Buying books is great, period. The ruffle of new pages and fresh ink. The creak of an untested spine. The velvety texture of untouched paper. The intrigue of an undiscovered world only hinted at in the blurb on the back. The hush of the store, usually an oasis of calm in a sea of shopping centre din. The weight and feel of a book about to become your own.

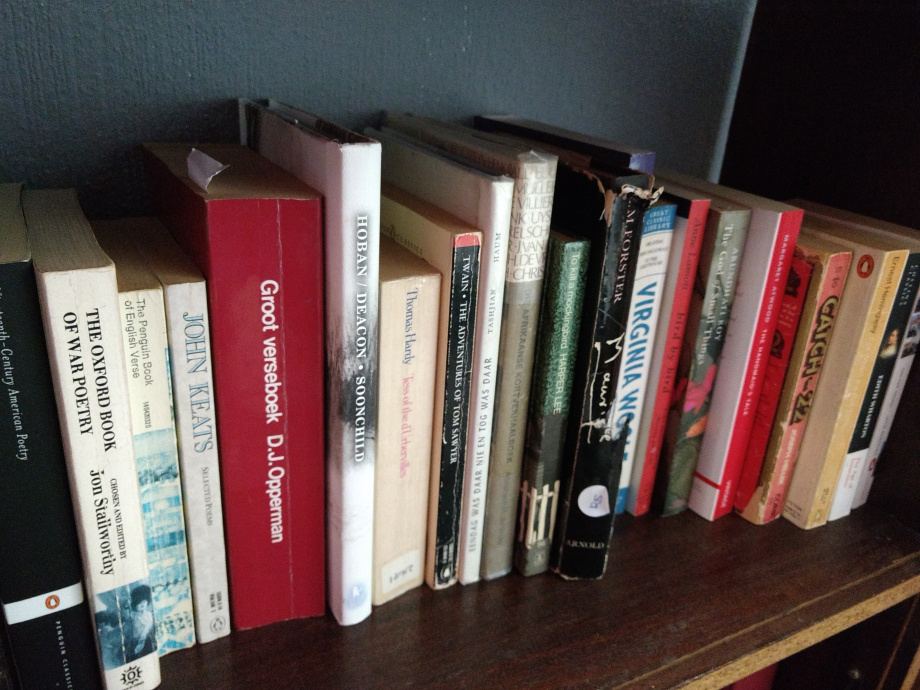

If buying new books is an adventure, then buying old ones is a mystery. The dusty air and narrow corridors of your typical secondhand bookshop lend itself well to an atmosphere of the unknown, the puzzling and the uncanny. Books, once new, now curl and rustle with age. Their smell sours. Their covers are tarnished with dirt, their once glossy titles pitted and scratched. Their pages are dog-eared, sometimes scribbled on, often thickened with the spill of some unidentifiable liquid. Names and dates adore title pages. The book’s spine has been cracked, once, twice; pages threaten to spill out and seek solitary solace.

The books themselves can be any and often every genre; a secondhand bookshop does not discriminate. Bestsellers share shelf space with obscure titles. Westerns and YA lit regard each other uneasily from across the room. Classics leer at Danielle Steeles. The surplus Dan Brown and Stephenie Meyer novels prove that even as forgiving a market as the book market has its limits.

Yet the books themselves aren’t the end of the mystery. Their histories are an intrigue on their own. Where, one wonders of the Afrikaans poetry volume warped with green-tinted water, did you sit before you came to my shaky little bookcase? And you, William Golding volume, practically unopened and probably never read – who were you an unwanted Christmas present from?

Sometimes the books will share some of their secrets, yet these only deepen the mystery rather than resolving them. Old letters, cards, newspaper clippings, donation slips, brochures, even photographs will often tumble from an old book’s pages. Proving, perhaps, that readers are an inventive sort: anything can be used as a bookmark. Some of the secrets shared are lively. A book about prayer hinted at a woman’s early history, from her beginnings as an eager student enthusiastically involved in church activities, to her stint in the military and her marriage (dutifully reported in the local paper, the clip laminated and saved).

Other secrets are not as happy. I remember a book lovingly inscribed to a husband. It was filled with various birthday and Valentine’s Day cards and other romantic notes. In one, the wife thanks him for an exercise machine he bought her. Her handwriting is big and bubbly, with hearts dotting her i’s. Where are these spouses now, that such a large chunk of their relationship could be abandoned in the annals of a secondhand bookshop?

Not inappropriately, secondhand bookshops are filled with a thousand stories. The march of old children’s novels and academic textbooks tell their tales of growing up, the fantasies changing from knighthood and solving mysteries to more practical subjects like computer engineering and mathematics. The diet and exercise books are always either over or underused. Recipe books often come splattered with a sampling of the recipes they contain, their spines beholden to a family’s favourites. There are gardening books for all seasons; history books too historic; outdated travel guides to other places: Europe and Asia and the Cape. Foreign languages languish without someone to keep learning them. And the religious section – filled with shelves and shelves of daily devotionals, old hymnals falling apart at the seams, their songs now unsung, and small inspirational hardcovers that, if their sheer number is any indication, failed to inspire.

People may wonder how I could spend hours browsing a used bookstore. It smells funny, they may say, and they’d be right. It’s too dirty, they may point out, and I wouldn’t argue. But while my hands become sticky with the grit of books who’ve lived real lives before I met them, I’m also thinking about the person (“M de Jager”) who donated their entire Anne Rice collection to our SPCA’s charity bookshop. The novels are old, unglamorous paperbacks with yellowing pages and thick, outdated typeset almost as cheesy as their content. What, I wonder, happened between this person and Anne Rice’s vampires? Was the breakup sudden, or was it a long time coming? What replaced these books, if anything?

But as I turn Interview with the Vampire over in my hands, most of all I wonder this: where oh where will I find space for all these books in my house? It remains the deepest mystery of all.

Advertisements Share this: