You’ve heard of having mild autism? It’s a ‘kind’ way of describing someone as almost not autistic but nearly normal. Well, we won’t have it, so how about a t-shirt with the slogan ‘Spicy autism’ instead? Can you take it?

Monday night’s event for Book Week Scotland at Waterstones was like coming home, where I was surrounded by like-minded people, and they were clever and amusing and weird enough that they appeared normal [to me]. It was great. And we need more of this.

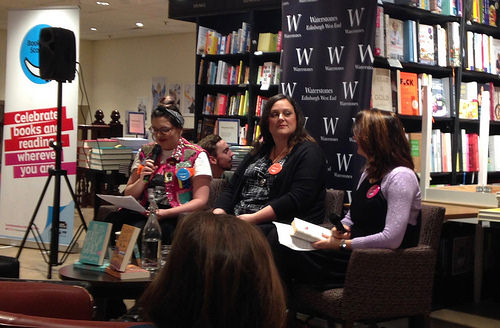

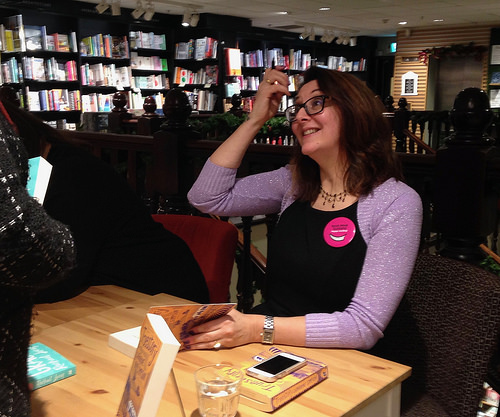

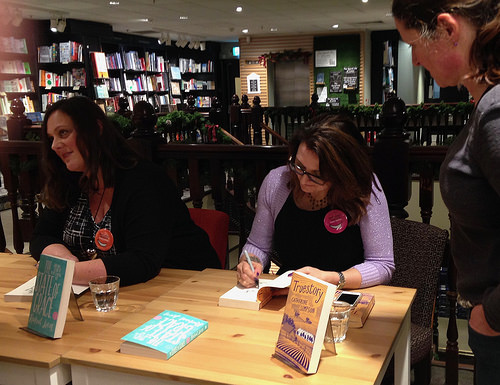

The conversation between Rachael Lucas, who wrote The State of Grace about a teenage girl with Asperger Syndrome, and Catherine Simpson, whose adult novel Truestory features a boy with Asperger’s, was chaired by Catherine’s daughter Nina. I can’t think of a better combination of people to listen to on this subject.

It was Nina’s first experience of chairing, and her straightforward style and intelligence was just what was needed. When she was younger she caused Catherine much worry, mainly because neither the health service nor the education authorities were helpful or sympathetic. (I’ve been there. I know.) And there was one thing Catherine told us, which was uncannily close to what I’ve felt myself.

Rachael had spent a lot of time pointing out her daughter was unusual, but it still took ages for a diagnosis, for both of them. As is often the case; if one family member is diagnosed, another might be next.

With such interesting lives to discuss, I had very little need to hear [the usual] details about their books. It’s their lives we really wanted to hear about. This doesn’t mean that books about aspies are not needed, because they are. People like to find themselves in books.

‘Coming out’ as an aspie when you write a book about it, was both necessary and difficult for Rachael. Her daughter’s autism was not recognised because she didn’t line up her toys, and because Rachael helped her in trying to be normal. That in itself seems to be a sign of being on the autistic spectrum.

Catherine needed something to do when she was stuck at home because of Nina, and eventually hit on writing, and did a course at Napier, before writing her novel which among other things features the f-word (as she discovered when starting to read to us), and growing cannabis. (It sounded much funnier when she said it. I suspect you need the book.)

Rachael decided to write about a teenage girl, partly because she had one herself, but also because everything people know about autism tends to be about boys. On the other hand, Catherine wrote about a boy, so people wouldn’t assume it was about Nina, but she regrets this now. And anyway, Nina has often been described as masculine, which is another situation I recognise. You can still love My Little Pony. And Doctor Who.

One side-effect after reading Grace has been that some people have got their own diagnosis, which both writers agreed was excellent, but they also pointed out quite how hard this can be to achieve. The internet is mostly for the good, and it suits autistic people well. You can pause your life briefly when online, and take a moment or two to think about how to respond to what someone has said. (Rachael aptly called this her ‘buffering.’)

And you don’t have to smile to look friendly (Rachael’s husband asked her what she was doing, and when she said she was trying to avoid looking scary by practising smiling, he asked her to please stop). Nor do you need to worry about eye-contact online.

These two women are funny. But it seems their books have too much of a happy ending. Autistic people are only ever allowed to be ‘tragic and inspirational.’ Happy is for neurotypicals. But when you’ve had your mothering skills questioned by (possibly well-meaning) staff at your child’s school, then you are surely permitted to rebel? “Have you tried the naughty step?’

Looking at how Nina turned out, I’d say Catherine did as much right as any parent. And I’m sure the same goes for Rachael’s daughter [who wasn’t present]. There were lots of questions from the audience, but in case there hadn’t been, Nina was prepared with more of her own, as any good aspie would be.

Lists’r’us.

And yes, balloons are frightening things. The Bookwitch family has at least one member who always tenses up, in case a balloon will pop unexpectedly.

Advertisements Related