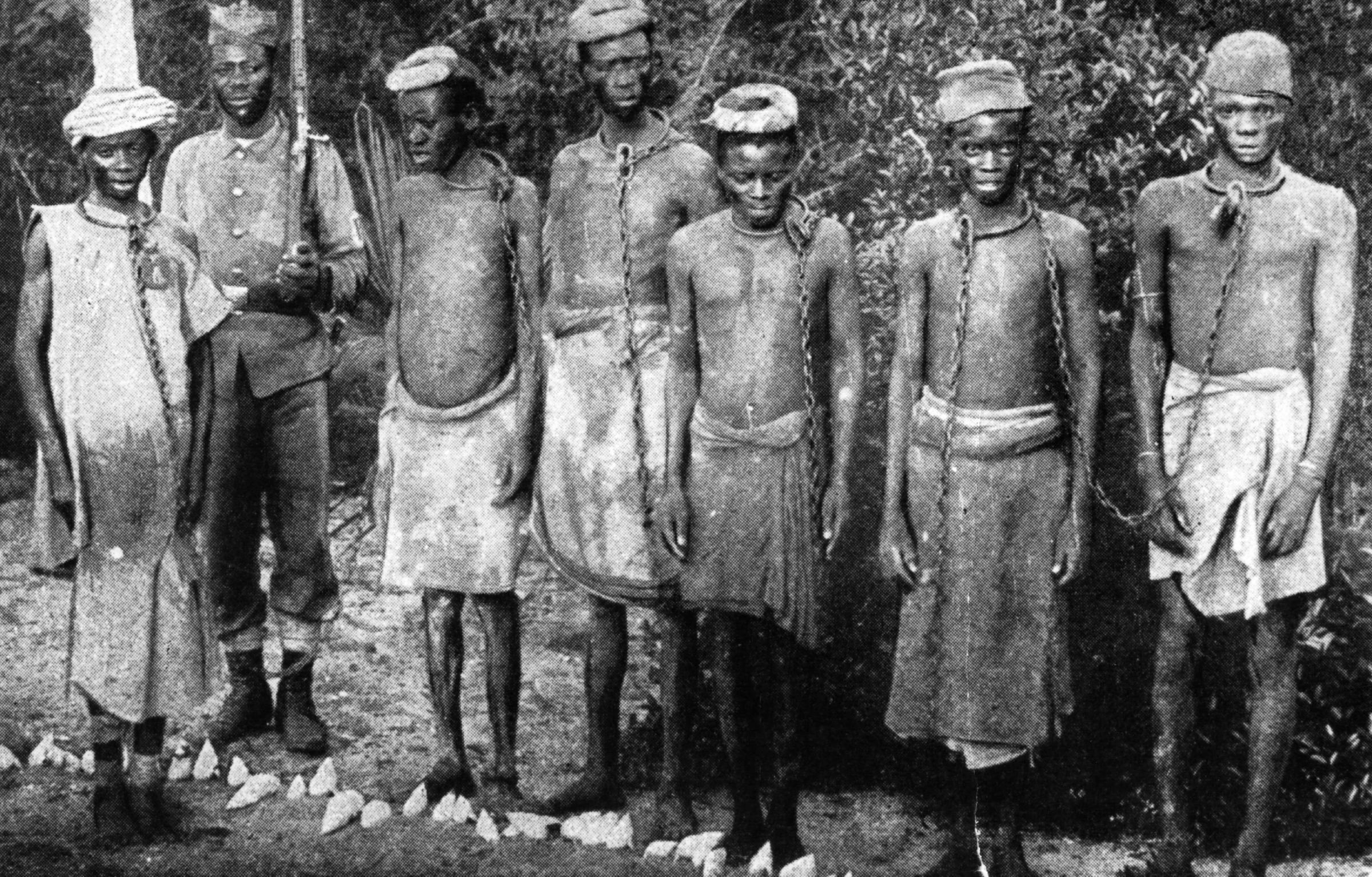

Sugar Money is narrated by Lucien, a teenage slave Photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

FOR her third novel, Jane Harris takes an obscure true story and turns it into a gripping tale of colonial cruelty set in the Western Antilles in the late 18th century. Enthrallingly narrated by Lucien, a teenage slave, the story begins in Martinique and travels to Grenada where the British have instituted a particularly brutal regime for the enslaved. Harris has said she that visited Grenada during her research and the evidence of this is abundantly plain in the sense of place and time she evokes.

Lucien and his older brother, Emile, live on Martinique, slaves of les Frères de la Charité, a French religious order running a hospital on the island. In order to keep the hospital afloat, the Fathers have indigo and sugar cane plantations, tended by their slaves. By the standards of the age, the Fathers are not particularly harsh towards their charges, but the slaves live in primitive conditions and have no say in their fate. They can be bought, sold, or rented out in order to generate more money for the hospital.

In 1742, the Fathers had been drafted in by the French Colonial Government to run a hospital in Fort Royal, in neighbouring Grenada. When the superior Father died, the government took over the running of the hospital once again and sent the Fathers back to Martinique, but made them leave their slaves behind. In 1763, the British invaded Grenada and took over the hospital and the slaves, subjecting them to a vicious regime with ferociously harsh punishments for the slightest infraction.

Father Cléophas wants the slaves brought to Martinique, and decides that Emile and Lucien should go to Grenada covertly and persuade the slaves to escape from their British masters. For Lucien, it seems like a grand adventure but the more experienced Emile realises how much danger they are placing themselves in. Father Cléophas knows that Emile is desperate to see Céleste, the woman he loves, and despite his misgivings, Emile will do his best to bring Céleste to the relative safety of Martinique.

The relationship between the brothers forms the heart of Harris’s story and even as they bicker, the bond between them remains strong. When the illiterate Emile struggles to read a parchment that Father Cléophas has given him, Lucien empathises. “A pang seized my heart as I watched him squint at that page.” Lucien often feels that Emile is trying to side-line him and claim any glory for himself when, in fact, Emile is trying to protect his young brother. Lucien’s childish need to prove himself a man leads to trouble for both, but he remains likeable and sympathetic throughout.

Language plays an important role in the story. Lucien is sent on the secret mission because he speaks some English which may prove useful if the brothers are stopped by British soldiers. The French refer to the British as “the Goddams”, and their slaves speak a mixture of pidgin French, English and Kréyòl, forming a colourful patois. There is a pleasing rhythm to the slaves’ vivid and descriptive dialogue. France becomes “Fwance”, “kickeraboo”means dead, and “Chyen pa ka fè chat” means “dogs don’t make cats”. “Mwen ni bel poisons!” shout the vendors at the St Pierre harbour market where Lucien has often tried to buy fish or other goods, “paying in sugar, tomorrow self”.

Harris does not shy away from the horrendous conditions slaves are forced to endure, and the punishments meted out. Lucien, barely in his teens, already has a “back ridged with an island of scars, a map of tyranny,” thanks to Pillon, the violent man who fathered him. On Grenada, the brothers see a slave standing naked all day in the sun and trying not to let his ear, which is nailed to a wall, rip open. The callous inventiveness of the Goddams’ punishments is horrifying. Filling a slave’s mouth with human excrement and sealing it shut for several hours is one of their more disgusting methods. Although the Goddams are often referred to as English, there are Scots running plantations and overseeing the slaves. It is subtle, but Harris demonstrates that Scots were deeply involved in slavery.

This is a novel that celebrates the incredible capacity of humans to pursue lives filled with love and courage in the face of overwhelming cruelty. Harris’s novel may be set some 250 years ago, but it has a key relevance to the modern slavery that still blights our world.

Sugar Money by Jane Harris is published by Faber & Faber, priced £14.99

Advertisements Share this: