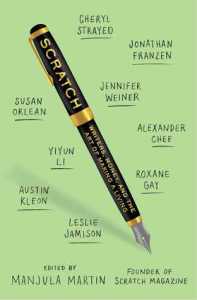

Edited by Manjula Martin

Edited by Manjula Martin

ISBN 978-1-5011-3457-9

“Writing for free looked like work. It felt like work. But it was the illusion of work, a fun house mirror reflection.” –Nina McLaughlin

There are many books about writing as an art form. Library and book store shelves overflow with them. And there are some books about the business of writing, too, such as how to become a freelance writer, or find an agent. But the discussion of writing as an art form predominates, and discussing money remains a bit taboo. In a selection of essays and interview with writers from a variety of fields and at different stages of their careers, Manjula Martin aims to peel back the layers of polite obfuscation and create some transparency about the business and financial aspects of the American writer’s market. Divided into three sections, Scratch takes readers from the “Early Days” of trying to break into the industry, through the “Daily Grind,” of being a working writer, and on to that dreamed of “Someday” when the young writer has finally made it.

In reading this collection, I was struck by the varied and individual business and financial situations faced by the authors. For some writers, the pressure of having to support themselves and their families by writing was crushing. But that same pressure turned others into lean, mean, writing machines. In Malinda Lo’s words, “financial necessity can be extremely clarifying.” In her own contribution to the collection, “The Best Work in Literature,” Manjula Martin writes about how all her non-writing jobs have contributed to her work as a writer. As she puts it, “all this unwriterly work was what allowed me to understand that people and experiences other than mine exist.” On the flip side, in her essay “The Insider,” Kate McKean chronicles how building her career as a literary agent sapped most of her energy for many years, taking her away from her original dream of being a writer. With thirty-three authors included in the collection, Scratch can encompass quite a wide range of the experiences of American writers.

One of the stand-out pieces in the book is “Faith, Hope, and Credit,” featuring a conversation with Cheryl Strayed. Incidentally, it was the online excerpt of this piece that first drew my attention to Scratch. In it, Strayed and Martin discuss what a $100 000 advance ends up looking like in real life, after it is taxed, after the agent takes a portion, and then paid out in four installments. Suddenly $100 000 doesn’t seem like that much money anymore, when parceled out over several years. And even while Wild was hitting and staying on the best seller list, Strayed’s rent check bounced during her promotional tour, because she was just that broke. Wild would eventually make Strayed very comfortable, but when it first became successful, Strayed had already spent the advance paying off the bills she incurred writing the book, but the royalties hadn’t started to come in yet. It is a good reminder that a writer’s financial situation is not always evident from the outside.

Of course, being paid to write can become a sort of insatiable obsession, as documented by Rachel Maddux in her essay “On Staying Hungry.” Many aspiring writers would define having made it as the point where you can live on your writing, but as Maddux points out, the goal posts are always moving. On the experience of finally landing her first cover story, she writes, “I expected to experience a sort of transcendent satisfaction, or at least some palpable sense of leveling up. Instead, my stomach just grumbled, my appetite already recalibrating.” As Alexander Chee puts it in his piece, “there is no ‘made it’ point. There is only ever the making of work.” And there is always more work you could be doing, or chasing. There is always another next level.

The business of becoming a working writer isn’t an easy one, as new writers try to navigate the world of agents, advances, publishing houses, and freelancing. Any agent or editor seems like a good choice for a hungry, unpublished writer, but there are several horror stories and cautionary tales in Scratch about the fatality of the wrong fit. In “Five Years in the Wilderness,” Cari Luna writes about landing an agent for her first novel, which they were ultimately unable to sell. When Luna wrote her second novel, entirely different from the first, her agent didn’t feel that she could represent it, and they parted ways. At the time, this was a crushing blow, but in retrospect, Luna writes, “I see now that it was a very kind thing for my first agent to do, to recognize we weren’t a good editorial fit and set me free. Because I never would have walked away on my own.” Still more sobering is Kiese Laymon’s account of being jerked around by his editor for four years, destroying his health in the process.

Scratch is obviously most useful for, and aimed at, writers, but the main message of transparency and information sharing can be extrapolated to other creative professions. And folks in professions related to writing, such as librarians and book sellers, can definitely benefit from a better understanding of how writers are—or aren’t—being paid. The focus is on traditional revenue streams—publishing houses, magazines, teaching gigs, and speaking tours—but Kickstarter is mentioned in Laura Goode’s piece about funding the independent film she wrote. Self-publishing goes largely unaddressed. Overall, Scratch provides a good idea of the basics of the business of traditional American publishing as it stands today.

__

You might also like MFA vs NYC by Chad Harbach

Advertisements Share this:- Essays

- Non-Fiction

- Writing