Great Britain – Scott #231 (1936)

On December 11, 1936, Edward VIII’s abdication, removing himself as King of the United Kingdom and the Dominions of the British Empire as well as Emperor of India, was given effect by Act of Parliament: His Majesty’s Declaration of Abdication Act 1936. He had signed the instruments of abdication the day before at Fort Belvedere, a country house on Shrubs Hill in Windsor Great Park, in Surrey, England constructed in a Gothic Revival style in the 1820s. The formal abdication was witnessed by his three younger brothers: Prince Albert, Duke of York (who succeeded Edward as George VI); Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester; and Prince George, Duke of Kent. Edward VIII had ruled only since January 20, 1936.

Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David Edward was the eldest son of George V and Mary of Teck. He was named Prince of Wales on his sixteenth birthday, nine weeks after his father succeeded as king. As a young man, he served in the British Army during the First World War and undertook several overseas tours on behalf of his father.

Edward became king on his father’s death in early 1936. However, he showed impatience with court protocol, and caused concern among politicians by his apparent disregard for established constitutional conventions. Only months into his reign, he caused a constitutional crisis by proposing marriage to Wallis Simpson, an American who had divorced her first husband and was seeking a divorce from her second. The prime ministers of the United Kingdom and the Dominions opposed the marriage, arguing that a divorced woman with two living ex-husbands was politically and socially unacceptable as a prospective queen consort. Additionally, such a marriage would have conflicted with Edward’s status as the titular head of the Church of England, which at the time disapproved of remarriage after divorce if a former spouse was still alive. Edward knew that the British government, led by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, would resign if the marriage went ahead, which could have forced a general election and would ruin his status as a politically neutral constitutional monarch. When it became apparent that he could not marry Wallis and remain on the throne, Edward abdicated. He was succeeded by his younger brother, George VI. With a reign of 326 days, Edward is one of the shortest-reigning monarchs in British history.

After his abdication, he was created Duke of Windsor. He married Wallis in France on June 3, 1937, after her second divorce became final. Later that year, the couple toured Germany. During the Second World War, he was at first stationed with the British Military Mission to France but, after private accusations that he held Nazi sympathies, he was appointed Governor of the Bahamas. After the war, Edward spent the rest of his life in retirement in France.

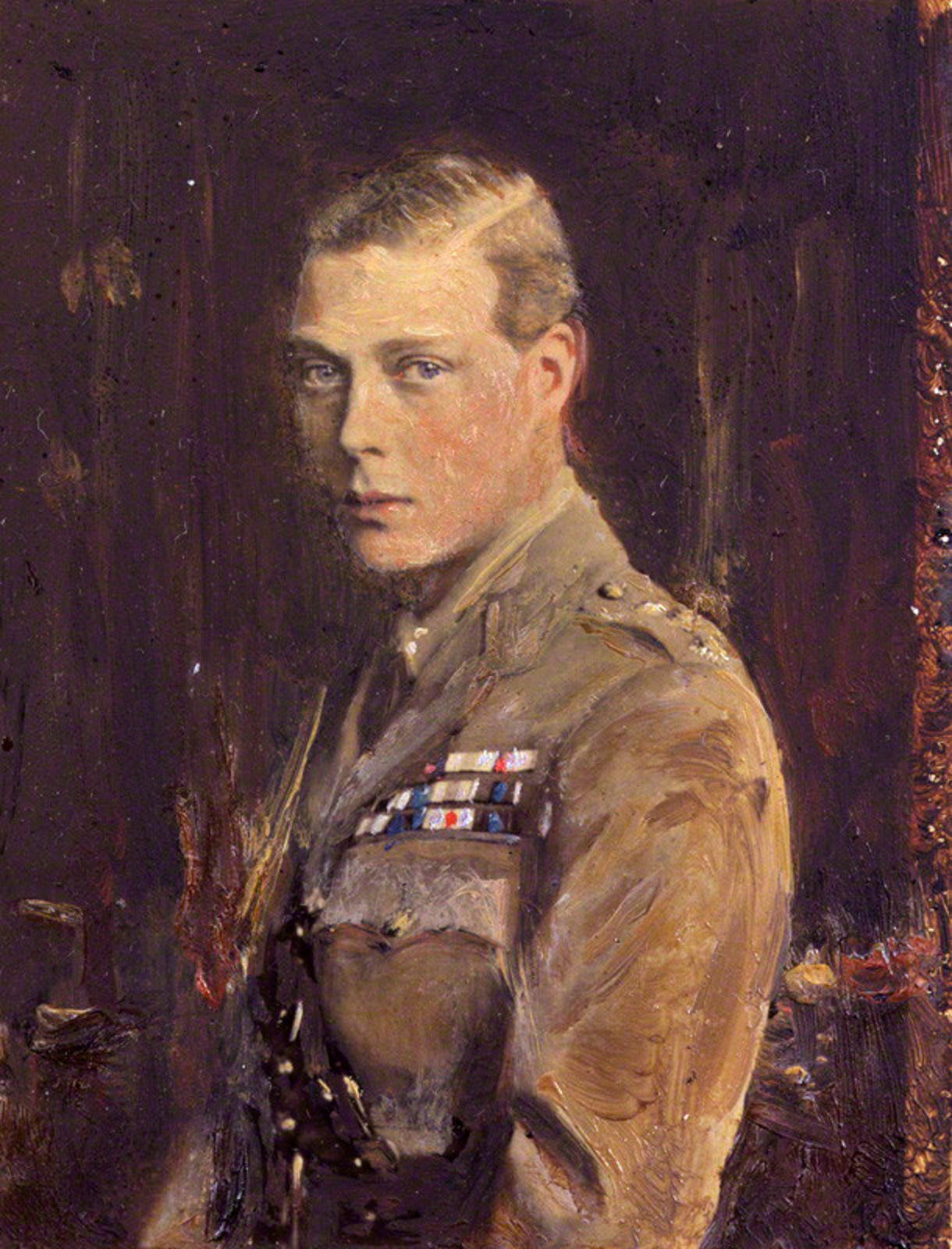

Edward in 1936

Edward was born on June 23, 1894, at White Lodge, Richmond Park, on the outskirts of London during the reign of his great-grandmother Queen Victoria. He was the eldest son of the Duke and Duchess of York (later King George V and Queen Mary). His father was the son of the Prince and Princess of Wales (later King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra). His mother was the eldest daughter of the Duke and Duchess of Teck (Francis and Mary Adelaide). At the time of his birth, he was third in the line of succession to the throne, behind his grandfather and father.

He was baptised Edward Albert Christian George Andrew Patrick David in the Green Drawing Room of White Lodge on July 16, 1894, by Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury. The names were chosen in honour of Edward’s late uncle, who was known to his family as “Eddy” or Edward, and his great-grandfather King Christian IX of Denmark. The name Albert was included at the behest of Queen Victoria for her late husband Albert, Prince Consort, and the last four names — George, Andrrw, Patrick, and David — came from the Patron Saints of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. He was always known to his family and close friends by his last given name, David.

Edward (second from left) with his father –Gworge, Duke of York — and younger siblings (Albert and Mary), photograph by his grandmother Alexandra, 1899.

As was common practice with upper-class children of the time, Edward and his younger siblings were brought up by nannies rather than directly by their parents. One of Edward’s early nannies often abused him by pinching him before he was due to be presented to his parents. His subsequent crying and wailing would lead the Duke and Duchess to send him and the nanny away. The nanny was discharged after her mistreatment of the children was discovered.

Edward’s father, though a harsh disciplinarian, was demonstrably affectionate, and his mother displayed a frolicsome side with her children that belied her austere public image. She was amused by the children making tadpoles on toast for their French master, and encouraged them to confide in her.

Initially, Edward was tutored at home by Helen Bricka. When his parents travelled the British Empire for almost nine months following the death of Queen Victoria in 1901, young Edward and his siblings stayed in Britain with their grandparents, Queen Alexandra and King Edward VII, who showered their grandchildren with affection. Upon his parents’ return, Edward was placed under the care of two men, Frederick Finch and Henry Hansell, who virtually brought up Edward and his brothers and sister for their remaining nursery years.

Photograph of HRH Edward Prince of Wales, standing with a terrier in front of a 9.2 inch gun on board HMS Hindustan, 1910.

Edward was kept under the strict tutorship of Hansell until almost thirteen years old. Private tutors taught him German and French. Edward took the examination to enter Osborne Naval College, and began there in 1907. Hansell had wanted Edward to enter school earlier, but the prince’s father had disagreed. Following two years at Osborne College, which he did not enjoy, Edward moved on to the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth. A course of two years, followed by entry into the Royal Navy, was planned. A bout of mumps may have made him infertile.

Edward automatically became Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay on May 6, 1910, when his father ascended the throne as George V on the death of Edward VII. He was created Prince of Wales and Earl of Chester a month later on June 23, 1910, his 16th birthday. Preparations for his future as king began in earnest. He was withdrawn from his naval course before his formal graduation, served as midshipman for three months aboard the battleship Hindustan then immediately entered Magdalen College, Oxford, for which, in the opinion of his biographers, he was underprepared intellectually. A keen horseman, he learned how to play polo with the university club. He left Oxford after eight terms, without any academic qualifications.

Edward was officially invested as Prince of Wales in a special ceremony at Caernarfon Castle on July 13, 1911. The investiture took place in Wales, at the instigation of the Welsh politician David Lloyd George, Constable of the Castle and Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Liberal government. Lloyd George invented a rather fanciful ceremony in the style of a Welsh pageant, and coached Edward to speak a few words in Welsh.

Portrait of Edward by Reginald Grenville Eves, circa 1920.

When the First World War broke out in 1914, Edward had reached the minimum age for active service and was keen to participate. He had joined the Grenadier Guards in June 1914, and although Edward was willing to serve on the front lines, Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener refused to allow it, citing the immense harm that would occur if the heir to the throne were captured by the enemy.

Despite this, Edward witnessed trench warfare first-hand and visited the front line as often as he could, for which he was awarded the Military Cross in 1916. His role in the war, although limited, made him popular among veterans of the conflict. Edward undertook his first military flight in 1918, and later gained a pilot’s licence.

The Prince of Wales at the Front in Merville, France, August 8, 1915.

Edward’s youngest brother, Prince John, died at the age of 13 on January 18, 1919, after a severe seizure. John suffered from epilepsy, and Edward, who was 11 years older than his brother and had hardly known him, saw his death as “little more than a regrettable nuisance”. He wrote to his mistress of the time that “[he had] told [her] all about that little brother, and how he was an epileptic. [John]’s been practically shut up for the last two years anyhow, so no one has ever seen him except the family, and then only once or twice a year. This poor boy had become more of an animal than anything else.” He also wrote an insensitive letter to Queen Mary, which has since been lost. She did not reply, but he felt compelled to write her an apology, in which he stated: “I feel such a cold hearted and unsympathetic swine for writing all that I did … No one can realize more than you how little poor Johnnie meant to me who hardly knew him … I feel so much for you, darling Mama, who was his mother.”

Throughout the 1920s, Edward, as Prince of Wales, represented his father, King George V, at home and abroad on many occasions. His rank, travels, good looks, and unmarried status gained him much public attention, and at the height of his popularity, he was the most photographed celebrity of his time. He took a particular interest in science and in 1926 was president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science when his alma mater, Oxford University, hosted the society’s annual general meeting.

He also visited the poverty-stricken areas of the country, and undertook 16 tours to various parts of the Empire between 1919 and 1935. On a tour of Canada in 1919, he acquired the Bedingfield ranch, near Pekisko, Alberta, and in 1924, he donated the Prince of Wales Trophy to the National Hockey League. From January to April 1931, he and his brother, Prince George, travelled 18,000 miles on a tour of South America, voyaging out on the ocean liner Oropesa, and returning via Paris and an Imperial Airways flight from Paris–Le Bourget Airport that landed specially in Windsor Great Park.

Though widely travelled, Edward was racially prejudiced against foreigners and many of the Empire’s subjects, believing that whites were inherently superior. In 1920, on a visit to Australia, he wrote of Indigenous Australians: “they are the most revolting form of living creatures I’ve ever seen!! They are the lowest known form of human beings & are the nearest thing to monkeys.”

In 1919 the Prince agreed to be President of the organizing committee for the proposed British Empire Exhibition at Wembley Park, north-west London. The Prince wished the Exhibition to include “a great national sports ground”, and so played a part in the creation of Wembley Stadium.

In 1917, during the First World War, he began a love affair with Parisian courtesanMarguerite Alibert (later Fahmy), who kept a collection of his indiscreet letters after he broke off the affair in 1918 to begin one with an English married woman, Freda Dudley Ward, a textile heiress.

Edward’s womanizing and reckless behavior during the 1920s and 1930s worried Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, King George V, and those close to the prince. Alan Lascelles, the prince’s private secretary for eight years during this period, believed that “for some hereditary or physiological reason his normal mental development stopped dead when he reached adolescence”. George V was disappointed by his son’s failure to settle down in life, disgusted by his affairs with married women, and was reluctant to see him inherit the Crown. “After I am dead,” George said, “the boy will ruin himself in twelve months.”

Second-in-line to the throne was the prince’s younger brother Albert (“Bertie”). Albert and his wife, Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother), had two children, including Princess Elizabeth (“Lilibet”), the future Queen Elizabeth II. George V favored Albert and his granddaughter Elizabeth and told a courtier, “I pray to God that my eldest son will never marry and have children, and that nothing will come between Bertie and Lilibet and the throne.” In 1929, Time magazine reported that the Prince of Wales teased his sister-in-law, by calling her “Queen Elizabeth”. The magazine asked if “she did not sometimes wonder how much truth there is in the story that he once said he would renounce his rights upon the death of George V – which would make her nickname come true”.

King Edward VIII and Mrs. Wallis Simpson on holiday in Yugoslavia, August 1936.

In 1930, George V gave the prince the lease of Fort Belvedere in Windsor Great Park. There, he continued his relationships with a series of married women, including Freda Dudley Ward and Lady Furness, the American wife of a British peer, who introduced the prince to her friend and fellow American Wallis Simpson. Simpson had divorced her first husband, U.S. naval officer Win Spencer, in 1927. Her second husband, Ernest Simpson, was a British-American businessman. Wallis Simpson and the Prince of Wales, it is generally accepted, became lovers, while Lady Furness travelled abroad, although the prince adamantly insisted to his father that he was not having an affair with her and that it was not appropriate to describe her as his mistress. Edward’s relationship with Simpson, however, further weakened his poor relationship with his father. Although King George V and Queen Mary met Simpson at Buckingham Palace in 1935, they later refused to receive her.

Edward’s affair with an American divorcée led to such grave concern that the couple were followed by members of the Metropolitan Police Special Branch, who examined in secret the nature of their relationship. An undated report detailed a visit by the couple to an antique shop, where the proprietor later noted “that the lady seemed to have POW [Prince of Wales] completely under her thumb.” The prospect of having an American divorcée with a questionable past having such sway over the heir apparent led to anxiety among government and establishment figures.

Edward VIII surrounded by heralds of the College of Arms prior to his only State Opening of Parliament in the House of Lords, November 3, 1936.

King George V died on January 20, 1936, and Edward ascended the throne as King Edward VIII. The next day, accompanied by Simpson, he broke with custom by watching the proclamation of his own accession from a window of St James’s Palace. He became the first monarch of the British Empire to fly in an aircraft when he flew from Sandringham to London for his Accession Council.

Edward caused unease in government circles with actions that were interpreted as interference in political matters. His comment during a tour of depressed villages in South Wales that “something must be done” for the unemployed coal miners was seen as an attempt to guide government policy, though it has never been clear what sort of remedy he had in mind. Government ministers were reluctant to send confidential documents and state papers to Fort Belvedere, because it was clear that Edward was paying little attention to them, and it was feared that Simpson and other house guests might read them, improperly or inadvertently disclosing information that could be detrimental to the national interest.

Edward’s unorthodox approach to his role also extended to the coinage that bore his image. He broke with the tradition that the profile portrait of each successive monarch faced in the direction opposite to that of his or her predecessor. Edward insisted that he face left (as his father had done), to show the parting in his hair. Only a handful of test coins were struck before the abdication, and all are very rare. When George VI succeeded to the throne he also faced left to maintain the tradition by suggesting that, had any further coins been minted featuring Edward’s portrait, they would have shown him facing right.

On July 16, 1936, an Irish fraudster called Jerome Bannigan, alias George Andrew McMahon, produced a loaded revolver as Edward rode on horseback at Constitution Hill, near Buckingham Palace. Police spotted the gun and pounced on him; he was quickly arrested. At Bannigan’s trial, he alleged that “a foreign power” had approached him to kill Edward, that he had informed MI5 of the plan, and that he was merely seeing the plan through to help MI5 catch the real culprits. The court rejected the claims and sent him to jail for a year for “intent to alarm”. It is now thought that Bannigan had indeed been in contact with MI5, but the veracity of the remainder of his claims remains open.

In August and September, Edward and Simpson cruised the Eastern Mediterranean on the steam yacht Nahlin. By October it was becoming clear that the new king planned to marry Simpson, especially when divorce proceedings between the Simpsos were brought at Ipswich Assizes. Preparations for all contingencies were made, including the prospect of the coronation of King Edward and Queen Wallis. Because of the religious implications of any marriage, plans were made to hold a secular coronation ceremony, not in the traditional religious location of Westminster Abbey, but in the Banqueting House in Whitehall.

Although gossip about his affair was widespread in the United States, the British media kept voluntarily silent, and the public knew nothing until early December.

On November 16, 1936, Edward invited British Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin to Buckingham Palace and expressed his desire to marry Wallis Simpson when she became free to remarry. Baldwin informed him that his subjects would deem the marriage morally unacceptable, largely because remarriage after divorce was opposed by the Church of England, and the people would not tolerate Simpson as queen. As king, Edward was the titular head of the Church of England, and the clergy expected him to support the Church’s teachings.

Edward proposed an alternative solution of a morganatic marriage, in which he would remain king but Simpson would not become queen. She would enjoy some lesser title instead, and any children they might have would not inherit the throne. This too was rejected by the British Cabinet as well as other Dominion governments, whose views were sought pursuant to the Statute of Westminster 1931, which provided in part that “any alteration in the law touching the Succession to the Throne or the Royal Style and Titles shall hereafter require the assent as well of the Parliaments of all the Dominions as of the Parliament of the United Kingdom.” The Prime Ministers of Australia (Joseph Lyons), Canada (Mackenzie King) and South Africa (J. B. M. Hertzog) made clear their opposition to the king marrying a divorcée; their Irish counterpart (Éamon de Valera) expressed indifference and detachment, while the Prime Minister of New Zealand (Michael Joseph Savage), having never heard of Simpson before, vacillated in disbelief. Faced with this opposition, Edward at first responded that there were “not many people in Australia” and their opinion did not matter.

Edward informed Baldwin that he would abdicate if he could not marry Simpson. Baldwin then presented Edward with three choices: give up the idea of marriage; marry against his ministers’ wishes; or abdicate. It was clear that Edward was not prepared to give up Simpson, and he knew that if he married against the advice of his ministers, he would cause the government to resign, prompting a constitutional crisis. He chose to abdicate.

Edward duly signed the instruments of abdication at Fort Belvedere on December 10, 1936 in the presence of his younger brothers: Prince Albert, Duke of York, next in line for the throne; Prince Henry, Duke of Gloucester; and Prince George, Duke of Kent. The next day, the last act of his reign was the royal assent to His Majesty’s Declaration of Abdication Act 1936. As required by the Statute of Westminster, all the Dominions consented to the abdication.

On the night of December 11, Edward, now reverted to the title and style of a prince, explained his decision to abdicate in a worldwide BBC radio broadcast from Windsor Castle. He was introduced by Sir John Reith as “His Royal Highness Prince Edward”. The official address had been polished by Winston Churchill and was moderate in tone. He famously said, “I have found it impossible to carry the heavy burden of responsibility and to discharge my duties as king as I would wish to do without the help and support of the woman I love.” Edward’s reign had lasted 327 days, the shortest of any British monarch since the disputed reign of Lady Jane Grey over 380 years earlier.

Edward departed Britain for Austria the following day; he was unable to join Simpson until her divorce became absolute, several months later. His brother, Prince Albert, Duke of York, succeeded to the throne as George VI. George VI’s elder daughter, Princess Elizabeth, became heiress presumptive.

Under changes introduced in 1931 by the Statute of Westminster, a single Crown for the entire empire had been replaced by multiple crowns, one for each Dominion, worn by a single monarch in an organization then known as the British Commonwealth. Though the British government, hoping for expediency and to avoid embarrassment, wished the Dominions to accept the actions of the home government, the Dominions held that Edward’s abdication required the consent of each Commonwealth state. This was duly given; by the Parliament of Australia, which was at the time in session, and by the governments of the other Dominions, whose parliaments were in recess. The government of the Irish Free State, taking the opportunity presented by the crisis and in a major step towards its eventual transition to a republic, passed an amendment to its constitution on December 11 to remove references to the Crown. The King’s abdication was recognized a day later in the External Relations Act of the Irish Free State and legislation eventually passed in South Africa declared that the abdication took effect there on December 10. As Edward VIII had not been crowned, his planned coronation date became that of George VI instead.

On December 12, at the accession meeting of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom, George VI announced he was to make his brother the “Duke of Windsor” with the style of Royal Highness. He wanted this to be the first act of his reign, although the formal documents were not signed until March 8 the following year. During the interim, Edward was universally known as the Duke of Windsor. George VI’s decision to create Edward a royal duke ensured that he could neither stand for election to the House of Commons nor speak on political subjects in the House of Lords.

Letters Patent dated May 27, 1937, re-conferred the “title, style, or attribute of Royal Highness” upon the Duke of Windsor, but specifically stated that “his wife and descendants, if any, shall not hold said title or attribute”. Some British ministers advised that the reconfirmation was unnecessary since Edward had retained the style automatically, and further that Simpson would automatically obtain the rank of wife of a prince with the style Her Royal Highness; others maintained that he had lost all royal rank and should no longer carry any royal title or style as an abdicated king, and be referred to simply as “Mr Edward Windsor”.

The Duke of Windsor married Simpson, who had changed her name by deed poll to Wallis Warfield, in a private ceremony on June 3, 1937, at Château de Candé, near Tours, France. When the Church of England refused to sanction the union, a County Durham clergyman, the Reverend Robert Anderson Jardine (Vicar of St Paul’s, Darlington), offered to perform the ceremony, and the Duke accepted. The new king, George VI, forbade members of the royal family to attend, to the lasting resentment of the Duke and Duchess of Windsor. Edward had particularly wanted his brothers the Dukes of Gloucester and Kent and his second cousin Louis Mountbatten to attend the ceremony.

Postcard mailed to Germany on June 30, 1937, bearing British stamps of the three recent kings.

The denial of the style Royal Highness to the Duchess of Windsor caused further conflict, as did the financial settlement. The Government declined to include the Duke or Duchess on the Civil List, and the Duke’s allowance was paid personally by George VI. The Duke compromised his position with his brother by concealing the extent of his financial worth when they informally agreed on the amount of the allowance. Edward’s wealth had accumulated from the revenues of the Duchy of Cornwall paid to him as Prince of Wales and ordinarily at the disposal of an incoming king. George VI also paid Edward for Sandringham House and Balmoral Castle, which were Edward’s personal property, inherited from his father, George V, and thus did not automatically pass to George VI on his accession. In the early days of George VI’s reign the Duke telephoned daily, importuning for money and urging that the Duchess be granted the style of Royal Highness, until the harassed king ordered that the calls not be put through.

Relations between the Duke of Windsor and the rest of the royal family were strained for decades. The Duke had assumed that he would settle in Britain after a year or two of exile in France. King George VI (with the support of Queen Mary and his wife Queen Elizabeth) threatened to cut off Edward’s allowance if he returned to Britain without an invitation. Edward became embittered against his mother, Queen Mary, writing to her in 1939: “[your last letter] destroy[ed] the last vestige of feeling I had left for you … [and has] made further normal correspondence between us impossible.”

Edward reviewing a squad of SS — Ordensburg Crössinsee — in Pommern on October 13, 1937.

In October 1937, the Duke and Duchess visited Germany, against the advice of the British government, and met Adolf Hitler at his Berghof retreat in Bavaria. The visit was much publicized by the German media. During the visit the Duke gave full Nazi salutes. The former Austrian ambassador, Count Albert von Mensdorff-Pouilly-Dietrichstein, who was also a second cousin once removed and friend of George V, believed that Edward favored German fascism as a bulwark against communism, and even that he initially favored an alliance with Germany. According to the Duke of Windsor, the experience of “the unending scenes of horror” during the First World War led him to support appeasement. Hitler considered Edward to be friendly towards Nazi Germany and thought that Anglo-German relations could have been improved through Edward if it were not for the abdication. Albert Speer quoted Hitler directly: “I am certain through him permanent friendly relations could have been achieved. If he had stayed, everything would have been different. His abdication was a severe loss for us.”

The Duke and Duchess settled in France. In May 1939, the Duke was commissioned by NBC to give a radio broadcast (his first since abdicating) during a visit to the battlefields of Verdun. In it he appealed for peace, saying “I am deeply conscious of the presence of the great company of the dead, and I am convinced that could they make their voices heard they would be with me in what I am about to say. I speak simply as a soldier of the Last War whose most earnest prayer it is that such cruel and destructive madness shall never again overtake mankind. There is no land whose people want war.” The broadcast was heard across the world and by millions in America. It was widely seen as supporting appeasement, and the BBC refused to broadcast it. It was broadcast outside the United States on shortwave radio and was reported in full by British broadsheet newspapers.

On the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939, they were brought back to Britain by Louis Mountbatten on board HMS Kelly, and the Duke, although an honorary field marshal, was made a major-general attached to the British Military Mission in France. In February 1940, the German ambassador in The Hague, Count Julius von Zech-Burkersroda, claimed that the Duke had leaked the Allied war plans for the defense of Belgium, which the Duke later denied. When Germany invaded the north of France in May 1940, the Windsors fled south, first to Biarritz, then in June to Spain. In July, the pair moved to Lisbon, where they lived at first in the home of Ricardo de Espírito Santo, a Portuguese banker with both British and German contacts. Under the code name Operation Willi, Nazi agents, principally Walter Schellenberg, plotted unsuccessfully to persuade the Duke to leave Portugal and return to Spain, kidnapping him if necessary. Lord Caldecote wrote a warning to Winston Churchill: “[the Duke] is well-known to be pro-Nazi and he may become a centre of intrigue.” Churchill threatened the Duke with a court-martial if he did not return to British soil.

In July 1940, Edward was appointed Governor of the Bahamas. The Duke and Duchess left Lisbon on August 1 aboard the American Export Lines steamship Excalibur, which was specially diverted from its usual direct course to New York City so that they could be dropped off at Bermuda on the 9th. They left Bermuda for Nassau on the Canadian steamship Lady Somers on August 15, arriving two days later. The Duke did not enjoy being governor and referred to the islands as “a third-class British colony”. The British Foreign Office strenuously objected when the Duke and Duchess planned to cruise aboard a yacht belonging to a Swedish magnate, Axel Wenner-Gren, whom British and American intelligence wrongly believed to be a close friend of Luftwaffe commander Hermann Göring.

The Duke was praised for his efforts to combat poverty on the islands, although he was as contemptuous of the Bahamians as he was of most non-white peoples of the Empire. He said of Étienne Dupuch, the editor of the Nassau Daily Tribune: “It must be remembered that Dupuch is more than half Negro, and due to the peculiar mentality of this Race, they seem unable to rise to prominence without losing their equilibrium.” He was praised, even by Dupuch, for his resolution of civil unrest over low wages in Nassau in 1942, even though he blamed the trouble on “mischief makers – communists” and “men of Central European Jewish descent, who had secured jobs as a pretext for obtaining a deferment of draft”. He resigned from the post on March 16, 1945.

Many historians have suggested that Hitler was prepared to reinstate Edward as king in the hope of establishing a fascist Britain. It is widely believed that the Duke and Duchess sympathized with fascism before and during the Second World War, and were moved to the Bahamas to minimize their opportunities to act on those feelings. In 1940 he said: “In the past 10 years Germany has totally reorganized the order of its society … Countries which were unwilling to accept such a reorganization of society and its concomitant sacrifices should direct their policies accordingly.”

