There is nothing like a walk in solitude, especially should that walk take me to a quiet little stream where I can sit on the banks and just listen: to the sounds of the gentle movement of the water, to the birdsong, to my own breathing and heartbeat, and to my own thoughts. Solitary walks are a gift and a pleasure for this introvert because I am no longer surrounded by people but by sky and clouds and trees and grass and nature: all of which corresponds to my heart. To encounter only the companions of a robin or Monarch Butterfly or the shafts of light coming through the rustling leaves of the trees about me. Sometimes I catch a quick glimpse of a rabbit or fox or lizard or King Snake sleeping on a sun-warmed rock.

To be in nature is to be a poet without ever writing a single word on paper. It is to understand that silence of wildflowers is as lovely as the silence in a European cathedral and, oftentimes, closer to the Creator who delights in such ordinary miracles.

Such walks allow me to contemplate and reflect. To gather my thoughts together as a rainstorm will children dashing in the house from outside.

There is a freedom to walking along the wooded path and among nature. I have deeply cherished these kind of walks ever since I was a boy. All children long to be explorers and adventurers and the woods offer that to them, particularly when I was a boy and could go exploring for hours alone, without parental supervision. It was there that I ate the sweet, juicy wild blackberries and sucked the nectar from the honeysuckle.

These walks allowed me to begin to grasp the truth of John Muir’s writing, “In every walk in nature one receives far more than he seeks.”

For me the woods were as magical as Narnia or Middle Earth. It was especially made so by the fact that in the center of our woods was an old abandoned VW Bug that no one knew how it had gotten there. It was like being Lucy and seeing the lamppost, though I never encountered a faun coming out of the woods or the Volkswagen even once. But that did not matter, the mere presence of this car being there struck a chord in my imagination and filled me thoughts with stories of how and why it was there (always a doorway to another place). Just as C.S. Lewis did when he was a boy, I wrote numerous stories involving animals, who could talk of course, and of their kingdom (comprised of different lands that could be found in the woods that were broken up by fields, the woodlands, the great section of thick Oriental bamboo, the creek, and an area with large boulders that my friends and I climbed on). I drew maps and drawings to go along with such tales.

In her book Wanderlust: A History of Walking, Rebecca Solnit writes about Elizabeth Bennett’s, from Pride and Prejudice, love of solitary walks. Lizzie’s “solitary walks express the independence that literally takes the heroine out of the social sphere of the houses and their inhabitants, into a larger, lonelier world where she is free to think: walking articulates both mental and physical freedom.” For Lizzie to get in touch with her interior, she had to be alone in the exterior world and the best way to do this was walking. It connected her to the earth, her surroundings, nature and, most importantly, herself. Solitary walks were freedom and a place to reflect on identity and relationships to other. Walking was a way of working things out for her.

Like one of my favorite literary heroines, I tend to find not that I necessarily have more thoughts while walking, but that I am more present to them because I don’t have the distractions of technology.

