*Contains spoilers*

The first time I ever watched ‘The League of Gentlemen’ was on the night of its television debut – BBC Two, 10pm on the 11th January 1999. The date is burned into my memory in the same way as I’d never forgotten accidently stumbling upon a late night TV screening of ‘The Wicker Man’ whilst channel hopping back in the mid-1990s. Seeing Edward Woodward in police uniform at the village school investigating the disappearance of a schoolgirl I was initially lured into thinking it was a straightforward police procedural drama until Sergeant Howie and Miss Rose’s conversation turned to Celtic paganism, phallic symbolism and maypoles. Suddenly it became uncomfortable, strange and unpredictable and quite unlike anything I had seen before.

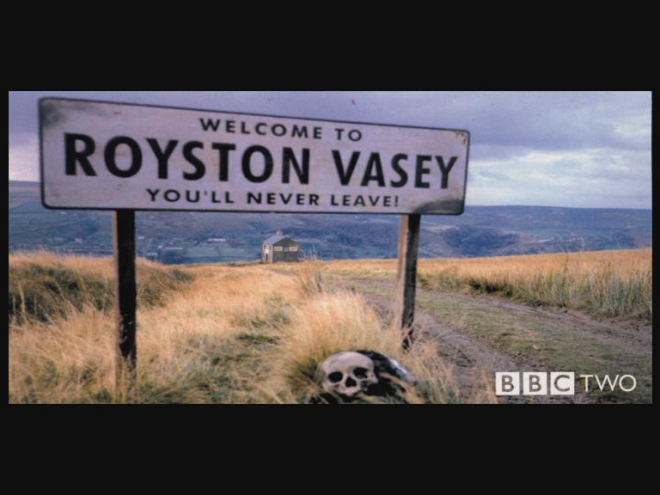

‘The League of Gentlemen’ was similarly revelatory but even more so: The unsettling interbred look of Tubbs and Edward, their reactionary attitude to the outside world and the flashpoint moments when outsiders intruded into the ‘Local Shop’; the strongly evocative Ken Loachian feel of the Restart room where Pauline systemically bullied and brutalised despondent jobseekers; the perturbingly strange Denton family, where unorthodox beliefs and behaviour were at the extremes of bizarre and pushed by fantastical degrees even further; social observational realism as the starting point in the Geoff, Mike and Brian triumvirate relationship and their competitive, toxic masculinity; the surreal, twisted inversion of the ‘All Creatures Great and Small’ motif. All of this and then the final scene of episode one really hitting home: The Scottish burr of policeman Bobby Woodward, the local shop proprietors being questioned about the disappearance of rambler Martin Lee: It was Sergeant Howie facing recalcitrant locals reimagined and appropriated into the fictional small northern town of Royston Vasey.

Elemental counterpoints (civilisation versus savagery, rational versus irrational) dark themes exploring cruelty and the fallibility of human nature, an array of references and influences (from horror films to fly-on-the-wall documentaries) inspired, original writing and consummate, nuanced acting were all fused together to create something highly distinctive and unique. ‘The League of Gentlemen’ had arrived. The disparate elements seamlessly worked together. It was the exceptional sum of all its parts.

The three series of ‘The League of Gentlemen’ and the standalone Christmas Special had a dynamism that was mesmerising, intoxicating, thrilling. It was unlike anything seen on television before, certainly not comedically. Creatively it was something that only comes around once every generation. Its impact was indelible and groundbreaking and it changed the landscape of British culture. The writing was striking, its acting exceptional, it had an edge to it. The emotional depths reached and the interplay of a wide range of influences that were brought into it made other comedies, especially sketch based ones, look amateurish and one note. This was a television programme where a laugh could become a scream in an instance, which ran the risk of laughter turning to dust within a space of a scene, where a smile might change to a gasp or the prick of tears in the eyes. The tension held between the two, the laughter and the bleakness, created a feeling of uncertainty which left you wondering what was coming next. Would your emotions be pounded or find relief and release? The alternating, shifting tones nevertheless held together as an overarching and cohesive creation.

