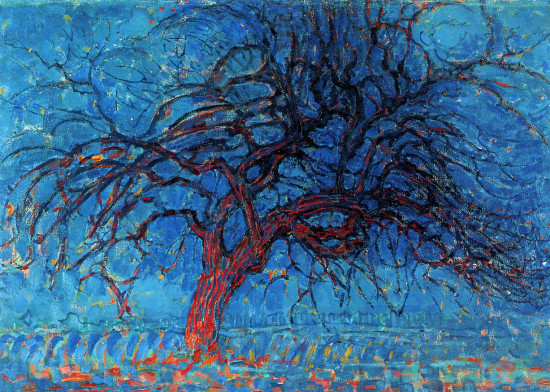

Avond (Evening): The Red Tree, by Piet Mondrian (1908-1910)—I preferred this painting to one of his lozenges.

I compiled a list. Take a moment to guess what these words have in common:

leaven, reticulum, neroli oil, raglan, syzygy, lozenge.

Don’t try too hard, it’s not obvious, other than I liked them, they’re nouns, and they sit in a file together with a few dozen others. That’s it. No deeper insight.

Doesn’t that leave you feeling unsatisfied?

Certainly that’s how I feel, when I’m given a selection off someone’s list, but there isn’t a clear designation of why these words even when they’re supposedly a purposeful sample.

It’s like being given a few answers from a survey, but not being told whether those answers are the best, the worst, the most frequent, the most obscure. In which case you might respond: fine just give me all the data from the survey, I’ll read it myself.

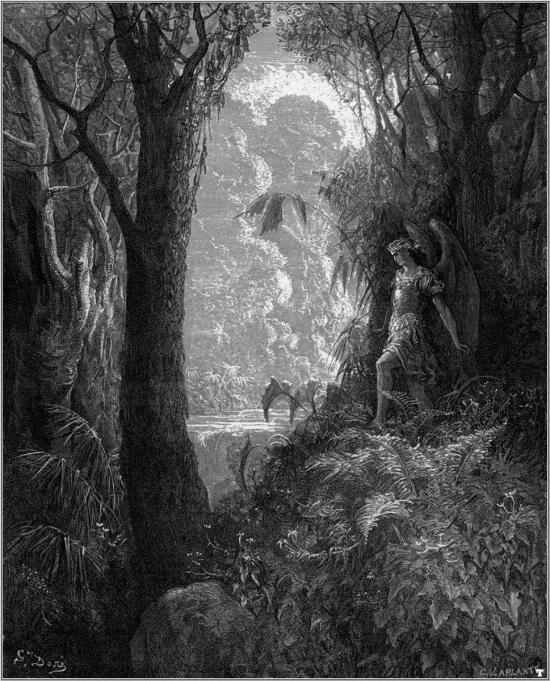

Satan in Paradise by Gustave Dore, illustrating Milton’s Paradise Lost.

One chapter of Mark Forsyth’s Etymologicon presents a selection of words that John Milton (1608–1674) introduced into the English language. The chapter is written in Forsyth’s signature style—bantering, yet erudite—but at one point he simply lets a list speak for itself:

Milton adored inventing words. When he couldn’t find the right term he just made one up: impassive, obtrusive, jubilant, loquacious, unconvincing, Satanic, persona, fragrance, beleaguered, sensuous, undesirable, disregard, damp, criticise, irresponsible, lovelorn, exhilarating, sectarian, unaccountable, incidental, and cooking. All Milton’s. When it came to inventive wording, Milton actually invented the word wording.

Fun! But what to make of the list? Is it ordered alphabetically? No. Are its elements the same parts of speech? No. Are the words related to an obvious subject? No. So what then?

Every form of writing is as much an act of self-expression as it is an act of self-censorship—we must redact most of what we want to say, to express an essence that has the greatest chance of being heard and understood. So why is Forsyth’s list the “essence” of his message that Milton invented words?

Allied with Google, I went to find the complete list.

The internet provides information prodigiously: crossword solutions, rhyming suggestions, reddit answers to the posed questions, Wikipedia articles, the news. Lastly I settled on John Milton – our greatest word-maker, a short article from The Guardian, which didn’t provide a complete list, although it pushed me in the right direction.

According to Gavin Alexander, lecturer in English at Cambridge university and fellow of Milton’s alma mater, Christ’s College, who has trawled the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) for evidence, Milton is responsible for introducing some 630 words to the English language, making him the country’s greatest neologist, ahead of Ben Jonson with 558, John Donne with 342 and Shakespeare with 229. Without the great poet there would be no liturgical, debauchery, besottedly, unhealthily, padlock, dismissive, terrific, embellishing, fragrance, didactic or love-lorn. And certainly no complacency.

The Guardian chose to illustrate Milton’s contribution to English with a different set of words, though both lists agree fragrance was important, and both are clearly enamoured by lovelorn—a rather rare and poetic word.

Lovelorn by Alfred Stevens

Returning to my hunt for a complete list, I asked myself how does one “trawl” a dictionary with 200,000 entries? It turns out quite easily: typing in Milton in the oed.com search field and refining the search to consider only first quotations yields 623 entries. The method isn’t perfect because some words have different meanings and therefore it depends what you count as the first citation. For example, Forsyth includes incidental, where one meaning gives a 1644 Milton citation as the first source, but another gives an earlier citation from someone else in 1616.

These niggling issues aside, I considered my list of 623 Miltonic words. About a fifth, 122 to be precise, fall into the Frequency Bands 4, 5, and 6 of the OED, meaning they occur between 0.1 and 100 words per every million (the list contains no entries from Bands 7 and 8).

All but one of Forsyth’s 21 words comes from amongst those 122. Put differently: he chose from amongst the words he figured most people were likely to recognise and appreciate.

(The exception is lovelorn, that falls under Band 3, which is described as containing words not commonly found in general text types like novels and newspapers, but at the same time they are not overly opaque or obscure. But lovelorn clearly carries enough cachet to be bumped up a Frequency Band or two.)

Now I appreciate the logic behind Forsyth’s choice—and it’s rather obvious in hindsight—but I still wonder: why that set of 20/122 words and not some other?

As to why he didn’t alphabetise his list, I’ll conjecture as follows: patterning symbolises finiteness, while disorder spurs the imagination to expand. Forsyth can’t afford order because he needs the reader to imagine Milton’s contribution to be no smaller than 623.

Perhaps Milton had been aiming for 666.

So that my article, too, isn’t guilty of leaving my readers entirely unsatisfied, here are the 32 most frequent words Milton introduced—Bands 5 and 6—retrieved from the OED according to the method I described. (Although, as I noted above, the method has at least one flaw, and probably many others.)