I have always liked puzzles. There are few things that give me more satisfaction than putting my mind to a problem and solving it. A good description connects this to our relationship with pain.

Puzzle, game or puzzle game?People solve puzzles because they like pain, and they like being released from pain, and they like most of all that they find within themselves the power to release themselves from their own pain.” – Mike Selinker and Thomas Snyder, Puzzle Craft: The Ultimate Guide on How to Construct Every Kind of Puzzle1

Puzzle games, then, seem like a natural fit for my interests. It is true that most (if not all) games contain elements of puzzle solving, or process thinking, which makes games inherently satisfying. But while I’ve grown up solving puzzles like crosswords and Rubik’s cubes, I wouldn’t consider them games. The concepts of puzzle and game have some key differences that make puzzle games tricky to design.

In a few ways, puzzles don’t actually behave like games. They are problems, that when solved, don’t often have fun replayability in the same way that most games do. Solving a riddle or a math problem is only really satisfying the first time, while puzzles that are included in games can often be dynamic because of changing game states, altered by the game environment itself (e.g. which way the monsters are chasing you in Pac-Man provides a puzzle of how to get away), or by other players in multiplayer settings (e.g. an opponent’s chess moves affects the board and creates a new puzzle of how to make your next move).

Puzzles have two states: they are either solved or unsolved. This means that games based around puzzles have specific gateways that players need to pass through by turning unsolved puzzles into solved ones. However, this is problematic for the one reason that puzzles can sometimes require such a shift in perception or a twist in thinking for the player that no matter how hard you try, there is no way to make that cognitive leap. We all know this feeling from being given the answer to a riddle and knowing that we would have never guessed it.

No matter how well-designed, no matter how many hints are given, no matter how simple they seem, some puzzles are going to remain unsolvable, not to all players, but to at least one player out there. The more difficult or heavily designed the puzzles are, the higher the number of players who will feel lost, or frustrated, because they aren’t thinking exactly the way the game designers meant. If players aren’t facing the correct direction, they won’t catch a glimpse of the answer in the distance, or be able to follow the carefully constructed trail of breadcrumb hints to the solution.

Being stuck in a problem without seeing the way out is very frustrating, and it’s the opposite of how you want your players to feel. Players want to feel, as Selinker and Snyder said, that they have the power within themselves to overcome the challenge, the insight or knowledge or wit that allows them to come to the correct conclusion on their own. As game designers, we should want to give players something challenging, but something they can get through, not something impossible. But we often fail to handle the impossibility of puzzles, maybe because we cannot imagine from our side of things that the solution could be out of reach to someone who does not have the same prior knowledge or the same way of thinking as we do.

Being stuck in a game is no funI spent a nine hour train ride from New York to Pittsburgh playing Double Fine’s Broken Age, a game that I’d been excited to play since I saw Double Fine’s documentary about the process of making that game. The point-and-click adventure seemed like the ideal game for a long train ride, so I downloaded both acts on to my computer for the journey. I sped through Act One, and though I didn’t find the puzzles particularly challenging, I enjoyed the game for its art and storytelling. Old-school puzzle adventures have a reputation for puzzles that are solvable by brute force (as in, try every single object at every single interaction point, or try every single dialogue line with every single character, and eventually you’ll arrive at the solution), but in my mind, that’s part of their charm, and the gorgeous art and humour more than made up for some of the puzzles being rote. Feedback to Double Fine between Act One and Act Two being released said that the puzzles were too easy, and correspondingly, I noticed a significant increase in difficulty when I attempted Act Two on that train ride.

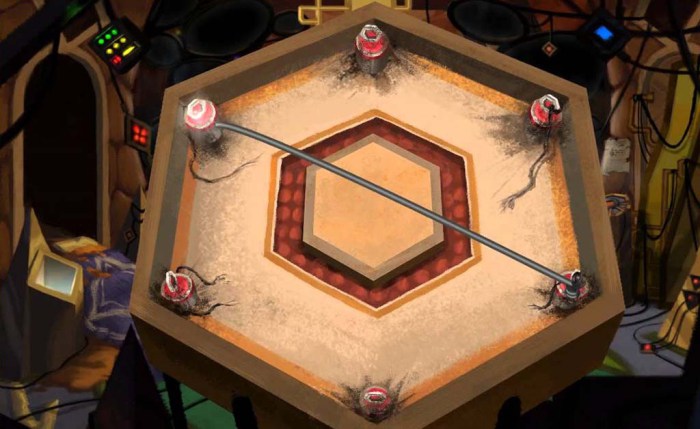

For example, there’s one puzzle that requires the player to notice symbols in a small photograph while playing as Vella and apply that knowledge to solve a puzzle while playing as Shay. I struggled with even realising that I needed to find a clue for Shay somewhere on the ship, to know what information would be helpful, and to think that the key would be presented pictorially in a photograph – all this together would have been a leap that I could not have made on my own. In a world where walkthroughs for every conceivable game are available online, my frustration was quickly allayed by a quick Google search, but it was replaced with something more dissatisfying: a feeling of guilt that I had cheated and disappointment in not having been able to solve the puzzle by myself, that somehow I was not clever enough to find the clue in game or make the connection in my head.

The answer Shay’s tricky wiring puzzle is located far away, in the background of a photograph on the ship that you have to play as Vella to see. |

|

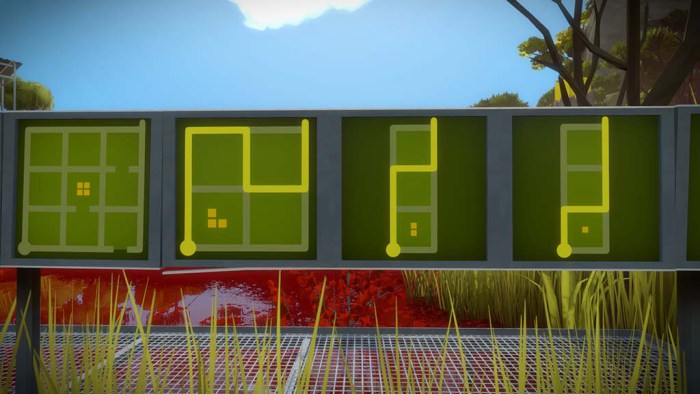

This happens to me again and again, in games like Portal, the Nancy Drew point-and-click adventure games I played as a kid, and more recently The Witness, where some puzzles I encountered near the beginning frustrated me so much that I ended up quitting the game. While Portal is designed more linearly, allowing players to build up a knowledge base that increases in complexity as the puzzles get gradually more difficult, The Witness just drops you on the fully open island world, allowing access to many puzzles that are too complex for the beginner player just getting their bearings. At one point, I got a moving platform to move me to the other side of a lake, then couldn’t fathom how to solve the puzzles on the other side. I didn’t know you could move the platform back, so feeling too stuck and being unwilling to “cheat” by looking it up online, I gave up on the game entirely.

In-game hints are not enoughA strategy many game developers use to address this is providing hints in the game to help nudge players towards the answer. There are several problems with these hints:

That said, the idea that addressing the problem of the stumped player should be handled in-game seems appropriate. If done well, it keeps the player immersed in the game world, and prevents the player from having to go to outside sources to find the answer.

MSN Games’ description of the hint button says it all: “Can’t see a next move? Click the HINT button for help. You won’t lose points … maybe just a little pride.”

The best hints are not leading clues but actually reveals of a solution, like the one in Bejeweled, which immediately reveals the next step, or the available move that the player does not see, and immediately allows the player to move forward. I like the way hints are described in Forest Home, “Tap the hint button to complete a move”, because it indicates that the hint actually finishes a part of the puzzle for you, and is in a sense the answer to a mini-problem rather than a nudging towards one that may not be helpful. These are answers disguised as hints, and the best part is that because they are answers, they are guaranteed to unblock stuck players and move them to the next puzzle.

|

|

In any case, asking for a hint or an answer does not feel great, it’s like giving up on a really tough riddle.

A call for in-game solutionsMy favourite way to handle impossible puzzles is the simplest of them all, but maybe the most counter-intuitive. Game designers should simply start giving away the answers to their puzzles in game. Jesse Schell discusses this in his book The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses, claiming that the experience of a pleasurable moment when you’ve solved a puzzle is triggered not by solving the puzzle but by seeing the answer2.