The fictional town of Royston Vasey invoked the notion of the countryside as a threatening place, a repository for the dark underbelly of parochialism that can fester there – insularity, narrowness, separatism, localism and the fear of the outsider, of ‘otherness’. It represented rurality as bubonic not bucolic. Royston Vasey was a place which functioned almost as a character in itself. It encapsulated a certain kind of small town mentality as a residue for desperation, brutality, ferality, anger, despair, failure. It was a space where eccentricities and oddities took root, where weirdness and strangeness were part of the landscape and the everyday high street. The surreal juxtaposition of images in the visual jokes of the opening titles, which featured in each episode of the series, was a condensed illustration of this. Royston Vasey’s location was also cognizant of an identifiable, post-1970s economic and cultural phenomenon – the northern town as a place of decline and decay, whose inhabitants lived lives on the periphery, abandoned, neglected and forgotten. The furrows of folk horror and rural gothicness in the show bled into all of this. ‘The Wicker Man’ was used as the obvious starting point but other horror film references were mined and dispersed into the mix, as well as a general affinity for the macabre.

The League themselves were informed by a northern sensibility but one that defiantly struck out against northern miserabilism, the clichéd, sterile and restrictive stereotyping that embraced and overemphasised deprivation and ‘northernness’: Legz Akimbo’s ‘No Home 4 Johnny’ in S2 and ‘Scumblina’ of the Local Show tour being prime examples. Instead, it was Alan Bennett and Victoria Wood who were key influences, most tellingly on the naturalistic, social observational areas of their writing. Cultural minutiae, social embarrassment and awkward interactions are all there in the resonances suggested by the colloquial detail of the particular choice of words and the specificity of brand names (“I love my little soaps, Iris. Eden au Lac, Montreux. The Inn at the Mystic, The Dan in Haifa” – Judee Levinson; “I’ve been washing my hair with Fairy Liquid for the past fortnight” – Pauline Campbell-Jones) It is there in the frayed melancholy of characters’ curtailed ambitions and the small sadnesses that attach to them (Les McQueen, Geoff Tipps)

One significant aspect of ‘The League of Gentlemen’ that made it so singular and unusual and helped secure its deserved reputation was the dramatic depth and emotional truth reached by its characters. It was unheard of in sketch comedy, atypical within the half hour comedy format and unparalleled given the range and number of characters involved. That a significant number of the characters were grotesques – in behaviour, attitude, temperament, and in a few cases, even physically – made their humanising even more extraordinary, given they initially appeared to be monstrous and appalling. Mark Gatiss, Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith are remarkable actors. That they wrote the material too, alongside the non-acting Jeremy Dyson, meant the level of understanding and connection to the characters they portrayed was there from the start. They knew them inside out and were therefore able to bring between-the-lines subtextual reverberations to the scripts. This foundation helped to finesse nuanced levels of empathy and pathos and create dimensions of feeling through the slightest of tonal shifts in the performances. The actors’ inherent knowledge of their material breathed multi-layered subtleties into the characters that went beyond the superlative quality of the writing.

‘The League of Gentlemen’s sketch-dominated format for series one and two never worked in a straightforward way. In a reversal of the usual sketch show based approach, the sketches were always there to serve the characters, not the other way round. This was due to The League’s focus being on character comedy. Series one and series two deployed episodic narrative structure, making the sketches work more like scenes, with a loosely built-in story arc for the main character pairings or groupings. The sketches were more akin to devices that revealed the characters’ interrelationships within each of their groupings – Pauline, Mickey and Ross, Geoff; Mike and Brian; Iris and Judee. They weren’t about always working towards a punchline or needing to punctuate a scene with a catchphrase. Scenes built and developed stories that had a defined trajectory within each set of characters that ran parallel to each series’ main through-plot. The sophistication, intelligence and strength of The League’s writing was self-evident from the start.

If there is one aspect that all of Royston Vasey’s characters share it is failure. They are trapped by their own inadequacies – it’s the essence of who they are and the basis for the comedy and the pathos that come from them. Pauline was glaringly unsuited to helping the unemployed find work; Geoff hated his job and knew he was no good at it; Ollie’s ‘issue based’ plays only succeeded at being both inappropriate and offensive; Les McQueen couldn’t let go of his dream of finding a way back into the music business even though Crème Brulee were only third rung journeymen to begin with. Failure often manifests itself in malevolent behaviour as an outlet for discontentment or unhappiness and this was startlingly apparent in the League’s characters: Pauline’s bullying and casual cruelty, Geoff’s endemic anger, the fits of rage in Ollie. Likewise, feelings of disappointment and regret can evoke undertones of melancholy and bleakness, which are woven right through ‘The League of Gentlemen’.

