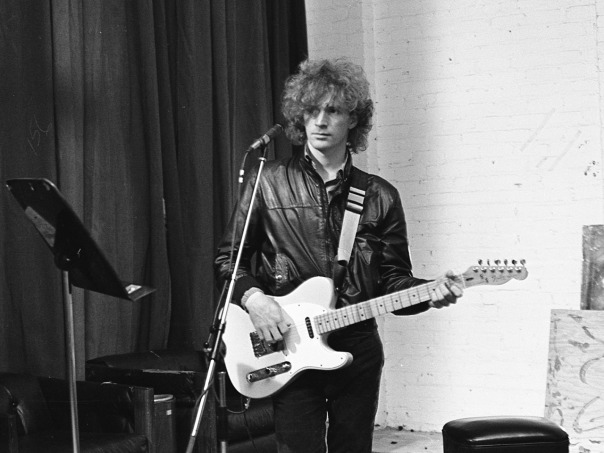

Scott Miller recording Two Steps from the Middle Ages, 1988. Photo by Robert Toren.

Scott Miller recording Two Steps from the Middle Ages, 1988. Photo by Robert Toren.

On the Loud-Fans listserv in the 1990s, it was common to refer to Scott Miller as “Our Scott.” This usage was mainly to clear up any confusion with another Scott Miller, whose alt-country band called the V-Roys were popular at the same that Our Scott Miller’s band, the Loud Family, was active. The name Loud Family could cause confusion, too, because it was borrowed from the subject of a somewhat infamous reality TV show from the 1970s called An American Family. Our Scott Miller was multiply obscured, sometimes by his own choices. Even the praise he got from America’s foremost rock critic, Robert Christgau, in 1990, called him “a prototypical eighties artist: serious, playful, skillful, obscure, secondhand … rendering the ostensibly public essentially private.” (Another critic called his music “obscurantist pop.”)

That same year, Our Scott joked that “Erica’s Word,” the catchy 1986 single by his previous band, Game Theory, had only managed to earn them “national obscurity, as opposed to regional obscurity.” And he never relinquished the notion. On a Loud Family album released in 2000, pointedly named Attractive Nuisance, Miller sang of his own “willful obscurity” (summoning the rock-critical cliché “unjustly obscure”) and then quit making records. Thirteen years later he killed himself. He had just turned fifty-three.

Over the last couple of years, the revival label Omnivore Recordings has been re-releasing Game Theory’s entire catalog, all of it out of print since shortly after the band broke up at the end of the 1980s. Two months ago, Omnivore delivered the final Game Theory album, 2 Steps from the Middle Ages (1988), bringing the project to completion. That was followed, earlier this month, by another nominal Game Theory release: Supercalifragile, a crowdfunded album of songs derived from recorded fragments, notes, and ideas Our Scott was kicking around (including that title) just before he died, intending to make what would have been the first new Game Theory album in a quarter century. He had gone so far as to contact members of his old band. The project was revived by his widow, who enlisted pop maestro Ken Stringfellow to oversee a posthumous LP, something more than a tribute but less than a true Game Theory album, a sort of speculative assembly of a ghost’s ephemera, and with an initially ghostly presence, too: Supercalifragile has not yet been publicly released, only privately distributed to fundraising campaign backers. (The rough mix of one of its songs is on YouTube.) A few of the dozen or so musicians who helped write and played on the album are famous enough to draw limited outside attention to it, but mostly as a curio. With the Omnivore series complete, future opportunities to write about Our Scott will be few. Following the life, the afterlife, too, is coming to an end.