Think about mystery novels – they are just big puzzles in book form. And sometimes readers guess the ending ahead of time, but more often, they are surprised (Oh! The butler did it! I see it now!), which is just as pleasurable, and weirdly, more pleasurable than if they had figured it out themselves.” – Jesse Schell, The Art of Game Design: A Book of Lenses

I think there’s more to it than that, because obviously, we don’t want to start telling players how to finish our games before they’ve had a chance to think. But in-game metrics can tell designers if there’s a player who’s spent a lot of time going through the same motions without progressing, maybe talking to all the characters multiple times, or repeating the same actions, or trying to trial and error a puzzle that requires additional information. A little added work implementing an invisible feature that allows game designers to decide when it’s appropriate to offer, gently and within the game world, the solution to a puzzle, would make a world of difference to a player that is truly stuck.

For example, if in Broken Age, I had seen the photograph as Vella, but was not able to make the connection with Shay’s puzzle of rewiring his Hexipal, Vella could have said something like, “Hey, that’s an interesting picture. Those diagrams in the background, they look like something Shay and his family might have used to wire circuits in instruments on the ship.” Or maybe Shay could have asked me to look on the ship for that specific photo because it contained important information about Hexipals. Even though this doesn’t give away the whole answer, it would have let me know that the diagrams were important, and related to Shay’s side of the puzzle. Once I brought that knowledge over to Shay, if I was still stuck there, he could have told me exactly how to use the diagrams. Either way, it would have allowed me to come to the answer on my own or receive the answer in a way that was in keeping with the game world.

More overtly, in The Witness, when there was a row of puzzles aimed to help me learn a certain mechanic, if I had been stuck for a long time, I would have liked to have seen the answers outright. By showing the complete solution to one of these puzzles, it would have helped me develop intuition for and understand the rules of the puzzles better, and would potentially allow me to solve more difficult puzzles to progress further in the game. Because our brains work by following examples from previous experiences, nothing is quite as helpful to solving problems as having seen the solution to a similar problem in the past. When there were never-before-seen puzzles in The Witness, I was stuck because my brain’s model of those sort of puzzles was either missing or incomplete, so seeing just one solution could have helped immensely.

The Witness is filled with rows of puzzles like these, designed to introduce players to new concepts. But more than once, I was stumped even at the first puzzle, and would have liked to have seen the answer as an example for future similar puzzles, in order to build that knowledge.

Player ego > designer egoWhy does it matter, if these solutions are available online anyway, and stumped players who want to continue playing a game will look them up? Providing the answer in-game does a couple of subtle things: it rewards the player for perseverance, and makes them feel good. It makes the player feel that the game was designed with the intention of this happening, and that they were indeed smart enough to arrive at a solution in the game, however it was provided. Heck, if designed well enough, the player might not even realise that the game is providing the answer. Players have egos, and making a player feel good for seeing the answer, as Jesse put it, can be done so much better in the game itself than having them search online for a seemingly better player’s tutorial or walkthrough.

I don’t think providing the answer compromises a game’s puzzle integrity, because considering how players feel should not be secondary to our game designer egos of making the toughest, most mind-bending puzzles ever. Game designers should consider the player first, and how the player feels should far outweigh whatever lofty goal the puzzle design had. Providing the answer will bring the player to that conclusion anyway, and give the player that “aha” moment for having seen the answer without dragging in feelings of guilt, frustration, and self-doubt from having had to “look up the solution online”. The flip side is having many players quit the game completely without finishing it.

Monument Valley is a puzzle game that became very popular, despite how easy it was to complete puzzles.

Games like Monument Valley prove that popular games do not have to contain the most challenging puzzles. The game received favourable reviews across the board and continues to have a 4.7 rating on Google Play and a 4.5 rating on the App Store, but is known for being really easy. A few of my friends have said that Monument Valley‘s gameplay was so easy that it wasn’t enjoyable, but the ratings and reviews indicate that games of this sort that allow players to come to correct solutions and progress quickly (thus presumably making players feel proud in their puzzle-solving ability and good about themselves) are popular in their own right.

Our role as designers of puzzle games should be to give the players ample tools to solve our puzzles, however impossible they may be. And if that means designing a way to provide the answer in-game to give players the experience of feeling like they are the hero and that they did it, I’m all for it.

References Cited