I won’t lie, David and I’s working relationship was tumultuous at best, and downright caustic at its worst. For years after we completed what was my feature film directorial debut, “American Reel”, I thought he was the biggest jerk I had ever worked with. The fact that we even managed to complete principal photography for a movie that relied upon a man who was consistently a minimum of one hour late to set every single day of an 18 day shooting schedule was a minor miracle. How in the world do you become like this and still stay employed? I would wonder to myself as I decompressed for weeks after wrapping the film. But there was still something about him that I had grown to admire, and even thought of him as a friend. I know that it was reciprocated at some level, since only a few months after completing the film he invited me to his wedding with Marina Anderson.

By the time David and I had worked together on “American Reel” he had been making movies since before I was even born. So, the fact that he had a bit of attitude in dealing with a 24 year-old director was, in hindsight, somewhat understandable. I mean, this guy had literally seen it all, done it all, survived it all, and was old enough to be my grandfather. There was not much that I could do to impress him, and I knew that full well going into the deal. All that I hoped was that he would take me under his wing, teach me a few things, and make me look good for my first movie directing gig. Although I was never a huge David Carradine fan – I had never even watched “Kung Fu” – I had done enough homework on him to know that he was older and wiser and worthy of my study. What I didn’t count on was his on-set persona, which was a far cry from the “let’s do a Hollywood lunch and meet each other” persona. A very far cry, indeed.

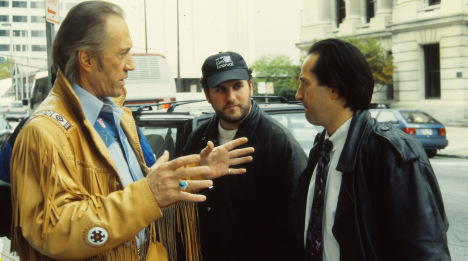

David Carradine, Myself, Michael Maloney. “American Reel”.

David Carradine, Myself, Michael Maloney. “American Reel”.

My first true “Hollywood lunch” was the day I met David Carradine and his then-fiance’ Marina Anderson at the The Bistro Garden in Studio City. By the time we got to the point of our meet and greet, the producers and I had already had many lively discussions about whether or not David was the right actor for the role. He had quite a long and storied history of issues, both on and off-set, and although we had a “first time director” (I had been directing for years, just never a feature-length film), I was coming in hot off of a win at the Sundance Film Festival for “In the Company of Men”, and I had some momentum. David was an established, albeit tarnished name in film & television, and he really wanted to do our film. We had already gone through an exhaustive list of other potential candidates, some of which would certainly have made the soundtrack worth a lot more, but David made the investors happy because he was a known quantity for overseas sales. This meeting was really set up by the producers to convince themselves and me that he was worth the gamble.

It’s hard to find the words to describe the way I felt there that day, meeting a bona fide movie star at a Hollywood restaurant to discuss a movie deal. David Carradine was, in my mind, Hollywood royalty. Everyone knew who he was, and whether they were fans or not, the fact that you were doing a film with someone like him meant that you were legit. I’d like to say that I was cool, calm and collected through the whole process, but the truth is I was scared out of my mind. What if he figures out I’m a phony? What if he bullies me out of my job, just because he can? When you’re trying to get your first feature directing gig, you can’t help but feel like a phony, because nothing you have ever done before that can truly prepare you for what is about to come. I knew that someone like David Carradine could see right through me, so all I could do was be as honest and confident as I could. What I didn’t realize at the time was just how much clout I really had in that situation. As terrified as I was, David wanted to do the film more than I or the producers wanted him to do the film. It was his audition to lose.

Music was a major part of the discussion, and that was where I still needed convincing. The main character of the film had to be able to act and sing. The other candidates for the role that were still in the running were all professional recording artists, but not bankable movie stars. Sure, they could all act, but they weren’t names that would sell a movie. We had migrated back to David because he was the latter. What we weren’t convinced of yet was whether or not he could pull off the music.

Don’t ask me how we got onto the subject of crossing lyrics between songs, but we did, and somehow I ended up issuing David the challenge of singing the lyrics of “Amazing Grace” to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun”. I’ll never forget the way his demeanor changed in that instant. I believe that was the first bond I formed with him, at that moment of impact where I saw the creative spirit in him come alive. David Carradine was an intimidating presence in every way, but at that moment I looked across the table and saw a kid, giddy with a challenge. His eyes lit up, the gears turned quickly, and he looked playfully back at me with a subdued smile.

At that, he got up from the table, walked over to the baby grand piano in the middle of the restaurant, and promptly sang “Amazing Grace” to the tune of “House of the Rising Sun”. He sat for a moment when he finished and pondered it, then came back over and sat down. I looked at the producers, they looked at me. I looked at David. “You ARE James Lee Springer!” I said to him, without hesitation. David smiled, looked back at me and said, “yeah…I know!” And with that, David Carradine became James Lee Springer, the movie’s lead character, and “American Reel” began its journey into the abyss of independent film production. The next time I would see David would be the night before principal photography began, when the first shock of working with him would hit me – right in the ears.

…to be continued…

Share this: