I love zombie movies, but even I have to admit that the genre hit its saturation point a few years ago, and we’re due for a long stretch without them. But in the waning days of any genre’s over-development, there are always bound to be a few gems that take overly familiar concepts and do something unique, clever and stirring with them. Pontypool is one of them. Released in 2008, this Canadian indie standout has the courage to go for atmosphere rather than viscera, and turns a tired concept into a subtle form of dread. In a genre that virtually demands you go over the top, Pontypool plays it cool and provides the kind of horror experience you’re not likely to come across very often, powered by a solid proof of concept, enjoyable acting and deft execution.

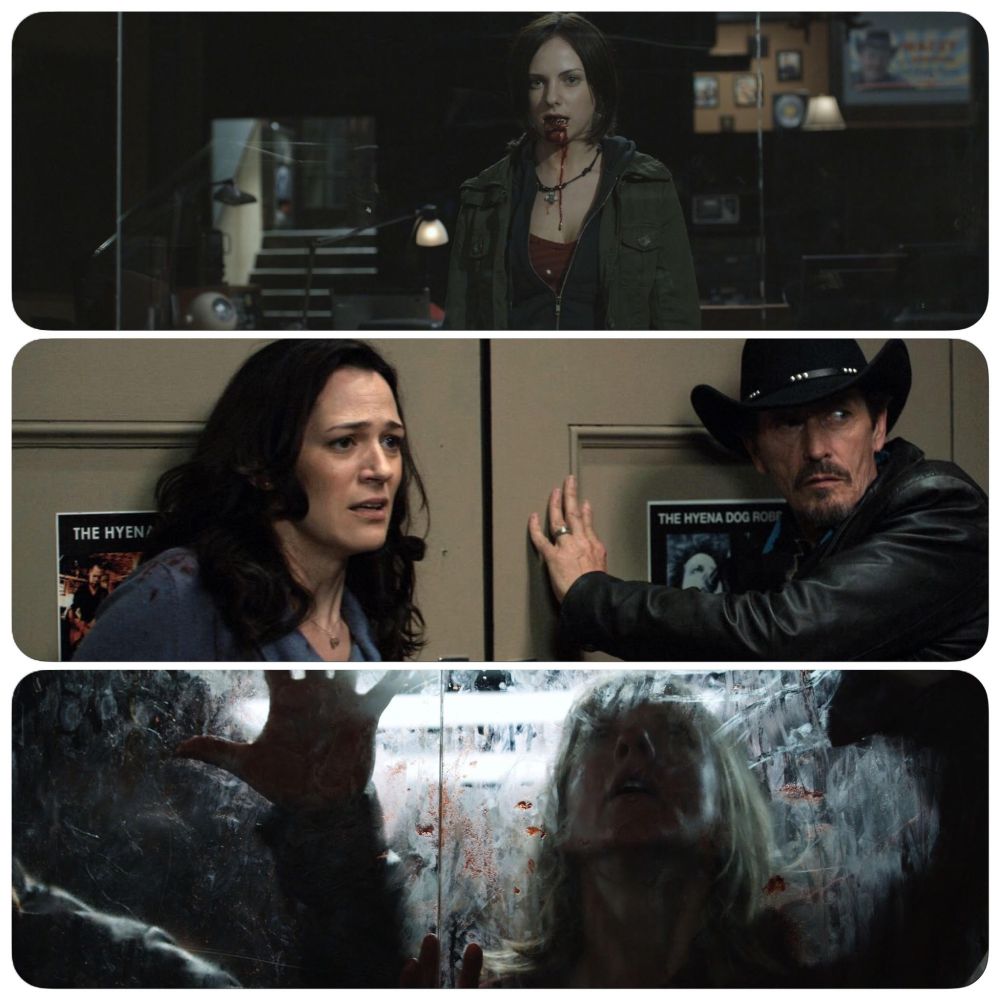

Grant Mazzy, an arrogant shock-jock exiled from his old gig in the big city, is doing his career penance by hosting the morning show at a local radio station in the small town of Pontypool, Ontario. Housed in the basement of a church, Mazzy in the Morning is run by sound engineer Laurel-Ann Drummond, a spunky hometown girl recently returned from a stint in Afghanistan and produced by Sydney Briar, a weary divorcee who is having second thoughts about her decision to hire Mazzy. As the story begins, it’s just another morning at work, with Mazzy being the kind of dickhead that got him huge ratings until it got him fired, and with Laurel-Ann and Sydney trying to keep Mazzy from alienating their entire audience. Then they get a strange phone call that there’s a mob trying to storm a doctor’s office downtown. The people are all repeating gibberish as if they’re speaking in tongues, and it reminds Mazzy of a disturbing encounter he had earlier that morning, while on his way to work, with a townsperson doing the exact same thing. Very quickly, the three realize that there is something really horrible going on in the Canadian boondocks, and they’re the only folks able to tell the world about it.

As Pontypool descends into monstrous chaos, the only action we see is from within the broadcasting booth, where Grant, Laurel-Ann and Sydney have safely barricaded themselves while details come to them in the form of frantic phone calls from traffic reporters and dying listeners. We don’t see a single gunshot get fired throughout the entire movie. (Remember, this is Canada we’re talking about here.) The vector of infection comes from a most unexpected source, putting every character at the kind of risk that really lets you know that nobody in this thing is safe. The few characters we do see act with uncommon intelligence for a horror movie, which deprives us of a lot of predictable and unentertaining carnage. And there is a conspicuous absence of the old “the only thing worse than the zombies are the other survivors’ motif.

In this story, the situation devolves too quickly for people to turn on each other; they are all too preoccupied with staying alive. But most importantly, the film fixes the location in a very tight spot, forcing the characters to listen to the end of the world more than take part in it, and it is this where Pontypool gets its best material. It’s all a bit like if Orson Welles decided to do Night of the Living Dead, and I mean that as a compliment.

As Grant, Laurel-Ann And Sydney listen to the world outside of their pitiful little radio station fall apart, their story made me think about the power of communication to bring people together, whether they are on different continents or they are in two entirely different states of mind. The town of Pontypool itself is in the middle of nowhere. The radio station is itself all by itself in a forgotten corner of a forgotten burg. And in their own way, the heroes are all isolated from each other and the people in their lives. They make their living talking to people, but at a time when their talents are needed the most, they find that perhaps staying on the air might be the worst possible thing they can do, for reasons best left discovered by the viewer. What I will say is that the movie’s moment of truth is when Grant and Sydney realize how people are being infected, realize that they are infected themselves, and contrive a way to keep themselves from transforming into something inhuman.

They say that really good zombie movies aren’t about zombies at all. The zombie thing is just a stand-in for a bigger issue. And here, it’s all about why and how we talk to each other in an age of sound bites, half-truth and doublespeak. We are under a daily assault by politicians, pundits, marketers and journalists who all wield our language like a madman’s straight razor. And at the end of it all, Pontypool is about how language can confuse us so badly that we begin to doubt not just the words we use to communicate with each other, but who we’re trying to communicate with in the first place.

If you don’t believe me, just say the first word that comes to mind, and then repeat it over and over and over again until you get to the point where the word doesn’t even sound like the word anymore. Now imagine yourself locked in an endless argument with somebody who simply will not see your point, but you’re yelling back and forth in that nonsensical English where words have ceased to have any meaning. Now imagine everybody yin the world screaming back and forth like that and see if you don’t feel the hairs on the back of your neck rise. That is the future of Pontypool. And it’s probably a whole lot possible than any other vision of zombie Armageddon. In Pontypool’s terms, we’re all halfway to becoming zombies already.

Like this:Like Loading... Related