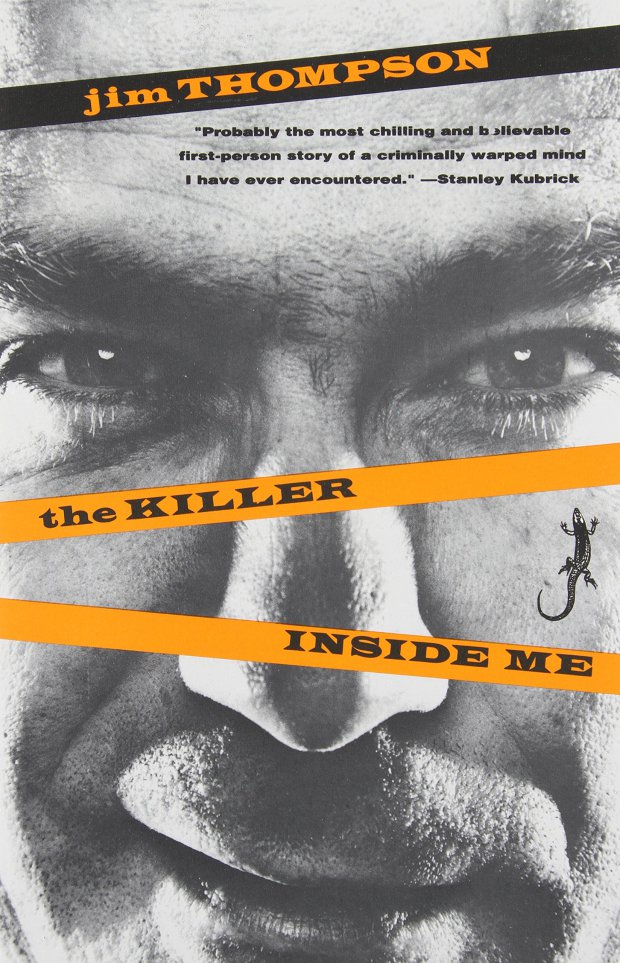

Subterranean Press hardcover

Subterranean Press hardcover

“The Lifecycle of Software Objects“ (2010) follows Ana Alvareda – a previously animal trainer turned software tester due to narrowing job market – who is hired by a startup to train “digients” (short for “digital entities”), artificial intelligences that have been created within a digital world (similar to Second Life).

Originally the digients have been given anthropomorphic animal avatars to make them seem cuter and hopefully more marketable and are essentially just baby digital pets.

Ava’s task is to help them develop personalities and wills of their own over time, until they have enough traits to be interesting for the customers.

The story spans over a twenty-year period with small snapshots when we see the development of the digients (as well as those of competing companies); we watch them grow up and learn new skills and gain an understanding of their world; ultimately, Ava faces the crisis when the proprietary virtual platform of the startup is shutting down. What will happen to the digients when their universe will cease to exist? What can Ava do?

Ted Chiang – source: Wikimedia

Ted Chiang – source: Wikimedia

Chiang’s novella is particularly appealing for anybody interested in artificial intelligence. It is helping that Chiang himself is graduated in Computer Science: the digients and their evolution – they keep getting smarter and more fascinating – feels totally believable. As well as the normal cycle of technological innovation and business development: the original platform becomes obsolete, new technologies and new companies come, other companies go under, hype turns to bust. Anybody who has worked in the software industry will recognise this world.

And after reading this book, it makes you really wonder about these promises for A.I. surpassing human knowledge and solving all humanity problems. The book theory is that A.I. would be difficult and maybe impossible to tailor to our specific needs. The best A.I. might not have any commercial application whatsoever and the smartest A.I. might be frozen by so much obsessive-compulsive disorder that they wouldn’t listen to anybody. Or you might create the perfect smart personal assistant but then after the training process it will only be loyal to one specific person regardless of your attempts to transfer its loyalty to other people so you can sell instances of it.

We’ve been accustomed to thinking about A.I. as something that will spontaneously generate out of game-playing or increasingly complex problem-solving algorithms, but Chiang makes a pretty compelling case that A.I. will instead come out of interactions with humans who teach computers how to think and communicate in a way that is meaningful to us.

Advertisements Share this:- More