For me, 2 Steps from the Middle Ages will always be a beginning. Although it was the final Game Theory studio album, it was the first one I encountered, and I probably know it better than I know any of Our Scott’s other recordings. I still think it might be his best, which may simply owe to our tendency to prefer the first music we hear of an artist, because we revisit the freshness of our discovery with every listen—we stir up the excitement of falling in love. In any case 2 Steps is almost certainly the most accessible introduction to Our Scott’s music. I bought it new on vinyl in 1988, just after it was released. I had never heard of Game Theory and knew nothing about the band or the album except that it had a sticker on it that proclaimed, “West Meets Easter”: a wordplaying reference to Game Theory’s Bay Area base and the album’s production by Mitch Easter (which was the fourth straight Game Theory album Easter produced), who was the most important force in North Carolina pop and rock music at the time. He had a recording studio in Winston-Salem, where he’d put himself on the map by coproducing R.E.M.’s first two records in the early 1980s (he went on to produce albums for many bands), but I was a fan of Easter’s own group, Let’s Active, before I embraced R.E.M.’s “music for mushheads,” as Robert Christgau correctly called it (while also correctly praising it). I liked Easter’s big guitar hooks and riffs, derived from Led Zeppelin, married to his nasally mischievous voice–echoing Robert Plant’s overlooked but integral elfin side–and delivered by an impish fellow who’d have fit right into Mod-era London; and I was especially intrigued by his deployment of lyrics as textural and tonal elements. Rather than make explicable sense, the words formed suggestions of feeling, or perhaps they were the feeling. It was always only a matter of time before R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe revealed, on Lifes Rich Pageant, that his romantically garbled mumbling was really a prelude to clarity. But Easter never capitulated. Christgau complained: “If only Mitch Easter had something to say.” Our Scott, a lover of James Joyce and T.S. Eliot, was better disposed to try to understand Easter, from whom “I learned … almost everything I know about record production.” Scott identified in Easter’s songs “what I’d call prophetic weight. His recurring theme was people—in love relationships especially—wandering into a world of undreamt-of emotional turmoil, and how that alone makes the human horizon look dark.”

In 2007 Easter released a song, “Ton of Bricks,” that opened with the line, “The weight of saying something,” and decided: “Weight must be the message.” He was finally announcing what Our Scott had descried three decades earlier. But Scott’s description of Easter’s lyrics also perfectly and perhaps better applies to his own; he may have learned not only about record production from Easter but about songwriting as well. His recurring theme was people—in love relationships especially—wandering into a world of undreamt-of emotional turmoil, and how that alone makes the human horizon look dark.

Perhaps in 1988, when 2 Steps from the Middle Ages came out, the darkness was farthest away. Our Scott had made an ambitious artistic statement the previous year with Lolita Nation, a prodigious, extravagantly inventive double album built around a dozen or so discrete pop songs interlarded (and sometimes corrupted) with mad-scientist sound potions and other experiments with their lids left off: assemblages of musique concrète, melodic and lyrical bric-a-brac, unrelated riffs jammed together to make side-filling instrumentals, and so forth. For all its literary and mathematical intelligence, its sheer workaholic accomplishment, and its concept-album aura of the magnum opus, there’s something a little jejune about Lolita Nation; in retrospect, it might better have been either stranger or less strange than it is. 2 Steps from the Middle Ages, on the other hand, is a work of steadier maturity and creative assurance. The album’s first song approaches on the fade-in runway of a drum pounding out 4/4 quarter notes, lifts swiftly up off the ground, and immediately takes the proper altitude for its survey. It’s first lines are: “Flying in/Over Asia, low”–a foreign world regarded from an aerial view, yet near enough to the ground to discern the details of the landscape below. The rest of the LP maintains that slight elevation at jet speed, in midair but not high-flown, and making frequent returns to street level. But even those touchdowns maintain frictionless velocity and detachment. “In a DeLorean” is the name of one song. The narrator of another declares, “I’ll walk around the city snapping pictures uninvolved.” Game Theory’s idiosyncratic sound–“foamy,” Mitch Easter called it–is clarified, not obscured, by subtly polished studio engineering, and Our Scott’s busy, serpentine melodic and lyrical routes often lead to rich payoffs that seem in retrospect to have been waiting there all along. He was a master of creating extremely difficult routines and then sticking the landings.

The straightforward quality of 2 Steps as compared to Lolita Nation was imposed by Game Theory’s record label (who dispatched a pair of extra engineers to the studio), which of course had commercial priorities; but there were surely internal, organic reasons for the new direction, too. After constant personnel changes in Game Theory’s early days, a stable lineup had formed by the late eighties; perhaps this new cohesion, as both professional and musical family, inspired Our Scott to make a more traditional rock-group album. And maybe he was just happier. He was twenty-eight, the greatest age anyone ever turns. His band had not achieved mainstream popularity, but they were not unpopular either. Fans bought Game Theory’s records and came to their high-energy shows. The group had good press and a good indie record label. Our Scott’s beautiful girlfriend Donnette Thayer joined Game Theory around 1987 and contributed not only her voice and musicianship but also a dose of Hollywood glamor and heat-seeking rock-and-roll instincts (among her roles was an active effort to increase Game Theory’s exposure, spearheading music video and other promotional efforts). Our Scott claimed that he had never sought stardom: “I was about seventeen when it occurred to me that I don’t want to be a commercial success story,” he said in 2011, long after he’d become a commercial failure. But he spent three decades recording and releasing his songs, assembling and reassembling a band around him, and getting up in front of crowds and playing. By all accounts he liked attention. He was a natural performer and quite happy in the spotlight. It was perhaps never brighter on him than it was in 1988.

Donnette and Scott, 1986. Photo by Robert Toren.

Donnette and Scott, 1986. Photo by Robert Toren.

2 Steps from the Middle Ages is bright music, even when it sees darkness on the human horizon–or when the darkness is right at arm’s reach. Although it is no concept album like Lolita Nation, it does follow a progression which culminates in a plaintive lament on the penultimate track, and it’s straight out of high school: “I got a feeling the votes are in and I got none/And all I want is oooooone!” Notwithstanding his lyrical complications, Our Scott had a disarmingly deft way with slang and received and conversational language (“same deal,” “Sodium Laureth Sulfate,” “must have been your little sister I saw”); and even his customarily oblique lyrics are ornamented by clarity and directness at the primary level of the phrase: he had a gift for trenchant and sharp language hooks that whole songs could be securely hung from—prophetic weights. They don’t tend to read well on the page (song lyrics seldom do), but when Our Scott sings “Let us make our mistakes young,” “She just wants it to be okay,” and especially “all the lovely eyes to see” on 2 Steps‘ elegiac coda, “Initiations Week,” the lines’ capacity to grab and keep hold of the ear can be powerful, and he must have known it: he habitually lifted lyrical fragments from his own songs and replanted them on later albums, sometimes in spiky or garish ways so as to draw extra attention to them.

The strongest attention was drawn by his physical voice, which was at once what made his music unique and what alienated so many listeners from it. He told an interviewer: “I’ve always hoped my singing would fall into that category of being technically poor but emotionally engaging for a few people.” He called his voice a “miserable whine,” cheekily coopting a cranky critic’s complaint. It was a was naturally reedy, straining and high-pitched voice, so overfull of feeling that it would often shoot up into falsetto, the rising counterforce to his prophetic weight: it was like a balloon cut loose or a kite gusted up; a rational argument suddenly hijacked by desire or desperation; a twin-prop juddering airborne over Asia, low. Although he was quite capable of singing in a lower, more controlled register, especially as he moved through his thirties and his voice continued to deepen with age, he persisted in singing “like a drugged twelve-year-old,” as he described his vocals on Lolita Nation. Our Scott’s voice carries all the undreamt-of emotional turmoil that he was otherwise at pains to conceal. It can be wildly pleading or painfully confused, orbiting in rapturous dreamspace or blown like a feather by diffidence or disbelief. It is a passionate unearthly overwhelmed voice–a supercalifragile voice.

When I spoke with Mitch Easter about Lolita Nation, we naturally fell into a discussion of Scott’s commercial failure. Mitch thought Game Theory might have done well to relocate to the east coast, where the prevailing indie sound was earthier and more organic than it was in California, especially among practitioners of the arty, twee “Paisley Underground” style that flowered on the Pacific in the 1980s. Or perhaps Scott might more simply have kept the name Game Theory after he regrouped in the early 1990s instead of rechristening his new act the Loud Family, throwing fans off his scent; but on the other hand, the Loud Family’s first album, Plants and Birds and Rocks and Things, attracted plenty of press coverage, including a spotlight from no less an authority than Rolling Stone magazine, which included the Loud Family in a 1993 “New Faces” triple-feature with Liz Phair and Radiohead. It’s quite plain, though, why those two acts hit the big time and the Loud Family did not. Obscurity was Our Scott’s great subject, and his compositional strategy, and his lot in life.

Obscurity even became an inadvertent part of his name. Another common usage on the Loud-Fans listserv was the construction “ObScott.” This was shorthand for “obligatory Scott content,” which was a way of acknowledging that he was an infrequent generator of news, especially as the 1990s wore on. Outside of his brief biannual emergences with new Loud Family albums, each followed by a brief domestic tour, he was not a public figure, holding down a day job in Silicon Valley and raising a family. Loud-Fans discussion threads naturally tended to drift away from their nominal subject. It was a courtesy to try to introduce, with the phrase “ObScott,” some pertinent content into any given posting to the listserv. Over time, “ObScott” also seemed to collect secondary meanings: Obscure Scott, Oblique Scott (he himself was fond of Brian Eno’s “Oblique Strategies”), then Obsolete Scott, and finally Obliterated Scott. So many “Obs” managed to accrue to the prefix—even, for me, the made-up language “ob” spoken to each other by a mother and her young son in Don DeLillo’s novel The Names. DeLillo’s ob is a Pig Latin-like idiolect that is—to return to Robert Christgau’s summary assessment—“serious, playful, skillful, obscure, secondhand … rendering the ostensibly public essentially private.” A posthumous biography of Our Scott, Don’t All Thank Me at Once, is ardent and thoughtful but its natural bias is decorous and protective of its subject. It was written by a longtime avowed fan, Brett Milano, and published by the Loud Family’s last record label, which had been founded by a friend of Scott’s partly in order to release his music. (To be fair, the biography came about only after a proposal for a book about Lolita Nation to Continuum’s 33 1/3 series was rejected.) Surely Supercalifragile will eventually go public, but the priority with Our Scott has nearly always been private–and “Our Scott” is itself the language of possessiveness, of course. Both Milano’s biography and Supercalifragile are welcome and honorable ways to keep his legacy alive; but despite Omnivore’s Game Theory reissues, and notwithstanding that Scott Miller will likely never be a household name (no matter how many other Scott Millers we distinguish him from), we are mostly still speaking in ob about him, unable or unwilling to loosen our collective tongue.

A credible rumor circulates about Our Scott’s method of suicide, which has never been publicly disclosed and was assertively omitted from his biography. Even his death is obscure. A little internet research reveals the rumor to be very likely true. (I’m sorry if it is not and I have offended those close to him.) It is so shocking and gruesome that it rattles the very bones and spirit to ponder it. But it deepens his music. His death is his final prophetic weight. It bears the despair that was always in his art, of course; but the weight itself is borne by the strength of Scott’s courage, discipline and conviction, his unflinching stance before the impenetrable roaring hugeness of what may be called the truth, or existence, or his own obscurity or sense of failure, or even God. When inevitably more understanding of his life and death transpires, he and his music may be released from the tethers of Our Scott and ObScott to stand in the light, for all the lovely eyes to see.

Scott’s sketch and notes for the cover of Two Steps from the Middle Ages. Photo by Robert Toren.

Advertisements

Share this:

Scott’s sketch and notes for the cover of Two Steps from the Middle Ages. Photo by Robert Toren.

Advertisements

Share this: