I’ve already reviewed later volumes in this series, so I thought I’d go back to look at the first two.

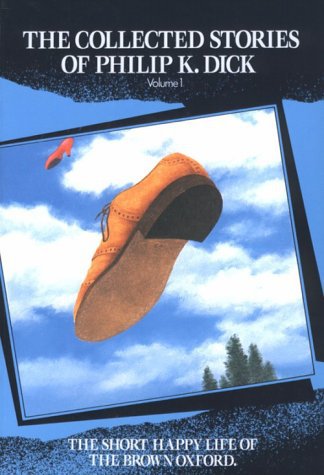

Raw Feed (1991): The Collected Stories of Philip K. Dick, Volume 1: The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford, 1987.

“Preface” — This is an interesting piece by Dick on what he valued in sf. Dick makes the valid point that all fiction involves dislocation from the reader’s world but that sf involves a major conceptual dislocation. Dick eloquently speaks of the joy in reading sf coming from the “chain reaction of ideas” set off in the mind while reading good sf. What is good sf to Dick? New ideas or new variations of old ideas. He quite clearly says it isn’t just the future or advanced technology. I disagree with this view. To me Dick is guilty of committing a variant on the sin of many other sf critic/author: he insists that sf meet some functional definition (define man’s relation to technology, the effect of change, prepare man for change, the dreams of technological society) and not assign a descriptive definition like it being fantasy with a pseudo-scientific or technological or scientific or pseudo-technological rationale. [I think younger self missed the importance of “good” in Dick’s argument. He may have considered a lot of things sf — just bad sf.] Many sf critics and authors seem quite content to denounce large parts of the sf genre as unfit for the label. I can’t see the need for this.

“Foreword“, Steven Owen Godersky — It occurs to me in reading the Philip K. Dick Society’s Newsletter (and biographies and interviews of Dick) that the quality and character of Dick scholars varies greatly: some examine his mystical visions and religious themes for signs of mental illness, philosophical speculation, or divine revelation; some proudly point to him as one of sf’s best, others — scornful of most sf — point to him as a wasted gem in the garbage of sf; some see him as liberal, others as paranoid. Godersky sees a major theme — which he obviously, in a liberal way, likes — of anti-military, anti-war. That may be true but I suspect this strain in Dick’s work has more to do with living in the tense 1950s and having a strong distrust in authority.) Dick may be one of those rare authors that many a critical theory and observation could apply to. Dick’s contradictory statements, the philosophical/religious speculations, his concern over the small, his characterization and empathy, his distrust of authority and descriptions of reality all mesh to create a multi-faceted and complex man and body of work that can be described in political terms (such as Cold War satires), religious terms (the gnosticism of later books), and philosophy (e.g. Paul Williams description of the I Ching‘s influence on Dick). In some sense, most of these views are right, provide insight, and can be supported (and almost all contradicted) by evidence. Godersky makes the valid observation that Dick’s fiction has cosmic struggles between good and evil, death and life, order and entropy, callousness versus empathy often taking place in out of the way corners in a muted, hidden way between rather small, ordinary figures. The everyday, the mundane in Dick can have cosmic significance.

“Introduction“, Roger Zelazny — Zelazny gives his personal reminisces about Dick. In his statements on what he likes about Dick, he mentions some of the things I like best about Dick: his humor, his mixing of the everyday with the strange and horrifying, his everyman characters who are often engaged in desperate, but unobvious, cosmic struggles.

“Stability” — This is a previously unpublished story with just cause. It is a mood piece (whose ending seems to owe much to the image of ranked rows of workers marching to tend their monstrous machine masters in the film Metropolis) that uneasily combines a fantasy feel (the evil city imprisoned and watched by a mysterious guardian in another time/dimension) with an sf feel. Dick, with his tale of time travel, introduces the elements of reality distortion and temporal dislocation which went on to become characteristic of his works.

“Roog” — This unpretentious little story has, at first glance, merely a charming notion to recommend it: a dog guarding his master against the aliens who look like garbage men to everyone else. But Dick’s notes to this story have a lot to say about Dick’s fiction and fiction in general. Dick stories are written in an unpretentious style, very naturalistic and not overblown but still conveying much emotion. Yet, because Dick does not write in a bloated, obviously symbol laden “literary” style the significance of the issues and themes is not always obvious. (I missed most until I read Dick’s notes.) As Dick points out, this story is about an obscure menace and the loyalty of a dog trying to warn his uncomprehending master and being bitterly frustrated. Besides the familiar Dick themes of love/friendship and loyalty, there is the quintessential Dick theme of reality’s nature and the differing perceptions of sentient minds. Dick based the story’s dog on his own dog who barked at garbage men on Friday mornings — convinced they were there to steal the master’s treasure. Dick placed himself into the mind of a crazy dog. Others speak of Dick’s empathy, his questioning of reality, his spiritual concerns, but for me these are all contained in one of the things I admire most in his writing: his characterization. As the Wall Street Journal blurb says, Dick put you in other people’s minds and all his emotion and philosophical speculation contribute towards that. Important themes, as he said, but, with a prose style lacking flashy metaphors and symbol-laden, wordy “literary” prose, we don’t see it at first and his powerful themes are not readily apparent.

“The Little Movement” — Like “Roog”, this is another Dick story with a cosmic struggle played out in a seemingly trivial venue and manner. Dick, always concerned with authority and the oppressed, gives us a child manipulated and ordered about by another authoritarian figure in his life: a literal tin soldier. I can’t say I liked this story better the second time around but I appreciated it more.

“Beyond Lies the Wub” — It was interesting to read Dick’s first published story. It shows some of Dick’s delightful, strange humor in the wub conversing with his would-be devourers. This story has quite obvious references (and resonances to use the lit-crit phrase) with the Eucharist. Captain Franco is possessed by the wub’s personality after he eats his flesh. The wub is with him always in spirit and, in some ways, flesh. The character of Captain Franco is an earthman devoted to talk of, the wub says, killing and cutting. The wub speaks to us and him in another Dick attempt to tell us of the brotherhood of sentience.

“The Gun” — This is one of those stories that chastises man for being such a suspicious, warlike animal (standard theme for ’50s sf). An (evidently) alien exploration crew finds a desolate planet, the victim of that rare event — interspecies war — which seems to be Earth. A treasure trove of cultural artifacts for this dead race is guarded by a huge gun that knocks out approaching spacecraft. The explorers manage to disable the gun and take back some rotting artifacts. (One of the crew remarks it would serve the race right for being so suspicious if no one rescued their cultural artifacts.) However, when the aliens leave the forces of thanatos (as always, symbolized by the mechanical in Dick’s works — here in a matter like his “Second Variety“) ensure man’s memory will not be saved and, Dick says, it serves us paranoid, hostiles right.

“The Skull” — This is a variant (which reminded me of The Terminator [as I’ve mentioned before, PKD had a lot more grounds to sue James Cameron for plagiarism than Harlan Ellison did) of that very common time travel theme of going back in time to kill someone. Here a society wants to strangle a religion of civil resistance and pacifism (war and reactions to it were an understandably large part of 1950’s sf) in the cradle by killing its founder before he can make his one speech that starts the movement. No one knows the man’s identity. I liked the moment when the would-be assassin realizes (as I’m sure most readers — as I did — realized already) he is the founder. Dick does a very nice job of showing the emotion of a man contemplating his future, dead skull. I liked the delicious joke (and playful variant of the story of Christ’s death and resurrection) of the assassin starting a religion by uttering joking, “death-bed” riddles. His seemingly moral statements are descriptions of the future (and his past life), desperate attempts by a dying man to be remembered through paradoxes: a religion of non-resistance and empathy is started by a violent man who despises it. I read an article in one of the PKDS’ newsletters talking about how the past becomes the future, the present the past in Dick’s work. I didn’t know — at the time — what the author was talking about but this is a perfect example.

“Mr. Spaceship” — This may be one of the first stories featuring the idea of a man/spaceship [cyborg spaceships go back to at least 1945 with Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore’s “Camouflage] cyborg. Dick’s philosophical point in this story is not new and I don’t agree with it: warfare is not instinctual, we can overcome it and can survive without doing it– even against aliens — anymore. Professor Thomas concedes (as he prepares to play God in spaceship form)to his Adam and Eve) he may be wrong. Dick’s characteristic point is you have to try to overcome evil even if your effort is futile and/or doomed.

“Piper in the Woods” — This is one of those 1950s a-day-in-the-life-of pieces of sf common to the period. Our protagonist is a military psychologist — not exactly the every day white collar worker of 1950s period sf but close enough. Dick makes little use of scientific realism here (or in any other story). People careen between the asteroids (fantastically like little pastoral worlds) like Packards down suburban streets. The story is filled with psychological concepts and jargon (usually Freudian) like a lot of fifties sf (though Dick and Alfred Bester probably made the heaviest use of ideas deriving from psychology). The best part of the story is the humorous dialogue between the men who have turned into vegetables via mental identification/empathy. This is something of a mild beatnik/dropout satire on goal-oriented fifties society — though the psychologist rightly points out little is possible without goals and struggle (including art) so it’s an ambivalent satire at best.

“The Infinites” — This is one of those typical mutant superman stories. Dick throws in the touch of having the radiation induce an evolutionary process which is not random but directed toward a goal. As usual, Dick’s sympathies are with the individual. Power-crazed (or, more accurately, paternalistic) Harrison Blake is seen as evil (though Dick often underplays his “evil” characters — they seem bland or relatively normal) in his desire to dominate his fellow Terrans. The other characters suffer emotionally from their mutation. I liked the twist (Dick’s stories — especially the short ones — often have a twist) of having mutated hamsters — who are superior to even the human mutations — help our heroes back to normalcy.

“The Preserving Machine” — This strange, charming, slightly disconcerting story is even better on the second read. There is a poignancy here about trying to preserve the beauties of civilization — here music — from destruction. Doc Labyrinth experiences the pain of a creator whose creations — imbued with independence, adaptability, and the will to survive of necessity — change to something not beautiful like the original. Doc despairs but keeps the hope that something will work. (Dick’s characters often carry on in the face of despair and defeat — they keep the faith in the value of the struggle for good though it may prove futile.) Perhaps the stately beethoven beetle at story’s end is a sign that Doc’s faith is justified.

“Expendable” — A fun (if absurd) and paranoid story about a man who discovers the truth about the ancient war between invader man and native Terran insect and man’s created ally, the spider. I liked the blackly funny twist at the end where the spiders apologize for making the man think he will be saved. They were just referring to his race.

“The Variable Man” — This is a very ’50s sf story: a tale of war, social engineering along mathematical lines, and satire. Dick gives us an Earth society locked in combat with an encircling, corrupt Centauran Empire. This story reminds me, in its mathematically determined society which has little concern for one individual life and its plot of Dick’s Solar Lottery. In this story, the expansion of man through the universe via the newly discovered ftl drive is celebrated. I liked what I took to be a satirical element in two societies waging war via competing weapon design programs, never actually shifting to production until they are sure they have a large enough edge. In this age of chaos science, it’s interesting to note that the incalculable effects the variable man’s presence yields is sort of a premonition of that. Of course, there are problems in the logic of this. If the Centaurans have the odds advantage. why don’t they attack? Could spies really know all the relevant information (chaos science says no, plot necessity says yes)? There is also Dick’s usual loose logic and science: ftl travel is the outcome of the story but the movement of Terran space forces makes it sound as if it’s already a reality. A certain casualness (to put it charitably) about science permeates Dick’s stories: microgravity of asteroids is never mentioned, asteroids have atmospheres, Mars almost always has life. This may be one of the most action oriented Dick stories (along with Solar Lottery) I’ve read. Dick’s description of the military conflict between Reinhart and Sheikov is competently done if not real exciting. Thomas Cole, the Variable Man, is a familiar Dick figure: the handyman (here also a symbol of earlier times when men intuitively knew machines and did not worship them the way Reinhart does his SRB machines) who is a hero and, ultimately, the technological (and, possibly, political) savior of man — or, at least, a decent man trying to do his best in the world.

“The Indefatigable Frog” — This was a good natured if lightweight, amusing story of two stubborn, sometimes mean-spirited, college professors dedicated to getting a conclusive answer to an old logic puzzle first proposed by the Greek Zeno (the puzzle deals with whether a frog at the bottom of a well can jump to the top if each jump is half as long as the preceding).

“The Crystal Crypt” — This is an action packed story of Terran sabotage against a Martian city. The twist ending of the Terran turning out to be a Martian agent was predictable. The only new idea here was taking an entire Martian city, by shrinking it, as hostage.

“The Short Happy Life of the Brown Oxford” — I enjoyed this whimsical, gently humorous story of Oxfords and high heel shoes coming to life. The Doc Labyrinth stories prove Dick did have a definite talent for what’s called “light fantasy”. (I’d argue it’s sf.). Is there a deeper philosophical significance here? Perhaps it’s Dick’s old concern for the relationship of the animate and inanimate. Dick, if you want to give this story a philosophical/religious significance, seems to taken an animistic stance: even inanimate objects have the potential for life if sufficiently irritated.

“The Builder” — This story, predictably, turns out to be a retelling of the Noah story. The emotion of the ark builder and his son is effectively portrayed, but it’s mainly notable for its attack on fifties’ society as bigoted, nosy, intrusive, and conformists.

“Paycheck” — I agree with Paul Williams (Dick’s one time agent, literary executor, biographer, and head of the Philip K. Dick Society) that this would make an interesting sequel to the movie Total Recall based on Dick’s short story “We Can Remember It for You Wholesale”. [It was turned into a forgettable movie of the same name in 2003.] This is a fast-moving, paranoid tale of a man, Jennings, who has been mysteriously employed for the past two years. The ruthless Security Police want to know what he’s been doing. The problem is he doesn’t know — the knowledge was removed from his brain as part of his employment contract. To further worsen matters, his pre-amnesiac self as elected to take a bagful of trinkets in lieu of money. But, in one of the most intriguing aspects of this story (and the genesis of the story according to Dick’s notes), those trinkets prove to be quite valuable as they unfailing help as he finds himself (in the story’s political aspect) caught between the Scylla and Charybdis of governmental and economic forces. In this future, it is not a conflict, as in medieaval times, between the Church and State but between State and Corporation with individuals (always Dick’s concern is with freedom and the individual) as hapless pawns. With the aid of time-viewing and “scoop” equipment, Jennings’ past, pre-amnesiac self takes on the aura of an omniscient, pre-determing god who unfailingly guides Jennings as he manages to blackmail his way into a revolutionary organization whose long-term goal is to overthrow the government and the corporations. I liked this story a lot.

“The Great C” — According to the notes for this story, it was partly used for Dick and Roger Zelazny’s collaboration Dies Irae in my favorite part of the novel: the encounter with the old, surly, senile computer. This story uses the plot of the primitive tribe (here survivors of an atomic war) sacrificing to a god to make a symbolic point. Here the god is a symbol of the mechanical, thanotos force of war. The Great C caused the war and now literally eats people to remain alive.

“Out in the Garden” — This short, rather horrifying tale is a modern retelling of the Zeus-Leda story. A man finds that son is the product of a liasion between his wife and Zeus in duck form.

“Colony” This is a delightfully paranoid story along the lines of John Carpenter’s The Thing (and its inspiration, John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?”) but with a heightened twist: here the mimicking life-forms impersonate inanimate objects. This story ends with the absurd, horrifying image of the men and women of the survey team heading naked into the mouth of an alien lifeform disguised as a spaceship. This story also features one of the funniest lines in all of the Dick’s works when Captain Taylor, talking about how his red-and-white rug attacked him, says, “I — I trusted it completely.”

“Prize Shop” — This story has little to recommend it. It seems to be Dick’s ode to Jonathan Swift’s (who, I understand, he admired) Gulliver’s Travels. The story does, in its talk of launch cradles and other scientific and technological jargon, provide (at least it provoked the thought in me but other sf works are better examples) an interesting example of sf rationalizing and extrapolation via nomenclature. The ending wasn’t predictable, but it wasn’t very interesting either, and I did suspect the involvement of time travel.

“Nanny” — This story, with its children and passages of pastoral description (the most, I think, in any Dick story I’ve read) reminded me a great deal of Ray Bradbury’s work though I don’t know how Dick felt about the latter. Bradbury would have had a warmer relationship between the children and Nanny, but the touch of arming the robot nannies and having them fight is an odd, unsettling, uniquely Dickian touch. The story seemed to be a bizarre, satirical twist on planned obsolescence. Here the obsolescence is vigorously enforced in Darwinian struggle between competing products — a struggle which results in increasingly better products. But these products increasingly taken on the sinister air of weapons and not loving nannies — there lies the story’s odd tension. But the story seems — perhaps unintentionally — to also be a commentary on men’s inherent fascination with observing and causing violence.

More reviews of fantastic fiction are indexed by title and author/editor.

Advertisements Share this: