I am beginning the New Year rather late this year as you might have noticed. Clearly, either my body clock has taken a while to kick in or I have been in a state of denial about the existence of 2017 (note also that I am glossing over my blogging inactivity in December). However, I do intend finally to begin my blogging year and return to tackling my Landing Bookshelves Reading Challenge albeit with the usual digressions along the way. As you will know, said digressions tend to be frequent, so my TBR pile is not getting any smaller; and will in fact probably never shrink appreciably. I will just have to live with that, (it’s a hard life!).

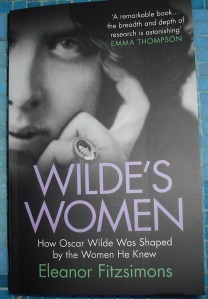

True to form, my first post of the year features a non-TBR book, Wilde’s Women by Eleanor Fitzsimons (Duckworth Overlook, 2016). The sub-title runs: How Oscar Wilde Was Shaped by the Women He Knew, and this was the part that particularly attracted my attention. Wilde is probably more widely associated in the public consciousness with the men in his life, rather than the women. The author has given both his mother and his wife their rightful due in this book. Eleanor Fitzsimons’ exploration of the female angle in Wilde’s life interested me because I have previously read Joan Schenkar’s fascinating biography about his niece Dorothy ‘Dolly’ Wilde (the daughter of Oscar’s older brother Willie and his second wife Sophia Lily Lees). As it turned out, Oscar’s enduring charisma and reputation cast a long shadow over Dolly’s frequently unhappy life. She bore a striking physical resemblance to her famous uncle and consequently spent her life trading upon it. As Eleanor Fitzsimons points out, this tendency caused awkwardness in her relationship with Oscar Wilde’s son, Vyvyan Holland when they finally became acquainted in adulthood. She was said by her mother to have inherited ‘a fair share of the family brains’ but Dolly was perhaps damaged by the weight of expectations put upon her so young.

Of course, properly speaking Dolly Wilde cannot be counted as one of Wilde’s Women (as defined by the terms of the sub-title) since she was born while he was imprisoned and she never actually met him and so represents a rather sad epilogue to the Wilde story. If however we do include Dolly Wilde in an account of the women of Oscar Wilde’s family, then it becomes apparent that his life and work was bookended by two striking and fascinating women. At Oscar’s genesis, we find his mother Jane Elgee Wilde (known by her pen name Speranza) and towards the end of his life, the birth of Dolly, bearing the Wilde mythology onwards. On the face of it, it appears that Speranza provided the seeds of the literary and artistic talent, which blossomed into Oscar and yet which failed to bear fruit in Dolly Wilde. No story is ever that simple however, but such a literary legacy would have been difficult to follow for any descendent. I wonder how Oscar’s sons coped with the pressure of his literary legacy, to say nothing of the effects of losing his presence in their lives after the trial.

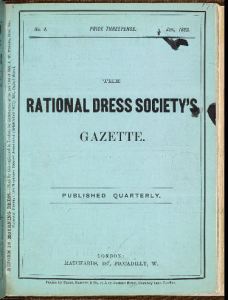

The section of the book that intrigued me the most was the chapter discussing Wilde’s stint as editor of a women’s magazine, an episode that was completely new to me. In April 1887, Oscar Wilde was invited by the publishers of The Lady’s World to revitalise and generally to add celebrity lustre to the struggling magazine. This was an illustrated monthly magazine, on sale for a shilling, which was struggling in a busy market. For instance, The Ladies’ Companion was another illustrated magazine aimed at a similar audience at the same price. Wilde was interested in editing and writing for the magazine but he insisted on a name change, more in keeping with his progressive ideas, hence The Woman’s World. Wilde suggested that the latter was much more suitable for a magazine that wished to be, ‘the organ of women of intellect, culture, and position’. He wanted to create a magazine that talked about what women thought and felt and not merely, about what they wore. I was amused to note that fashion was pushed to the back of the magazine in this brave new venture. Some previously included sections vanished altogether under Wilde’s editorship, such as ‘Fashionable Marriages’ and ‘Pastimes for Ladies’. However, I cannot help feeling a vague curiosity about the nature of those suitably ladylike activities!

The section of the book that intrigued me the most was the chapter discussing Wilde’s stint as editor of a women’s magazine, an episode that was completely new to me. In April 1887, Oscar Wilde was invited by the publishers of The Lady’s World to revitalise and generally to add celebrity lustre to the struggling magazine. This was an illustrated monthly magazine, on sale for a shilling, which was struggling in a busy market. For instance, The Ladies’ Companion was another illustrated magazine aimed at a similar audience at the same price. Wilde was interested in editing and writing for the magazine but he insisted on a name change, more in keeping with his progressive ideas, hence The Woman’s World. Wilde suggested that the latter was much more suitable for a magazine that wished to be, ‘the organ of women of intellect, culture, and position’. He wanted to create a magazine that talked about what women thought and felt and not merely, about what they wore. I was amused to note that fashion was pushed to the back of the magazine in this brave new venture. Some previously included sections vanished altogether under Wilde’s editorship, such as ‘Fashionable Marriages’ and ‘Pastimes for Ladies’. However, I cannot help feeling a vague curiosity about the nature of those suitably ladylike activities!

From The Ladies’ Companion.

As Eleanor Fitzsimons makes clear, many intellectual and professional women liked and respected Oscar Wilde and were very happy to contribute articles to his re-vamped journal on various important subjects. One topic covered by The Woman’s World was women’s dress and its suitability, practicality and healthiness. Wilde, as well as his wife Constance Lloyd was an active supporter of the Rational Dress Society. In an article for The Woman’s World he wrote,

From the Sixteenth Century to our own day, there is hardly any form of torture that has not been inflicted on girls and endured by women, in obedience to the dictates of an unreasonable and monstrous Fashion.

As I am writing this, I wonder what Wilde would have thought of the current UK parliamentary enquiry into the issue of women forced by employers to wear high heels at work. I am sure he could have come up with a riveting deposition to the enquiry on the subject. His idea was that in time, ‘the dress of the two sexes will be assimilated, as similarity of costume always follows similarity of pursuits’. Sadly, it seems this has not yet happened; apparently, women still need to wear heels to do exactly the same job that a man does in flats. We certainly need a witty Wildean epigram for the shoe question.

As I said above, Wilde attracted many talented female contributors to The Woman’s World including trade unionist Clementina Black, feminist writer Julia Wedgewood, suffragist Millicent Garrett Fawcett and journalist Charlotte O’Connor Eccles. Therefore, not only was women’s dress debated within the pages of the magazine but also the extension of the suffrage to women and women’s right to be educated and to live useful and worthwhile lives. This range of content is what surprised me the most and Fitzsimons has added a great deal to my impressions of Oscar Wilde, with his support for so many radical women writers and activists. It is easy to think of Wilde in terms of witty epigrams and sparkling conversation, without stopping to think about what lay beneath the polished surface.

Sadly, Wilde’s stint as an editor did not last very long; the last edition bearing his name came out before the end of 1889, so he clocked up a mere two years. Fitzsimons makes clear that Wilde did much that was worthwhile in his role, but admits that,’ While his sincerity and sympathy were never in doubt, his suitability to deal with the day-today challenges of bringing out a magazine on someone else’s behalf was’. Turning up regularly to the office and dealing with the minutiae of getting a magazine to press proved to be beyond his capabilities. Tellingly, The Woman’s World did not long survive Wilde’s departure, having reverted to its original style of content without his dynamic input.

Because of reading Wilde’s Women, I am in danger of encountering many literary digressions; I plan to follow up ideas that I have gleaned from the wonderful range of sources used by Eleanor Fitzsimons. My hopes of acquiring a copy of one of the volumes of The Woman’s World was somewhat dashed however when I saw how much a dealer on ABE Books was charging. Perhaps I was naive in thinking that I might be able to buy one for only a few euros…

Credits: Many thanks to Eleanor and the publishers for The Landing’s copy of this book. If you wish to discover more about her work, here is a link to Eleanor’s blog: https://eafitzsimons.wordpress.com/about/

Additional pictures: As ever, thanks to Wikipedia and also to the website of the British Library.

Advertisements Please share