One of the ideas informing my dramatisation of the Resnick novel Darkness, Darkness for Nottingham Playhouse was that while we ourselves are alive, the dead – the dead that we know – never quite die. The plot is set in motion by the discovery of the body of a young woman who disappeared during the Miners’ Strike, some thirty years before; what the story then does is revisit the significant moments in that young woman’s – Jenny’s – life, showing them in juxtaposition to the present. To Resnick, who knew her only slightly and is now investigating the circumstances of her death, she was little more than the memory of a bright, lively and outspoken young woman, a firebrand, and during the course of the play he gets to know her more clearly, more roundly, so that, in the scene towards the end [possibly my favourite scene of all], when she visits him in his house where he is getting dressed ready to go to her funeral, it is – bar a quick and instant frisson – no real surprise. She talks to him and he answers, much as he would if she were still alive, much as we hold conversations (inside our heads, more usually, rather than out loud) with those we knew and maybe loved long after they are gone. Much as Resnick, in the play, holds sometimes grudging conversations with the strike leader whose funeral he has attended just before the action opens and who, like a somewhat guilty conscience, comes to haunt him – haunt, the word is correct here, I think – as the play progresses.

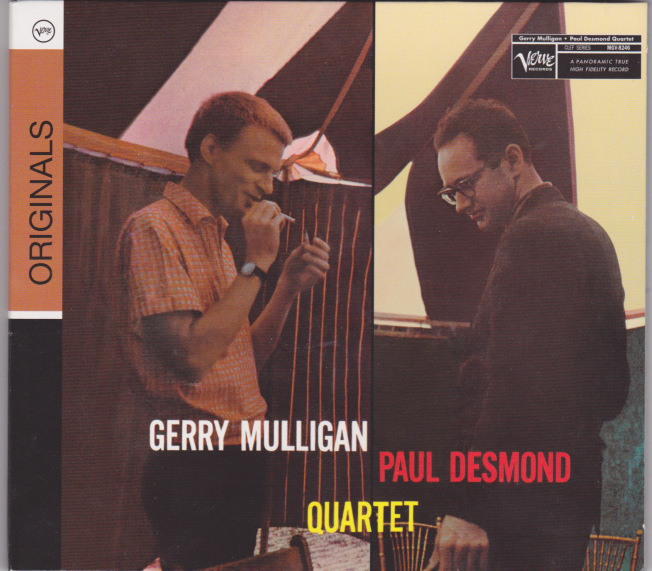

That I’ve been thinking about this at all was not sparked directly by the Playhouse/New Perspectives production of Darkness, Darkness [though it does tend to haunt me, both by what was and, perhaps even more strongly, what later might have been] but by the gift of a CD, a remastering of a session by the Gerry Mulligan/Paul Desmond, originally recorded and released in 1957 and sometimes titled simply Quartet, sometimes Blues in Time.

Listening to it now I am back in the home of my friend Tony Burns, the back bedroom of a house in Finchley, north London, both of us in our late teens; Tony is learning the saxophone – the alto, initially – and I am, less methodically, less seriously, learning to play the drums. Desmond, who plays alto, most usually in the Dave Brubeck Quartet, is probably Tony’s favourite player at this time, though he likes Mulligan too, and, like Mulligan, will play baritone – only finally settling for tenor some good few years later.

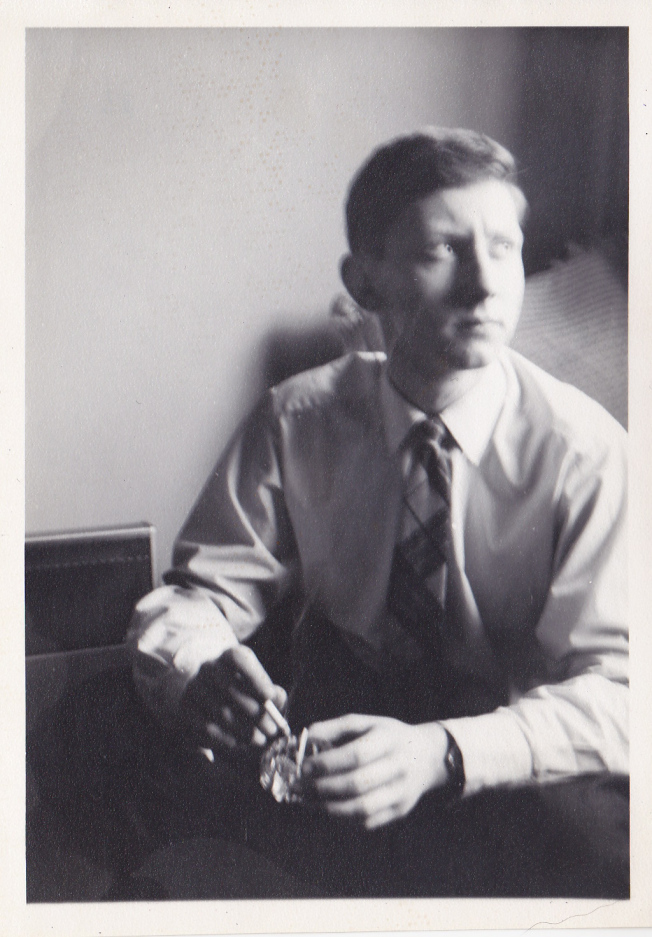

Tony Burns

By profession a tailor, Tony continued to play jazz semi-professionally, only stopping a relatively short time before his death in 2013. By some quirk of circumstance, I was lucky enough, using a borrowed set of drums – my daughter’s – to play with him on a number of occasions in those later years, evening sessions in a pub near the Archway, each one for me a joy. Tony had a way of making you sound better than you really were.

Here, in the final section of a longer poem from Out of Silence called Winter Notebook, are the lines I wrote shortly after Tony died …

My friend, Tony, with whom I first listened,

really listened to jazz, the two of us practising

in his parents’ bedroom, he on saxophone,

me drums, rustling brushes in four-four time

across the top of an old suitcase –

my friend Tony is in a hospice:

the volunteers at the desk welcoming and polite,

all chemo stopped, the carpet deep, the furnishings

not too bright; visiting, we keep our voices low,

talk around you, and just when we think

you’ve drifted off to sleep, you rebuke us

for some mistaken reference to a recording

you know well, Brubeck, perhaps, Mulligan or Getz;

and when Jim retells a joke you first told him

many years before – its punchline too crude

to be repeated here – how marvellous to see

you throw your head back and laugh out loud.For now I sit alone with you and watch you sleep,

breath like brittle plastic breaking inside your chest,

and, for a moment, without feeling I have the right,

reach out and hold your hand.One day soon I will push through the doors,

present myself at the desk, only to hear the news

we know must come. It happens, no matter

what expectations we have, fulfilled or not.

And not dramatically, like some monster

rising from the marsh to seize us, drag us down,

but deftly, quietly, like someone switching out the light.There … you’re gone.

… but not forgotten.

Tony with, to his right, our friend Jim Galvin

Advertisements Share this:

- More