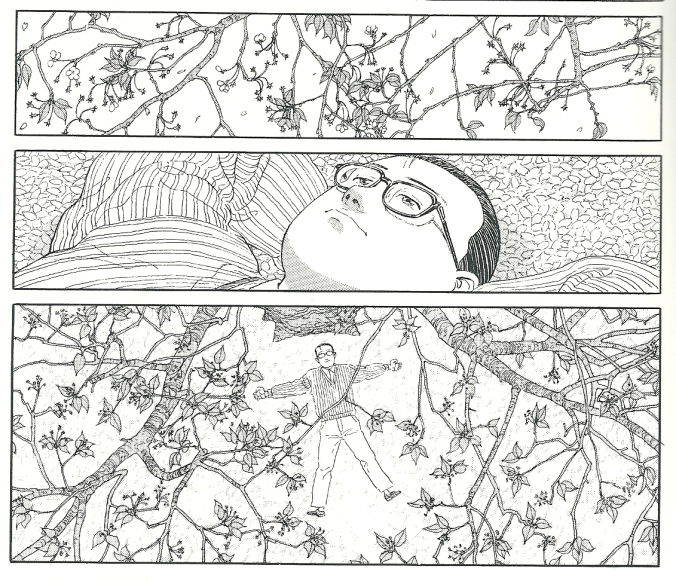

The beauty of walking is not the destination but the act itself. This is something I learned both from my own walks and from the amazingly simple but profound manga The Walking Man by Jiro Taniguchi. There is no narrative other than a nameless man goes for a walk in his neighborhood. He enjoys the pleasures of climbing a tree, observing birds, playing in puddles after a storm, and finding a shell by the beach. He is silent and alone, except for his dog sometimes. It’s a glorious meditation of being present to the life around oneself. Every time that I pause and savor the simplicity of the message of this book, I find my own world expands and grows larger, even if I, like the character, am merely taking a walk in my own neighborhood.

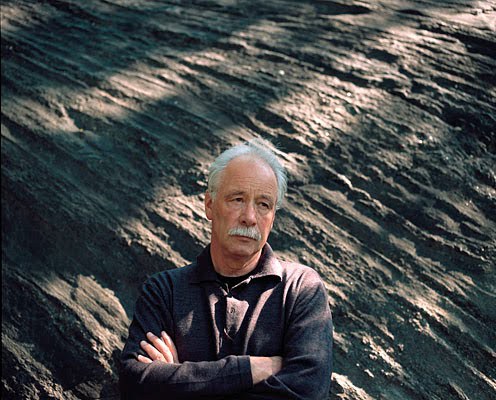

One of my favorite works by the German author W.G. Sebald is his book The Rings of Saturn, which records a walking tour he undertook along the east coast of England. The book is nothing more than a recording of what he came across and the thoughts he had as he walked this pilgrimage. It’s more than a simple recording of facts but a mediation on art, literature, history and place, as well as reflecting on memory. Of this, he writes, “Memories lie slumbering within us for months and years, quietly proliferating, until they are woken by some trifle and in some strange way blind us to life.” This walk, for Sebald, is a way of noticing more than his surroundings, but also myth, memoir, travelogue, and history written in the most haunting of prose. As a German in England, it was also about understanding identity in a foreign place.

After having read this book, I noticed that I began to wonder about personal and cultural memory being revealed in my own walks. As I noticed buildings in the small town where we live, I began to wonder of their own history and to research about it, in a sense to gain a better understanding of place. I began to view myself within that context and to ask, “What does that mean?”

For me, walking is not just mere exercise, as I see so many others undertaking it as, but as a time for deeper reflection. My walks are to be in that place in both body and spirit. To be open and aware of my surroundings and what it has to offer, to allow the path I undertake to nourish my soul in a way that cannot be done anywhere else or by any other means. As Henry David Thoreau wrote, “I think I cannot preserve my health and spirits, unless I spend . . . hours a day . . . sauntering through the woods and over the hills and fields, absolutely free from all worldly engagements.”

It is to return to the joy of walking that I experienced as a child. Though I was often a lonely boy, I never felt so whenever I was in the woods. Then I was not lonely, but solitary. Loneliness takes away peace, but solitude returns it tenfold. In my head, I become William Wordsworth or Mary Oliver or Henry David Thoreau or Annie Dillard or John Muir. It is a withdrawing from society to the soul to the place where I encountered God, long before I encountered God in a church.

No matter what the weather, I know I’m alive when I am walking. To know that, beneath each step, is the round arc of the world. Like those I’ve mentioned, when I walk I explore the mind and the terrain. My walks offer up new thoughts, new experiences, new encounters, new explorations. And it reminds me again and again, that the world is much bigger and more wondrous than I can ever begin to imagine. When I walk, I do so with the understanding that I cannot and should not own such beauty or such moments, for I am only a sojourner who is grateful for the inexhaustible pleasure that my walks give me.

Nature is always an invitation to discover; not an acquiring of more knowledge, but is, in itself, a means of knowing. There is always something awakening within me that wish only to hear the sound of wind in the verdant trees and the gurgling waters of a stream and to know that this is what it means to be thoroughly awake and alive to the surprise and the truth of the world: that grace is all around to those who are present to receive it.

Advertisements Share this: