I resolve to exercise more

Intent is the birthday present you will buy, the New Year’s resolution you will make, the vacation you will take in the summer of 2018. Intent is the brilliant child of the future, yet whenever something goes wrong—and it does so frequently—we point at the negation of our intent as the devil and the dark excuse of the far past: I hadn’t intended to hurt you, I hadn’t intended to be a bad person. No one intends to be a “bad person”.

In terms of type:

There’s grand intent—that requires thought, preparation, effort, time, and that is usually well-justified within our internal system of values.

There’s habitual intent—that requires only repeating circumstances and that once well-justified is rarely reexamined.

Then, there’s muddling through.

Habit is the mainstay of life, whilst grand intentions are rare (those well-thought out and actionable, even rarer). Which leaves muddling: these are the chance encounters, the unplanned stops, the out-of-stock labels on your favourite items; this is when you forgot a change of clothes or your wedding ring. Whenever Murphy’s law strikes, we muddle. Depending on what comes of it, we ruminate on what was intended—few people will admit to have been guided purely by circumstances, chance, or biology (unless they’re determinism diehards), but will instead claim step-by-step determination.

Unless it’s a crime.

Freddie Montgomerie, the protagonist in John Banville’s The Book of Evidence, bludgeoned a girl to death while stealing a painting (not a spoiler, part of the book blurb). In the Quote, Freddie reflects on (the lack of) his murderous intentions. Notice how he weaves undeniable evidence with a psychological defence of his state of mind: claiming he reacted to the circumstances, claiming he was unaware of the edge between no-intent and intent, claiming control had been wrenched from him by somebody else inside him.

Quote: I killed her, I admit it freely. And I know that if I were back there today I would do it again, not because I would want to, but because I would have no choice. … Nor can I say I did not mean to kill her—only, I am not clear as to when I began to mean it. It was flustered, impatient, angry, she attacked me, I swiped at her, the swipe became a blow, which became the prelude to a second blow—its apogee, so to speak, or perhaps I mean perigee—and so on. There is no moment in this process of which I can confidently say, there, that is when I decided she should die. Decided?—I do not think it was a matter of deciding. I do not think it was a matter of thinking, even. That fat monster inside me just saw his chance and leapt out, frothing and flailing. He had scores to settle with the world, and she, at the moment, was world enough for him. I could not stop him. Or could I? He is me, after all, and I am he.

—John Banville, The Book of Evidence, (1989)

Where does spume end and seawater begin? Where doesn’t circumstance give birth to intention?

Thinking on a smaller scale, if we muddled through well—we take credit; if we muddled through badly, we often justify our petty “crimes” in those terms: reaction, unclear intention, slipping or lack of control. And it bothers us little, except when we look closely at the two issues raised in the last sentences of the Quote: free will and integrity of identity.

You would think that such hefty philosophical issues might require hefty linguistic structures. They don’t; they just each require a slightly different application of a chiasmus (a parallel structure that inverts two words).

- I could not stop him. Or could I? This gets at free will through expressing doubt, cynicism, regret by the simple inversion present in a rhetorical question. (The chiasmus disunites.)

- He is me, after all, and I am he. This brings up the question: are we the same person across time and space and action, even if we’re physically contained within the same body? Since language, unlike mathematics, does not necessarily utilise to be as a symbol of equality but rather as that of attribution, Banville applies it twice, once in “each direction”—for emphasis. (The chiasmus unites.)

Compared to more florid and clever rhetorical examples for which chiasmus is usually known (such as the oft cited one by John F. Kennedy Mankind must put an end to war—or war will put an end to mankind), Banville’s two applications are pedestrian. But they work to ask the big questions, and their variations could easily work for any other writer to a similar purpose, especially as an apotheosis of self-reflection.

Returning to the initial theme: I came across two more quotes that describe this edge between no-intent and intent in distinctly different language.

If in 1989, Banville’s protagonist splits the hairs, then in 1952, Anthony Powell’s protagonist offers a general statement on the deceptiveness of retrospection.

Nothing in life can ever be entirely divorced from myriad other incidents; and it is remarkable, though no doubt logical, that action, built up from innumerable causes, each in itself allusive and unnoticed more often than not, is almost always provided with an apparently ideal moment for its final expression. So true is this that what has gone before is often, to all intents and purposes, swallowed up by the aptness of the climax; opportunity appearing, at least on the surface, to be the sole cause of fulfilment.

—Anthony Powell, A Buyer’s Market (1952)

If in 1952, Powell expresses the deceptiveness of retrospection due to lack of insight into life’s complexities, then in 1890, Oscar Wilde expresses the deceptiveness of a supposed will or intention by attributing both to chance.

Life is not governed by will or intention. Life is a question of nerves, and fibres, and slowly built-up cells in which thought hides itself and passions has its dreams. You may fancy yourself safe, and think yourself strong. But a chance tone of colour in a room or a morning sky, a particular perfume that you had once loved and that brings subtle memories with it, a line from a forgotten poem that you can come across again, a cadence from a piece of music that you had ceased to play—I tell you, Dorian, that it is on things like these that our lives depend.

—Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890)

The beauty of it: all three quotes pass as plausible because literature accommodates many versions of the truth.

Wilde’s description of chance speaks clearest to me, which, perhaps, says something of my nature. Whose version of muddling through life do you identify with most?

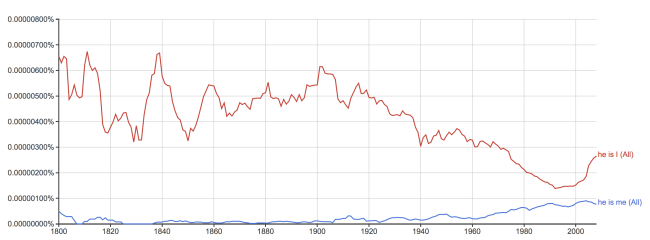

P.S. Banville’s enallage (incorrect grammatical usage of he is me) made me look up the frequency graph of he is I (red line) versus he is me (blue line) on the Google Ngram Viewer. Can anyone guess what’s bringing on the surge of grammatical correctness post 2000?