During the occupation of France, the Duke asked the German forces to place guards at his Paris and Riviera homes; they did so. In December 1940, the Duke gave Fulton Ourslerof Liberty magazine an interview at Government House in Nassau. The interview was published on March 22, 1941, and in it the Duke was reported to have said that “Hitler was the right and logical leader of the German people” and that the time was coming for President Franklin D. Roosevelt to mediate a peace settlement. Oursler conveyed the content of the interview to the President in a private meeting at the White House on December 23, 1940. The Duke protested that he had been misquoted and misinterpreted.

The Allies became sufficiently disturbed by German plots revolving around the Duke that President Roosevelt ordered covert surveillance of the Duke and Duchess when they visited Palm Beach, Florida, in April 1941. Duke Carl Alexander of Württemberg (then a monk in an American monastery) had told the Federal Bureau of Investigation that the Duchess had slept with the German ambassador in London, Joachim von Ribbentrop, in 1936, had remained in constant contact with him, and had continued to leak secrets.

Author Charles Higham claimed that Anthony Blunt, an MI5 agent and Soviet spy, acting on orders from the British royal family, made a successful secret trip to Schloss Friedrichshof in Germany towards the end of the war to retrieve sensitive letters between the Duke of Windsor and Adolf Hitler and other leading Nazis. What is certain is that George VI sent the Royal Librarian, Owen Morshead, accompanied by Blunt, then working part-time in the Royal Library as well as for British intelligence, to Friedrichshof in March 1945 to secure papers relating to the German Empress Victoria, the eldest child of Queen Victoria. Looters had stolen part of the castle’s archive, including surviving letters between daughter and mother, as well as other valuables, some of which were recovered in Chicago after the war. The papers rescued by Morshead and Blunt, and those returned by the American authorities from Chicago, were deposited in the Royal Archives.

Photograph of the Duke of Windsor outside the White House on the date of the announcement of the Japanese surrender ending World War II, August 14, 1945.

After the war, the Duke admitted in his memoirs that he admired the Germans, but he denied being pro-Nazi. Of Hitler he wrote: “[the] Führer struck me as a somewhat ridiculous figure, with his theatrical posturings and his bombastic pretensions.” In the 1950s, journalist Frank Giles heard the Duke blame British Foreign Secretary Anthony Edenfor helping to “precipitate the war through his treatment of Mussolini … that’s what [Eden] did, he helped to bring on the war … and of course Roosevelt and the Jews”. During the 1960s the Duke said privately to a friend, Patrick Balfour, 3rd Baron Kinross, “I never thought Hitler was such a bad chap.”

At the end of the war, the couple returned to France and spent the remainder of their lives essentially in retirement as the Duke never occupied another official role after his wartime governorship of the Bahamas. Correspondence between the Duke and Kenneth de Courcy, dated between 1946 and 1949, emerged in a US library in 2009. The letters suggest a plot where the Duke would return to England and place himself in a position for a possible regency. The health of George VI was failing and de Courcy was concerned about the influence of the Mountbatten family over the young Princess Elizabeth. De Courcy suggested that the Duke buy a working agricultural estate within an easy drive of London in order to gain favor with the British public and make himself available should the King become incapacitated. The Duke however hesitated and the King recovered from his surgery.

The Duke’s allowance was supplemented by government favors and illegal currency trading. The City of Paris provided the Duke with a house at 4 Route du Champ d’Entraînement, on the Neuilly-sur-Seine side of the Bois de Boulogne, for a nominal rent. The French government exempted him from paying income tax, and the couple were able to buy goods duty-free through the British embassy and the military commissary. In 1951, the Duke produced a ghost-written memoir, A King’s Story, in which he expressed disagreement with liberal politics. The royalties from the book added to their income. Nine years later, he penned a relatively unknown book, A Family Album, chiefly about the fashion and habits of the royal family throughout his life, from the time of Queen Victoria to that of his grandfather and father, and his own tastes.

The Duke and Duchess effectively took on the role of celebrities and were regarded as part of café society in the 1950s and 1960s. They hosted parties and shuttled between Paris and New York; Gore Vidal, who met the Windsors socially, reported on the vacuity of the Duke’s conversation. The couple doted on the pug dogs they kept.

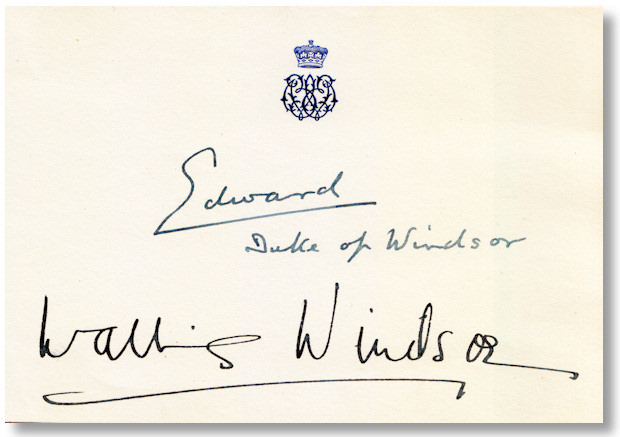

Post-abdication calling card signed by the Duke and Duchess of Windsor

In June 1953, instead of attending the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in London, the Duke and Duchess watched the ceremony on television in Paris. The Duke said that it was contrary to precedent for a Sovereign or former Sovereign to attend any coronation of another. The Duke was paid to write articles on the ceremony for the Sunday Express and Woman’s Home Companion, as well as a short book, The Crown and the People, 1902–1953.

In 1955, they visited President Dwight D. Eisenhower at the White House. The couple appeared on Edward R. Murrow’s television interview show Person to Person in 1956, and a 50-minute BBC television interview in 1970. That year, they were invited as guests of honor to a dinner at the White House by President Richard Nixon.

The royal family never fully accepted the Duchess. Queen Mary refused to receive her formally. However, Edward sometimes met his mother and brother George VI, and attended George’s funeral in 1952. Queen Mary remained angry with Edward and indignant over his marriage to Wallis: “To give up all this for that”, she said. In 1965, the Duke and Duchess returned to London. They were visited by Elizabeth II, his sister-in-law Princess Marina, Duchess of Kent, and his sister Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood. A week later, the Princess Royal died, and they attended her memorial service. In 1967, they joined the royal family for the centenary of Queen Mary’s birth. The last royal ceremony the Duke attended was the funeral of Princess Marina in 1968. He declined an invitation from Elizabeth II to attend the investiture of the Prince of Wales in 1969, replying that Prince Charles would not want his “aged great-uncle” there.

In the 1960s, the Duke’s health deteriorated. In December 1964, he was operated on by Michael E. DeBakey in Houston for an aneurysm of the abdominal aorta, and in February 1965 a detached retina in his left eye was treated by Sir Stewart Duke-Elder. In late 1971, the Duke, who was a smoker from an early age, was diagnosed with throat cancer and underwent cobalt therapy. On May 18, 1972, Queen Elizabeth II visited the Windsors while on a state visit to France; she spoke with the Duke for fifteen minutes but only the Duchess appeared with the royal party for a photocall as the Duke was too ill.

On May 28, 1972, ten days after the Queen’s visit, the Duke died at his home in Paris, less than a month before his 78th birthday. His body was returned to Britain, lying in state at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle. The funeral service was held in the chapel on June 5 in the presence of the Queen, the royal family and the Duchess of Windsor, who stayed at Buckingham Palace during her visit. He was buried in the Royal Burial Ground behind the Royal Mausoleum of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert at Frogmore. Until a 1965 agreement with Queen Elizabeth II, the Duke and Duchess had planned for a burial in a cemetery plot they had purchased at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, where the Duchess’s father was interred. Frail, and suffering increasingly from dementia, the Duchess died 14 years later, and was buried alongside her husband.

In the view of historians, such as Philip Williamson writing in 2007, the popular perception in the 21st century that the abdication was driven by politics rather than religious morality is false and arises because divorce has become much more common and socially acceptable. To contemporary sensibilities, the religious restrictions that prevented Edward from continuing as king while planning to marry Simpson “seem, wrongly, to provide insufficient explanation” for his abdication.

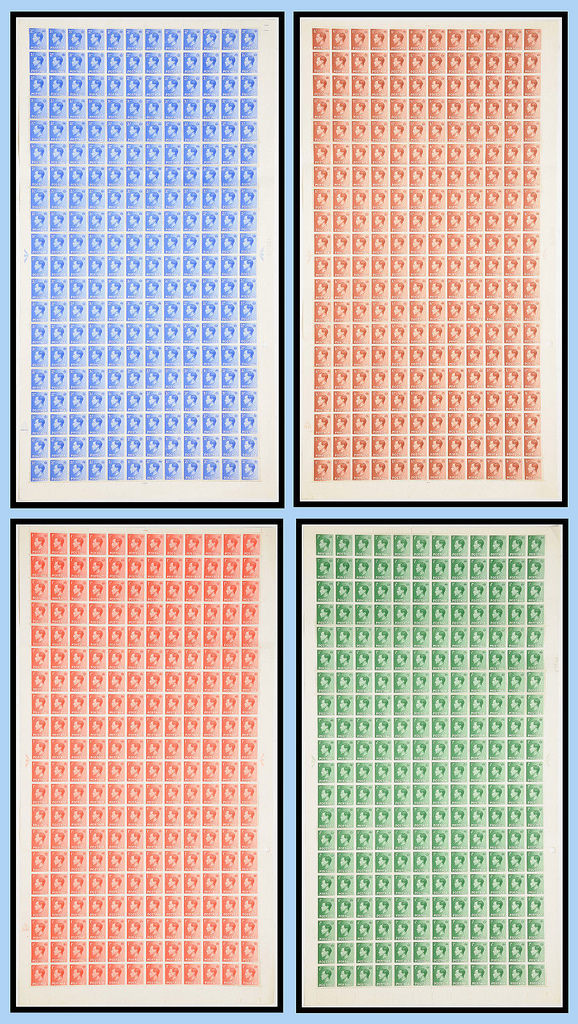

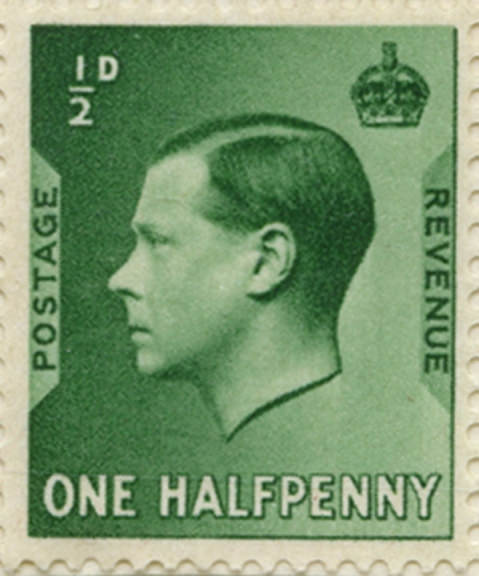

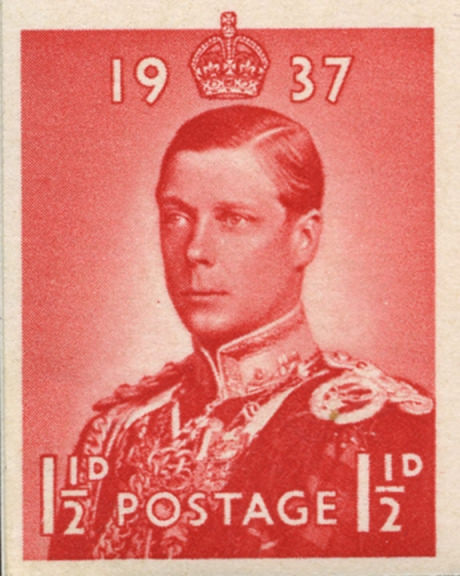

Planning for the release of definitive and commemorative stamps bearing King Edward VIII’s portrait began soon after the start of his reign in January 1936. Only one definitive set would see release in the short period before his abdication, that by Great Britain. Stamps by other members of the British Commonwealth barely got past the design stage, although a few proofs eventually made it into collectors’ hands.

Portrait of Edward VIII by Hugh Cecil, 1936.

Essay approved by Edward VIII, March 1936.

For the Great Britain definitives, the profile portrait chosen was taken by Hugh Cecil’s studio. The design was suggested by H.J. Brown, an 18-year-old man, sent in February 1936 to the postal authorities. It inspired Harrison and Sons printers. The only graphic decorations on the stamp were the crown, the denomination in the upper corners, and the word POSTAGE at the bottom. Brown’s project, the simplest of all submissions, placed the words POSTAGE and REVENUE on the lateral sides. The Post Office wrote to Mr. Brown telling him that his proposed design could not be used. After the stamp came out, clearly using Brown’s design, Brown’s father issued a statement regretting the Post Office’s deceit.

Watermarked with a crown and E8R, the stamps were issued on September 1, 1936, for the halfpenny green, the three half- pence red-brown and the two pence half-penny bright ultramarine (called bright blue in the Stanley Gibbons catalogue) and on September 14 for the one penny crimson (scarlet per Stanley Gibbons). At the time, the stamps were considered a curiosity. They were the first to feature a photograph, not an etching, a design choice apparently made by the king himself who also bucked tradition by selecting a left-facing portrait despite convention dictating he should look to the right. About 30 million of the new stamps were sold on the first day of their release with queues at all-night post offices awaiting the midnight release. Edward VIII stamps were still being dispensed from stamp machines until the very beginning of 1938. As the standard postage stamps of the period, they were sold in large numbers. After the abdication many people hoarded them, believing that they would become valuable. As a result, a larger percentage of these stamps probably survived than those of his father’s or brother’s stamps.

Great Britain – Scott #232b booklet pane of four with two advertising labels.

E8R watermark on Great Britain Edward VIII booklet pane

The four stamps are numbered as Scott #230-233 or Stanley Gibbons #457-460 and were printed by photogravure in sheets of 240 (12 across by 20 down), perforated 15×14. In addition, the three lower denominations appeares in booklet panes of six while the 1½-penny stamps also came in a booklet pane of four with two printed labels (released in October 1936) or a booklet pane of two. All of these have been assigned minor numbers by Scott (#230a, #231a, and #232a-c). The Scott catalogue also mentions that inverted watermarks on the three lowest values are usually from the booklet panes. Additionally, Stanley Gibbons lists a double impression of the 1-penny green (SG #457a) in their Commonwealth & British Empire Stamps 1840-1952 catalogue and mentions that there is further detailed information on the Edward VIII stamps to be found in Volume 2 of the Stanley Gibbons Great Britain Specialised Catalogue (which I don’t have a copy of). I do own used copies of the four stamps in this set, choosing to use Scott #231 based solely on its December 1936 postmark (which could be dated the 2nd, the 12th or the 22nd). Research for this article has caused me to want to obtain additional copies of the stamps, unused and on cover.

Essays prepared in 1936 by Harrison & Sons Ltd. for the unissued Edward VIII Coronation stamp set planned for May 1937.

Essays were also made for the British Post Office by Harrison & Sons to mark the planned May 12, 1937, Coronation of Edward VIII. These portrayed the King wearing different military uniforms, such as the Bertram Park’s pictures of Edward VIII wearing Seaforth Highlander and Welsh Guard uniforms. In March 1936, the King accepted the idea of larger stamps picturing his effigy and castles. The abdication ceased all designing efforts despite essays been made.

The four British definitives were overprinted to be used in the British post offices in Morocco. For Tangier, the name of the town was overprinted alone. MOROCCO / AGENCIES was overprinted with a new face value in French centimes or Spanish céntimos depending the zone of the post office.

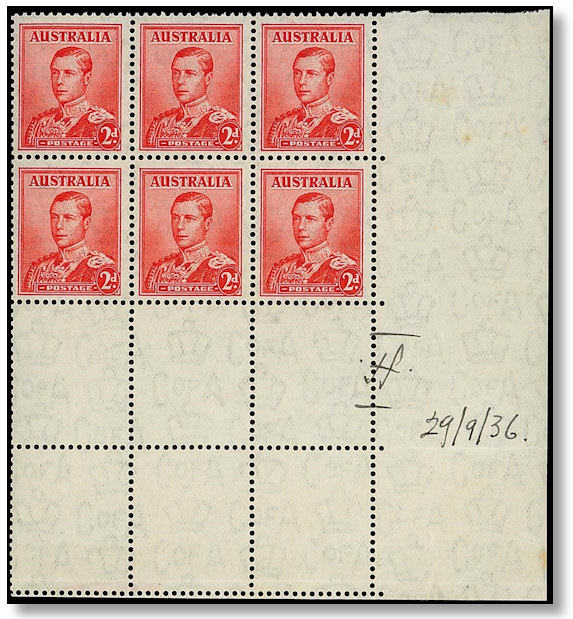

Unissued 2-pence red Edward VIII printed by Australia in October 1936. Only six copies exist today.

A 2-pence red stamp was prepared for release by Australia using a photograph of the king in uniform. The sole ornaments were the denomination into an oval in the bottom right corner and the red POSTAGE bar at the bottom. Printing of this stamp began in September 1936 at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia’s printing branch. All operations were stopped with the abdication.

Despite the destruction of the stock and all material needed for the printing, signed corner block of six of the Australian 2-pence red stamps was in the hands of a British collector until recently. On September 29, 1936, William Vanneck, 5th Baron Huntingfield, Governor of Victoria, had visited the plant and was invited to sign and date one of the finished sheets. In the name of the Commonwealth Bank, printer John Ash offered the sheet to the Governor in October. When news of the abdication reached the printers, it was decided to destroy the printing plates, ink and stamps that had already been printed which amounted to 71 million 2-pence stamps as well as those in denominations of one penny, 3 pence and 1 farthing to be burned.

John Ash wrote to the Baron Huntingfield’s private secretary on December 16, 1936:”

“Our instructions are that everything connected with the issue contemplated is to be completely destroyed, and all is in readiness for the Auditor-General with the exception of the sheet of stamps which His Excellently kindly consented to accept in anticipate of the official issue of the series.

“We have been in communication with the postal authorities and the Chairman of the Bank in this matter, and we find ourselves in the position that we are reluctantly compelled to ask that His Excellency will arrange at his convenience to have the sheet returned to us.“

A note bearing the governor’s initials, returned by the next day’s post, replied: “Sheet sent back less 6 stamps … which I mentioned over the telephone.” Ash replied that afternoon, asking if Huntingfield could also return the block of six stamps snipped from the bottom left-hand corner of the sheet.

The governor demurred. “Informed Ash that stamps had been sent to England. Thought it very doubtful if I could obtain possession.” The stamps had been sent to Sir William Vestey, the first Baron Vestey, who had a new enthusiasm for stamp collecting, having joined the Royal Philatelic Society some months before.

Ash, unable to press the governor further, relented, and the six stamps escaped the burning and disappeared into the private collection of the Vestey estate until October 2014, when Sir Samuel Vestey, a grandson of Sir William, included them in a lot for the London auction house Spink. Sir Samuel, the third Baron Vestey, is best known in Australia as the British landholder and cattle owner on the other side of the Gurindji walk-off in 1966.

The block of six, which had been snipped from the sheet using scissors, much to the horror of later philatelists, sold for £240,000. The original letters between Huntingfield and Ash were included in the sale. The anonymous buyer offered a nonmarginal single stamp for auction in 2015, which sold through Melbourne’s Phoenix Auctions for $172,912 in Australian dollars, described by the Scott Standard Postage Stamp Catalogue as then equivalent to US$123,600. It was the highest price paid to date for a single commonwealth of Australia stamp.

Lot #224 in a June 26, 2017, auction by Mossgreen of Melbourne was this copy of the unissued Australian 2-pence red Edward VIII stamp with margin selvage.

A second single mint stamp with two attached stamp-size pieces of perforated blank margin in a vertical strip was listed by the Melbourne house Mossgreen for auction on June 26, 2017, with an estimate of $120,000 Australian (roughly US$90,520). The piece was described as “hinged at the base of the margin only otherwise unmounted.” Lot #224, however, remained unsold. The full description from tbe Mossgreen auction catalogue follows:

“Lot 224 of 1416: 1936 Unissued 2d scarlet BW #174E(2) marginal example from the base of the sheet unusually with the comb perforations extended into the margin & thus presenting as two entirely void “stamps” at the base, hinged at the base of the margin only otherwise unmounted, Cat $120,000. One of the great rarities of the Australian Commonwealth and the British Empire and the pre-eminent stamp from the very brief reign of King Edward VIII. This is the lower-left unit from what was formerly Lord Vestey‘s corner block of 6. The corner block of 4 remains in the hands of the purchaser from the 2014 Vestey auction in London. The other — non-marginal — single was sold at a Melbourne auction in July 2015 for $172,912. Our estimate and reserve should therefore be seen as conservative.

“David, Prince of Wales ascended to the throne on the death of his father King George V on 20.1.1936 — not the 10th as stated in the ACSC — taking the name Edward VIII. Profligate by nature, an admirer of Mr Mussolini and Mr Hitler, and insistent on marrying the twice-divorced American Mrs Wallis Simpson, he was considered by the British Establishment to be an unfortunate “choice” for King. Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin and his cohorts — including the Archbishop of Canterbury who declared that the King, as Head of the Church of England, was barred from marrying a divorced woman — brought so much pressure to bear that Edward felt compelled to abdicate so he could marry the woman he loved. The abdication occurred on 10.12.1936, before his proposed Coronation, and 1936 became known as “The Year of the Three Kings”, Edward’s brother Albert, Duke of York, becoming king as George VI.

“In Australia, preparations for a new series of stamps featuring KEVIII commenced early in 1936. In April, an official portrait by Bertram Park was supplied to the Note Printing Branch. By December, printing of the base letter-rate 2d value was well advanced, while smaller quantities of the proposed 1d 3d & 1/4d had also been printed. However, the abdication caused the authorities in Australia to cancel plans for the issue and it was ordered that every example of the printed stamps, and every artefact associated with their production, was to be destroyed.

“Printing of the 2d scarlet had commenced on 29.9.1936, in the presence of the Governor of Victoria, Lord Huntingfield. As a memento of his visit, the Governor was presented with the first sheet to be printed. After the order was given to eradicate all evidence of the proposed issue, the Governor was requested to return the sheet. He dutifully complied but the lower-right corner block of 6 had been removed and gifted by the Governor to an unnamed aristocratic friend in England. (Not wishing to upset the British Establishment, in 1941 and with bigger things on their minds, the government decided not to pursue the matter further.) All essays, proofs and all other printed stamps, including some 71,000,000 of the 2d denomination were destroyed. Not a single example was retained for the Post Office records. Nor was an example presented to the Royal Collection. It is therefore certain that only the Vestey block of six survived.

“The stamp offered here is accompanied by an erudite article by Richard Breckon published in Gibbons Stamp Monthly of October 2014, a reproduction of seven photographic essays improperly retained by the printer John Ash, and colour photocopies of the correspondence between Ash and Lord Huntingfield including the latter’s hand-written notes ‘Sheet sent back less 6 stamps 17.12.36’ and ‘19.12.36 Informed Ash that stamps had been sent to England. Thought it very doubtful if I could obtain possession’.”

The remaining four stamps from the original block of six Australian stamps were reported by The Guardian in June 2017 to be placed in a public collection.

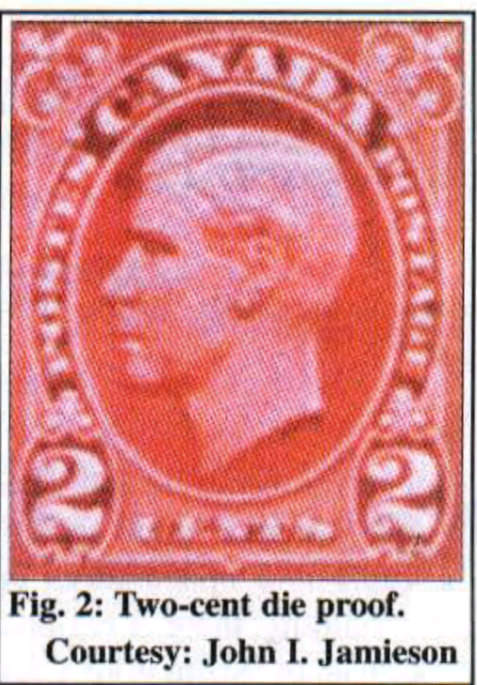

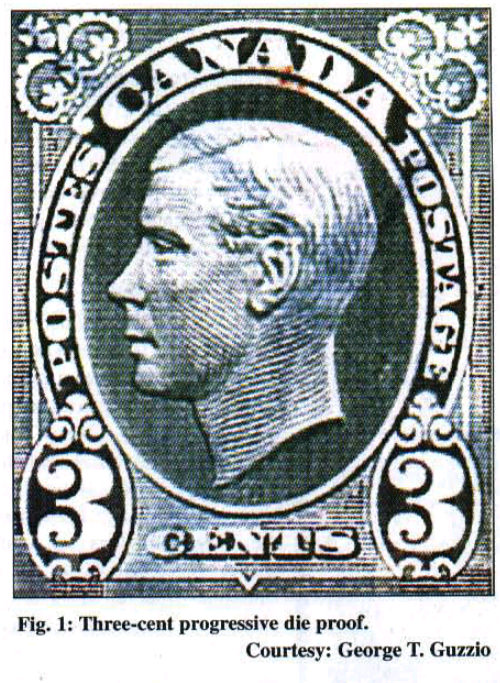

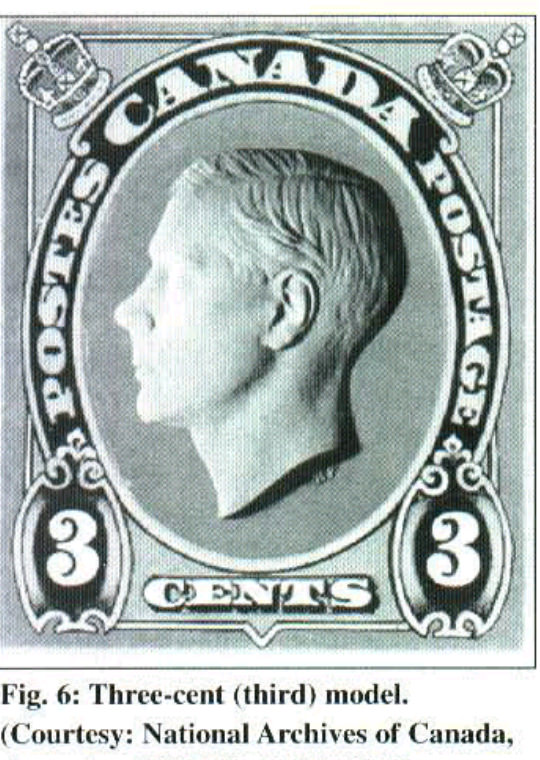

Essays and die proofs for unissued Edward VIII stamps prepared by Canada.

In March 1936, the Canadian Post Office received the photographic profile the new King wanted to be used and in June it obtained the one received by the Royal Mint. The Canadian Banknote Company worked on traditional ornamented designs with the two pictures with the help of the American Banknote Company, New York. In October, the Post Office received a plaster cast by British artist Hugh Paget. Finally, on December 1, 1936, the project was accepted by the Lord Tweedsmuir, Governor-in-Council. Two die-proofs were sent to London for the King to approve, but arrived after the abdication and were brought back to Canada.

The official destruction of Canada’s Edward VIII stamp dies and proofs took place on January 25 and 27, 1937; some essays were kept in the archives and the two plaster casts were saved by coin engraver Emmanuel Hahn and a postal officer. The prepared design was used with Bertram Park’s portrait of King George VI and released on April 1, 1937.

In the Falkland Islands, George Roberts redrew photographs of the archipelago’s fauna, human activities and coat of arms. These illustrations were inscribed inside a rectangular frame bearing two upper corner circles: the right side one for a crown and the left one for the profile of King Edward VIII, from the same picture as the definitives released by Great Britain.

After the abdication, the designs were reworked by Roberts. Edward VIII’s profile in a circle was replaced by a portrait of King George VI in an oval, with his military collar still visible. This stamps were issued on January 3, 1938.

Please note that with this article I have gone off of my pledge to only illustrate philatelic items from my own collection. The only item that I own pictured above is the used copy of Great Britain Scott #231 featured at the head. Most of the other items pictured were sourced from several excellent websites detailing the Edward VIII stamps, both those released and unissued. The Stanley Gibbons site is always worth a look and I found a lot of information about the booklet panes on another site specializing in these. Two sites provided a wealth of interesting information about the unreleased trials and proofs — The Postal Museum has several pages about the British stamps while an excellent article about the design process for Canada’s unreleased definitives that originally appeared in the March-April 1999 Canadian Philatelist can be found on the website of The Royal Philatelic Society of Canada.