An interesting coincidence: after an intense conversation about the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, my department commissioned a group of volunteers to draft a public statement. I was among the group of, at various times, six to eight people crafting the text collaboratively over Labor Day weekend. The brief we received from other professors who attended the English Department retreat was not just to decry neo-Nazi terrorism, but to point how Robert E. Lee, one of our college’s namesakes, is a hero to white supremacists. If the institution we gladly teach at doesn’t address this–if we don’t address it in our classrooms and office hours–we’re giving cover to the haters.

At the same time, I was preparing to lead a discussion section of our first-year reading, Our Declaration by Danielle Allen. One of Allen’s main arguments concerns the collaborative composition of the Declaration of Independence. She traces the negotiations that, over months, shaped that document, and holds it up as a model for how a group of citizens can reason their way towards a political judgment.

I wasn’t always persuaded by Allen’s book, but I was often moved by it–not just by her personal stories, but by her evangelical passion for “slow reading,” democracy, and equality. I enjoyed discussing it with our very smart students, who walked away still in debate, and then hearing Allen’s speech at Convocation. I sat up high in the auditorium and watched shock ripple through the audience when she suggested renaming the institution “Chavis, Washington & Lee” (in 1795, John Chavis was the first African American to graduate from a college or university in the US, and that was from an earlier version of W&L, Liberty Hall Academy). One of my first thoughts is what a former student said later: “Sounds like a law firm.” Reasonable people can differ on whether our institution, which has already had a few different monikers, should be renamed. But it is time to talk about it, so I appreciated Allen’s provocation.

Likewise, I found the process of composing our English Department declaration inspiring. I know our document is trivial. But although the co-composers had various backgrounds and temperaments, urgency united us, as well as what I think of as the core values of my profession: openness to respectful debate; honesty; precision; and a belief that words matter. Across differences in rank, too, the writing process was democratic. I’m sure I’m being sentimental, but our wrangling over words felt like one of those rare moments a university lived up to its own idealistic rhetoric. I remain happy to have been a part of it.

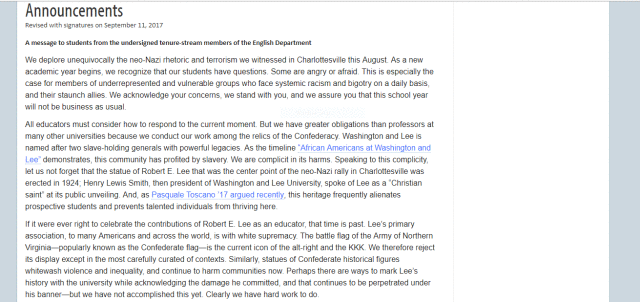

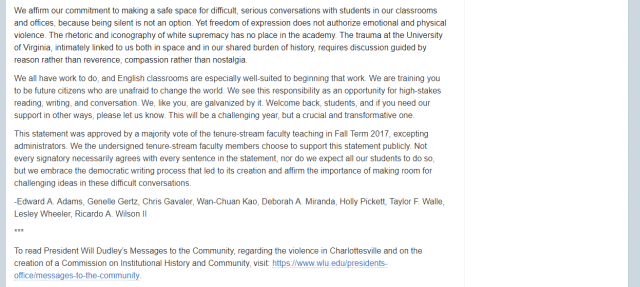

In the department’s passion to make a joint statement, however, we didn’t agree on a process or timeline, and we all came out of the retreat with different expectations as to what would happen next. Things got messy. We voted to put it on Facebook, where it generated an extraordinary range of responses (although angry voices quieted somewhat after one right-winger identified himself as a Thor-worshiper), and also on the department web page. A senior member of the administration asked us to take it off the latter and we did so (screen shots below).

Ever since, people have been asking me some version of the question, “so why is this controversial?” Sometimes it seems impossible to to describe to those outside the W&L bubble what the view looks like from here, and vice versa. And I can’t speak for the whole department–these answers are my own.

Ever since, people have been asking me some version of the question, “so why is this controversial?” Sometimes it seems impossible to to describe to those outside the W&L bubble what the view looks like from here, and vice versa. And I can’t speak for the whole department–these answers are my own.

But what seems plain and honest to me personally is that W&L has a history of celebrating Robert E. Lee without acknowledging the context or consequences of that legacy. In the mid-nineties, I attended a baccalaureate ceremony in which the speaker, a minister, commended Lee to us as a proto-Civil Rights leader, because he’d taught his slaves to read. My Yankee jaw dropped right to the well-groomed lawn, but eventually I picked it up and got back to work. I had apparently time-traveled back to the Confederacy, but I just did my best to ignore the crazy rhetoric and teach my heart out. After all, I’m helping to provide a top-notch education to deserving students, and that’s work I believe in.

Yet how is it honorable to commend the good without acknowledging the harm? W&L is academically stellar, but it’s also the least racially diverse top liberal arts college in the country. Lee made laudable contributions to our school, but he also dedicated his military genius to defending the dehumanizing violence of slavery. To praise him without, in the same paragraph or page or oration, admitting the damage he helped cause–it’s ethically indefensible. See W&L’s “Our Namesakes” page for one of many public failures to get the balance right. Or look at our art and architecture. To hold school events in Lee Chapel, as if it’s normal to celebrate academic achievement with a portrait of the general in Confederate gray in the background–that damages the spirit of inclusiveness many of us work daily to foster.

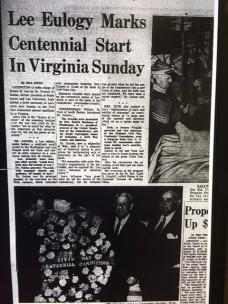

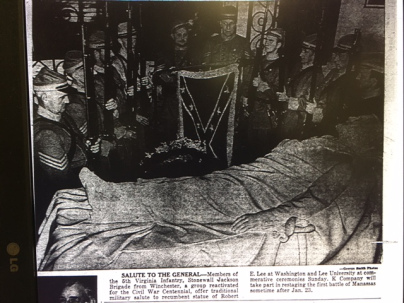

Many community members have grown up with or just become used to this soft-focus hero worship of Lee, while also considering themselves anti-racist. Those positions are inconsistent in a way that becomes more obvious daily. I do hope for better, but we’ll see. Change comes slowly. In the meantime, here’s an article from The Lynchburg News I found during unrelated research yesterday. It turns out that the centennial of the Civil War was much celebrated in these parts, starting in 1960 and 1961. While the Civil Rights movement was in full swing, The Lynchburg News ran an intermittent “Confederacy Column” so that no one would forget to honor those southern soldiers.

It’s the partial forgetting I worry about.

Share this:

Share this:- More