By KATE FORSYTH

This week Vasilisa the Wise & Other Tales of Brave Young Women is finally launched into the world.

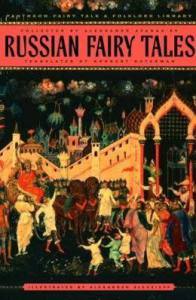

To celebrate I thought I would explore the history of the titular tale, which is one of the best-known and best-loved Russian fairy-tales. An old oral tale, it was transcribed by Alexander Nikolayevich Afanasyev between 1855-67 and first published in his collection, Russian Fairy Tales.

There are many different versions of the story, many of which are called ‘Vasilisa (or Vassilisa) the Beautiful’. I deliberately chose the title which did not focus on the heroine’s beauty but rather on her wit and wisdom.

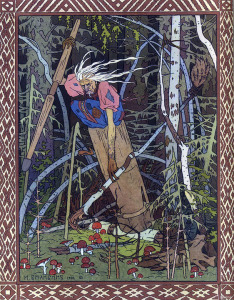

In nearly all of the tales, a young woman is sent by her cruel step-mother to fetch fire from Baba-Yaga, a terrifying witch who lives in the midst of a dark forest and rides about in a giant iron mortar (a bowl for grinding food), which she steers with a pestle (the grinding tool).

Baba-Yaga lives in a house with chicken legs and is known to eat children. The hut has a life of its own. It walks about, spins in circles, and emits bloodcurdling screeches. A fence made of human bones surrounds the hut, topped with skulls whose blazing eye sockets light up the forest.

There are many stories about Baba-Yaga in Slavic myths. The very earliest ones refer to her as ‘Snake-Baba’. In pre-Christian mythology, snakes were not seen as evil. They were instead powerful emblems of rebirth and transformation, since they shed their old skins for new. Snakes was therefore seen as wise and powerful beings that had much to teach about the natural cycles of time and the seasons.

It is thought that the term ‘yaga’ is a corruption of the Russian words ‘uzkii’ which means ‘narrow’ or ‘snakelike’, and ‘uzh’ which means ‘grass-snake’, both developing from the Old Slavic word ‘ужь’.

The same old Slavic word led to the Latin words ‘anguis’ (snake), ‘anguinus’ (pertaining to a snake), and ‘angustus’ (meaning to squeeze or tighten like a snake), which interestingly enough also led eventually to the English word ‘anguish’.

The word ‘baba’ is linked to ‘babushka’, which means grandmother, but in its shorter form means simply any woman, young or old.

So in the earliest tales, Baba-Yaga is not a figure of evil, but rather a wild, dark, wise figure whose role is to help the heroine change and grow.

Once upon a time, older women were seen as ‘crones’, the keepers of wisdom and tradition for the family or clan. These wise women were thought to understood the mysteries of birth, life and death. Often they were healers and midwives, who brought babies into the world and cared for those who were dying.

Baba-Yaga contains within her these wise old women, as well as later ideas of witches as ugly and evil.

Her links to nature and the cycle of time are emphasised by her servants, the White Horseman, the Red Horseman and the Black Horseman, who she calls, ‘My Bright Dawn, my Red Sun and my Dark Midnight’ because they control daybreak, sunrise, and nightfall.

Vasilisa comes to her hut searching for fire, which symbolically means the light of wisdom. She has to endure a series of trials and tribulations, but is helped in her quest by the little wooden doll given to her by her dead mother. The doll symbolises the ancient maternal wisdom of the crone, but is also Vasilia’s own intuition, helping her find her way.

Dr Clarissa Pinkola Estés interprets the story of Baba-Yaga in her seminal work on fairy-tales, Women who Run with the Wolves. She wrote:

To my mind, the old Russian tale “Vasalisa” is a woman’s initiation story with few essential bones astray. It is about the realization that most things are not as they seem. As women we call upon our intuition and instincts in order to sniff things out. We use all our senses to wring the truth from things, to extract nourishment from our own ideas, to see what there is to see to know what there is to know, to be the keepers of our own creative fires, and to have intimate knowing about the Life/Death/ Life cycles of all nature – that is an initiated woman.

Stories with Vasalisa as a central character are told in Russia, Romania, Yugoslavia, Poland and throughout all the Baltic countries. In some instances, the tale is commonly called “Wassilissa the Wise.” I find evidence of its archetypal roots dating back at least to the old horse-Goddess cults which predate classical Greek culture. This tale carries ages-old psychic mapping about induction into the underworld of the wild female.’

I certainly see the tale as one of female liberation. Vasilisa journeys from a position of childlike submission to one of strength, wisdom and independence. The little wooden doll advises and supports her, but Vasilisa herself must choose what actions to take.

Step by slow step, she turns from a girl into a woman. She sheds her old skin and is reborn.

Advertisements Share this: