As the Thames path unfurled along the twisting river, so too, I thought, a story would unfurl in my mind, as I soaked up my surroundings. I hadn’t had a writing day in months but had cleared some time and space. Last Monday but one was going to be a good day.

The area stretching up to the South Bank is the part of London I love most and it’s where the characters in my fiction serial for the Londnr hang out. I’d created a post of 1,000 words for each of them, establishing their position at a real moment in time. I knew a bit of back story. I sort of knew what might happen to them.

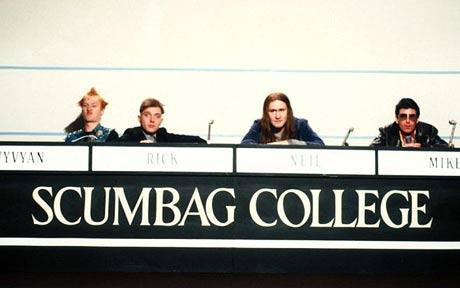

At that point, they were like runners at the start of a race. Or contestants on a quiz show. Poised. Prepared. Anxious and confident.

After that, I didn’t so much as fire a gun but nudged them forward, one at a time, post by post, making notes, here and there. Imagine what I could do with a whole day for writing …

Of course, it didn’t go to plan. I could have followed the river to Richmond and not come up with the big, singular storyline I was hoping for. It felt like a wasted opportunity. That particular Monday was meant to have been something of a heatwave, but that didn’t eventuate, either. (Then came Doris. It was still only February.)

I’d been looking for something that contravened the rules I’d established for the project. (Rules that are obvious only to me, but important nonetheless.) I just hadn’t realised the rules were so binding. Of course, rules are there to be broken but I realised I enjoyed adhering to them.

But who sets the rules, really? Is it the writer? Or the work itself?

I was reminded of Keith Ridgway’s experiences of writing his novel Hawthorn & Child, recounted in an interview with John Self in his blog Asylum, in 2012. I’d loved Ridgway’s earlier work – short stories, a novella and several novels that play with perspective and form. Ridgway never repeats himself but with his latest book, he seemed to take a flying leap to clear everything that preceded it. Even the form of the novel itself.

Ridgway said, ‘I wanted to write a book of fragments. Many small fragments that would be impossible to put together – like a shattered novel in a bag. I didn’t even think of it as a novel, just a book. There were working titles like 78 Pieces Of Shit, and 54 Demonstrable Fictions. At some point it became 38 Marching Songs. Then just Marching Songs. Eventually it became Hawthorn & Child. In all that reduction there was a failure to do what I’d wanted to do. Fragments kept on fitting together, cohering in a really annoying way, wanting to become stories. So I went from 78 to 8. That’s all loss. But the tension between what I wanted and what I was doing became interesting in itself. H&C is, without being, I hope, too maudlin about it, a book about the failure to write a much better, much more interesting book.’

Keith Ridgway

I like his use of the phrase ‘became interesting’, as if this were beyond his control. Will Self used a similar phrase in describing his own process of novel writing which sounds more organised and planned: ‘It’s when I get about two-thirds of the way through that things get interesting, for then I begin rewriting the text from the beginning, even as I’m still working on the end.’ The rules change, and the work changes too. Until that happens, you just have to keep writing.

Is that your experience? Have there been times when a story won’t unfurl as you want it to? Did you end up with something entirely unexpected?

Share this: