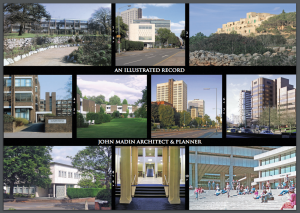

Having established my theoretical approach, for example, via the work and writings around Stefano Canto, I have been focusing on the architecture of the twentieth century created by John Madin (1924-2012).

Madin owned the third largest architectural practice in the UK for a period and his output dominated the city of Birmingham. He has suffered the ignominy of most of his major works being demolished in the last 15 years. As I write the Birmingham City University Conservatoire, 1964-73, is undergoing demolition. I captured this building as part of the Pause Project in the Spring 2017, figure 1, along with the Clarendon Suite, 1972 (Hagley Road) and his own studio/offices, 1967 (123 Hagley Road); both are pencilled in for demolition, due to redevelopment plans. The latter (123 Hagley Road) I plan to return to in the next few months to gather more images.

Clawley, 2011, describes Madin’s work “closely reflects the evolution of the modern movement between 1950 and 1975. Moreover, his major buildings are concentrated in a compact area of Birmingham weather changing styles can be studied relatively easily from the delicate early curtain walling with contrasting bands and materials to the later, strong remodelled concrete panels With their windows inside, and service towns of dark engineering brick” pp1.

The Birmingham Central Library, 1964-74, was a large complex that included the Conservatoire, cited in the Architect’s Journal buildings library http://www.ajbuildingslibrary.co.uk/projects/display/id/2332 accessed 29.10.2017

The library was demolished in 2015/16. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-birmingham-35092981accessed 29.10.2017

Figures 2 and 3 show examples of the fine concrete that made this structure, with the soffits and walls respectively. The building sat on a concrete plane, its pillars were manifest and the walls, externally and internally were all expressed in planes and textures of concrete as was the roof, topping it off. It was an extraordinary expression in the this most versatile medium. Space-Play, in its blog writes “A square set of reinforced concrete columns support the structure, which stands over the ring road and the unfinished bus interchange. The floors are made with precast concrete coffered (waffle) units with a cast concrete surface for reinforcement. The external structure is left bare to expose the concrete work and walls are finished with a locally graded aggregate mix, blasted to give a rough textured surface”. http://www.space-play.co.uk/birmingham-central-library/ accessed 29.10.2017

There was much lament at the decision to obtain immunity to listing in 2009 http://www.birminghamconservationtrust.org/2009/11/23/birmingham-central-library-granted-immunity-from-listing/ accessed 29.10.2017. This paved way for the redevelopment of this part of the city centre and the design and construction of a new library. The demolition became an event and was recorded in the media, as the monster machines gobbled away at the concrete form.

The radical decision to execute caused national interest; in the Independent article, 24 May 2013, Christopher Beanland writes “Buildings bear witness to the tiny dramas that make us human. If we turn concrete to dust, where do those memories go? Madin’s buildings were the backdrops for a million Brummies’ lives – though as time slipped by, they forgot to notice.” He extends his observations, “Brum is an adorable oddball; an eccentric void at the centre of the nation and yet the centre of nothing. Birmingham transforms. Birmingham forgets. Buildings, dreams and memories live in the same unreal world here. Birmingham Central Library is a dreamlike building: Madin’s fantasy made real. Sometimes it’s hard to know where dreams end and reality begins. Paradise Circus boasts a warren of hidden squares, haunted passageways, dead ends” http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/this-britain/the-man-who-built-brum-a-lament-for-the-demise-of-john-madins-brutalist-birmingham-8627547.html accessed 29.10.2017

Perhaps just as ignominious as demolition, is seeing the cloaking in cheap, twenty first century wrappings of noble structures. Here another Madin building actually survives, but becomes smothered with an ignorant and crass veneer of whiteness – http://www.birminghammail.co.uk/news/midlands-news/new-image-shows-major-transformation-10966423 accessed 29.10.2017

O’Flynn in her (undated) blog brings us to the fact that Madin, this man of concrete has an archive that survives to be visited, despite the loss of the structures they laid out. Interestingly she cites Madin’s predecessor and mentor, Sir Herbert Manzoni, Birmingham City Engineer and Surveyor from 1935–1963, “I have never been very certain as to the value of tangible links with the past…” and instead creates a counterpoint herself using the eponymous gardens as her example “Like Manzoni Gardens, the John Madin archive, reminds us that we do not decide, what, if anything might be remembered of us and neither do we decide how, if at all, our lives might be interpreted. We can, though, decide to remember and to interpret. We can make new connections and pathways. We can perhaps choose, as some of our predecessors did not choose, to see the value of tangible links to the past” http://www.catherineoflynn.com/other-writing/why-contribute-to-the-spread-of-ugliness/ accessed 29.10.2017

Work in Progress – Practice Development

My practice is aligning my Pause Project and the continuing image making with the analysis of concrete and the potential to fuse imagery with concrete, making a lament to the past and John Madin in particular. The imagery may be the reappropriation of archive materials interwoven with my own images to create a unique set of works as an installation.

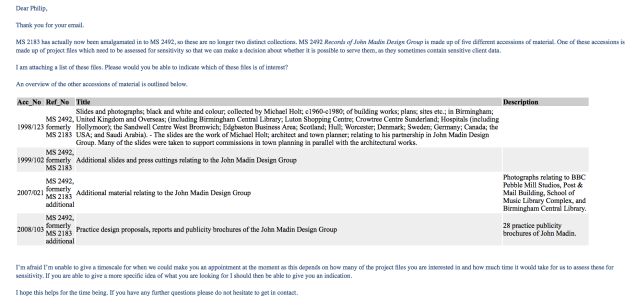

I have arranged to view the Wolfson Archive Centre at the Library of Birmingham with intent to access and review these materials, see figure 5. This endeavour will be recorded via this journal.

fig 1 Photograph Philip Singleton 4th April 2017. Cited as “Birmingham School of Music – 6 storey building – 4 floors for School of music over shopping arcade; Recital room for 250 people; 32 teaching studios; 24 practice studios Paradise Circus, Birmingham Client: Birmingham City Council”

figs 2, 3 Photographs Philip Singleton 20 August 2014

fig 4 Photograph sourced from https://www.expressandstar.com/news/2016/05/26/birmingham-library-demolition-progress-is-just-cracking/

Clawley, A. (2011). John Madin. London: RIBA.

Footnotes

1 A 132 page self published, on line book by Madin fans (which I believe includes his architect son) http://www.john-madin.info/ accessed 29.10.2017

2 Interesting insights into the Madin Library https://inversionlayer.wordpress.com/tag/john-madin/accessed 29.10.2017

ends

Advertisements Share this:

![The Book Thief: 10th Anniversary Edition by [Zusak, Markus]](/ai/466/466.jpg)