The extremes of behaviour on display – viciousness, brutality, pitilessness and the sometimes mournful quality and sense of sadness which is palpable across the three series is what makes the show so brilliantly dark. Bleakness runs right through it like a draught in a morgue. Thematically it’s as jet black a television series as has ever been. It grew a shade darker with each series, culminating in the blacker than a raven’s ring dipped in molasses of series three. Over the course of three highly memorable series, subjects such as poverty, pederasty, infant death, anorexia, suicide, necrophilia were layered between every depiction of human failing and frailty it was possible to portray.

Fans and admirers of the series and of its four extraordinarily gifted creators kept the memory of the show close. What it meant to them became, if anything, stronger the further away in time it grew. Partly this was nostalgia for something that was loved and adored but it was also down to Jeremy, Mark, Steve and Reece maintaining such a fertile level of productivity, professionally and creatively. Their imaginations remained as prolific and potent as ever.

As it neared the 20th anniversary of their BBC debut, the Radio Four series ‘On the Town with The League of Gentlemen’, the quartet made an auspicious and very welcome announcement – they were back writing again for an anniversary TV special of ‘The League of Gentlemen’.

When they reunited to write over the summer the material poured out of them (according to Reece Shearsmith) so much so that they wrote far more than was needed for an hour long special. The result was that fans were instead blessed with three new half hour episodes – The League of Gentlemen Anniversary Specials.

Anniversary Specials: 1: Return to Royston Vasey

“Apparently there was a place called Sodom which was full of incense, buggery and murder. Eventually it was destroyed. Shat on by God from a great height. Welcome to Royston Vasey.” (Bernice Woodall Mayor of Royston Vasey)

Episode one of The League of Gentlemen Anniversary Specials starts with a direct reference to the beginning of the very first episode in 1999: Benjamin Denton is reading a letter on a train as a voiceover recites its contents, only for the camera to pull back and reveal a nosy old lady is sitting next to him reading the letter aloud. Linking back to the genesis of the TV series, when the camera pulls back this time we see a nude Val Denton talking as Benjamin tries to focus his attention on his phone. A series one reference is overlaid with a series two reference to the Denton’s ‘Nude Day’. However there is something different about Val – the merkin has grown ever more hirsute, it’s now of feral proportions and her breasts have sagged noticeably.

In the time it has taken to watch the opening joke the intent of The League of Gentlemen Anniversary Specials has been set: A scattering of nostalgic abstractions, some self-referential nods to fans’ knowledge of the three series and the characters’ backstories integrated with a narrative thrust that firmly establishes us in the present, a present that resonates around the vicissitudes of ageing, decline and the unforgiving march of time.

It is essentially the same but also different as the changes are most definitely rung for nearly every character as we’re reacquainted with them one by one over the course of the episode. “I think we felt that if it felt like it had just come back on again, it had never been away, that would be the best feeling about it” (1) (Reece Shearsmith) However the League were adamant that a simple ‘greatest hits’ retread would have never satisfied them.

The evocation of the passage of time is reiterated when local journalist Ellie arrives in the town and proceeds to walk along the high street. The town itself is redolent with decline and decay. Royston Vasey’s name sign is covered in dirt, piles of rubbish bags and an old mattress lie outside the railway station and most the shops are boarded up – cue a slew of sight gags. Then there are the food banks, including a literal one in the form of an ATM dispensing sandwich fillings. We are unmistakably in the contemporary Britain of 2017.

We briefly reunite with Iris Krell before she vanishes into thin air after going inside a newly unveiled photo booth on the high street. The mystery of the photo booth, from which its patrons disappear almost as soon as they enter, is one of the two through-stories which are linked across the three specials. The other being the threat is to the very existence of Royston Vasey with the proposed moving of the boundary line to incorporate it into one of the nearby bigger towns, making it locally and cartographically extinct by completely erasing it from the map. Mayor Bernice Woodall un-altruistically mounts a campaign to save it when she learns this will mean her free care parking space will go.

One of the main narrative functions of ‘Return to Royston Vasey’ is to re-establish the audience with the town’s characters. These are made up of either vignette revisits or a more deeply sustained look inside their lives with story arcs taking us on character’s journeys beyond this first episode. The one-stop returns – Mr Chinnery’s veterinary surgery has stayed open for bloodletting business; Henry and Ally remain obsessed with films; Herr Lipp’s pederasty still engenders double entendres as an expression of his creepy proclivities; Barbara, the transsexual cab driver is now immersed in the vocabulary of today’s cultural politics, assailing her customers about the use of appropriate gender neutral terms and the notion of safe spaces with proselytizing zeal. The script beautifully delineates these characters in their fleeting returns. The brief excursions to illustrate ‘where are they now’ are delicately balanced between acknowledging the intervention of time and in a couple of cases, notably defying it. Herr Lipp and Chinnery appear untouched by the passing years, satisfying audience expectation by staying exactly the same.

Mr Chinnery and the exploding hedgehog was a perfectly worked unsettling trip down memory lane, that disorientating juxtaposition of the detritus of animal remains within the comforting setting of ‘All Creatures Great and Small’. The carnage of spiny remnants skewering the faces of a mother and daughter, the tension ratcheted up with the queasy insertion of a children’s nursery rhyme ‘Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star’ to delay the cathartic release of expectation fulfilled was signature League of Gentlemen, timed and executed to perfection.

With Henry and Ally the passing of the years meant inevitable change and one that felt slightly sad. Obviously middle aged but psychologically still somehow infant man-children, the pair, now trying to flog black market DVDs to indolent teenagers, seemed stuck in the past, clinging to their youthful obsessions and unaware of how much time had moved on. It was melancholic and a scene which subtly alluded to The League of Gentlemen Special’s all-encompassing theme of mortality.

The remaining characters have journeys to go on, ones which begin with the meticulous layering of changed circumstances. The Denton’s scrupulously ordered, highly regimented and hygiene-obsessed domain has degenerated into a chaotic, disordered rubbish tip. The home is low lit with the production’s sublime photography enshrouding it in oppressive dark shadows, evoking a sense of mourning hanging heavily over it. Their house has run down and been diminished by familial loss, Benjamin having returned to Royston Vasey to attend his Uncle Harvey’s funeral. Benjamin’s underlying unease is considerably increased with his reintroduction to the Denton twins. Now adults, they still speak in unison, finish each other’s sentences and radiate a spookiness that easily suggests an imitate knowledge of grimoires and a facility for casting spells.

Al, one of the sons unfortunately cursed with having Pop as a father, is now married to Tricia, who we met back in S2, where she was molested and frightened away by Pop during an excruciating family meal. Pop is the behemoth of Royston Vasey, utterly irredeemable and through Steve Pemberton’s extraordinary performance given the fullest expression of the dark soul of humanity. His unwelcome return into Al’s life is heralded in gothically dramatic fashion, with Pop turning up on Al’s doorstep at night as a storm rages, a metaphor for the troubled emotions and deeply buried memories that Pop’s reappearance stirs in Al. The look of shock on his face as he sees his father for the first time in years says it all.

Returning to the trio of Geoff, Mike and Brian to see how life had treated them in the intervening years was the comic highlight of ‘Return to Royston Vasey’. The fissures, strains, stresses and shifting allegiances in their relationship had always been superbly conveyed over the three series and continued here unabated. Brian’s life has remained one of middling success which aligns perfectly to his inoffensive, middle-of-the-road, somewhat ineffectual personality – he’s now a manager in a building society. Geoff, the perpetual loser has got fatter and is now trying to deal with his reduced circumstances of part-time employment, appealing to Brian that he’s “on the bones of his arse” as he desperately embellishes an absurd business plan that is rejected as soon as the proposal leaves his lips. He’s still devoid of the basic sensitivities and social skills needed to successfully negotiate someone through life. Even Mike’s life has taken a turn for the worse. Geoff tells Brian, with a touch too much glee, that Mike’s wife Cheryl is now morbidly obese and bedbound. The scene ends with Mike asking Geoff to kill his wife and Geoff, without missing a beat, agreeing to it. This brilliantly sustained and hilarious scene appears to be almost effortless because the laughs are generated and arise purely from the characters. There is a flow, tempo and cadence to it which is naturalistic and wholly convincing. From the character continuity of Geoff’s complete lack of self-awareness to the quietly exasperated reactions of Mike and Brian, it articulated a truth about the chasm between deluded self-image and reality and the patient tolerance of unspoken friendship. All of that is there and more in the Geoff, Mike and Brian relationship. It is nuanced, inspired and peerless work, a beautifully define and finely honed comic creation.

For some fans the re-emergence of Tubbs and Edward in the closing minutes of the episode was the most eagerly awaited character revival of all. They have an iconic status beyond the show itself that has that on a resonance due to the current Brexit situation. The characters seem to have anticipated – and now practically define – a version of the narrow parochialism that has affected recent public discourse. Bearing the facial scars from the fire which engulfed the Local Shop when it was burnt down by an irate mob at the end of S2, Tubbs and Edward have been reduced to living as squatters in a condemned council flat and have even, rather pathetically, constructed an infantile version of a pop-up shop in their dimly lit lounge. From the outset of council worker Lyndsey and journalist Ellie’s fateful encounter with them it is clear that the Tattysyrup’s are as unreconstructed localist as ever, to the tips of their pig-like noses, with Tubbs still positively antediluvian (“dockalments”) They haven’t changed but rather, as almost prophetic conduits, their mindset now connects to and articulates the mood of the age. Edward’s instruction to Tubbs to “get undressed” at the close of episode one is like a hypnotist’s trigger – debauchery and torture are sure to follow. Any outsiders unfortunate enough to have crossed their path are now destined to become mere numbers on a long list of victims.

Nothing prepares you emotionally for the scene involving Pauline. At the start it feels like time has receded because nothing appears to have changed. She is back as a Restart officer with Ross and Mickey as returning jobseekers. Knowing her, Ross and Mickey’s complex tripartite relationship it’s a confusing set up, a denial of everything we know about their complicated backstories. We wonder what the League are doing – it’s as if we’re watching an outtake from series one, even though we clearly know things have moved on in Royston Vasey. And then the rug is pulled from under us. What the audience is watching is a session of Pauline’s reminiscence therapy – she is suffering from dementia. It is a moment which takes your breath away. All at once the scene has metaphorised into something completely different and it is heartbreakingly poignant. The decision to approach and touch upon this subject is a brave and daring one and it is quite brilliantly done. Mortality is brought to us head on and there is no hiding place, no small crumb of comfort to be found. One of the series’ most vibrant, multi-dimensional and strangely sympathetic characters has been felled by a disease which destroys the person from the inside, where their personality fades away until they’re an empty shell of what they once were. To condemn a character as memorable as Pauline to this fate makes the scene one of the most starkly tragic and extraordinary things the Gentlemen have ever written. Those little details – the empty box of Pauline’s pens, the way Mickey earnestly mimes picking up a pen in an attempt to somehow help his wife, the moment when Pauline stands alone, lost and confused in the corridor – make you inwardly gasp.

What is most strongly evoked in episode one of the Anniversary Specials is a strong sense of decline. The multi-layered script blends several important elements together – the re-establishing of the characters in the present, the initiating of arcs, whilst also providing space to revisit other characters in brief and memorable ways. The pace is impeccably controlled and the scenes beautifully structured. The script also elicits a powerful undercurrent of mortality, a subtle feel for the unforgiving nature of time and this is deftly carried forward into the second episode as well. What is induced is an almost reflective melancholy, more pronounced than ‘The League of Gentlemen’ has been before. It is what helps to set these Anniversary Specials apart as something substantial, meaningful and far beyond the perimeters of a simple exercise in nostalgia.

Anniversary Specials: 2: Save Royston Vasey

One initial reunion with the characters was the focus of episode one. It brought the present circumstances of their lives into sharp relief, introducing a thematic that coalesced around decline, mortality and the unremitting march of time. With the second episode we move with precision and beautifully timed beats between characters’ arcs established in episode one as they’re further developed. ‘Save Royston Vasey’ is also distinguished by a narrative which mediates between reality and a separation from it, one in which occurs stories, fantasies and distancing techniques are used by some of the characters as a way of coping with the disappointments, tribulations or emotional pain in their lives.

As creative statement of design sees the episode open with a dream sequence as we’re reintroduced to Ollie Plimsolls, the permanently aggrieved theatre-in-education self-styled writer, director, actor. He uses the artistic triumphant of a fantasy Olivier Award win to settle old scores in an acceptance speech, as 20 years of embittered resentment and acrimonious lack of professional success is tumultuously played out in his unconscious mind. This reverie is broken by someone telling him he has a class with Year Nine. The sad reality of Ollie’s life is that he is now a drama teacher in a secondary school. A close-up on his face as he wakes up and finds himself back in his diminished real world shows it etched with the weary look of someone who’s been disappointed by life, a sadder and more quietly acquiescent man than the persona in his dream.

Later in the episode when Ollie arrives to take his class he appears to be a beloved teacher, practically hero-worshipped by the roomful of 13-14 year olds and full of the same hyped enthusiasm he had when he led Legz Akimbo. So adored is he as a teacher his pupils have secretly arranged a reunion of Legz Akimbo with Phil Procter and Dave Parkes to mark Ollie’s retirement from teaching. The theatre troupe perform a typical excruciatingly bad play, where the difficult ‘issue’ of child abuse is handled with appalling bad taste and cack-handed ignorance (the word ‘peadophile’ unfurled on a banner across the stage being one of the many low high points)

As the scene progresses the gap between the implausibility of what we are witnessing (cheering pupils chanting ‘Sir’, Dave and Phil keen to reform Legz Akimbo and go back on the road) and believable, credible reality is stretched beyond limits until Ollie finally realises it’s still a dream (the conceit sustained across several scenes) The dream has been a way of delaying the immediate reality of an impending class with his unruly, uncontrollable class who care so little about him they barely acknowledge his existence except to throw insults. In a brilliant, silent piece of acting by Reece Shearsmith, the physically diffident and nervous way Ollie steals past his pupils is a sad contrast to the bounding, confident physicality in his dream. Another close-up on Ollie’s resigned yet haunted face as he stands in front of the class contains an even sadder, deeper truth: When someone feels life has passed them by, that their hopes and dreams have vanished, then sometimes entering into fantasy is a way of escaping, of gaining emotional sustenance, when reality is too much to bear. Ollie’s Legz Akimbo days were marked by an almost megalomaniacal sense of self-importance and the divide between his glaring lack of talent and reality were eventually going to snap. That final close-up of Ollie, showing an accumulation of life’s disappointments was a poignant point of closure.

The bingo caller scene involving Toddy, a new character written for the Anniversary Specials, is an achingly moving tragi-comic monologue, the kind that Mark Gatiss has always excelled at in ‘The League of Gentlemen’. As elderly Toddy calls out numbers for a group of bingo patrons he almost unobtrusively begins to reminisce about his life. The numbers help him to recall points in his life, at first touching on small but telling moments before they build to an emotional opening up of his most private, painful memories. The bingo lingo colloquialisms help him explore and express his innermost feelings because they act as a distancing device for him, providing Toddy with the space to confront and deal with them directly. The sometimes ribald parlance of the bingo calling is like a protective layer, allowing him to find a route to his emotions and speak about them. The bingo numbers and patter hold a weight of subtext which resonates with Toddy’s memories as he recollects his life’s journey, its detours and travails: By 26 he’d “never been kissed”, revealing the loneliness, isolation and lack of intimacy in his life; “dirty Gertie. Number 30”, his feelings of guilt over sexual desires; “Legs 11…legs 11”, meeting Cream, a transgender woman in a Thailand bar and falling in love; “Heaven’s Gate. 78”, tragically losing Cream to a hospital caught infection, following a sex change operation.

Toddy’s single scene has the emotional depth of a life laid bare. Mark Gatiss’ outstanding virtuoso acting is done with a touching sensitivity which is extraordinarily affecting. Suffused with feeling, Toddy’s monologue shows there are discreet ways to cradle pain, a world away from the flights of fancy contained in a dream, by expressing deeps wells of emotion through the protective artifice of bingo jargon.

Mike’s request to Geoff to kill Mike’s obese wife gives Geoff the chance to act out the professional soldier fantasy he’s long been attached to, from the time he was in the Territorial Army. As he approaches the Harris’ home at night in order to carry out the ‘mercy killing’ (as Mike terms it) he’s dressed in ridiculous over-the-top army fatigues and camouflaged face. The scene gives Reece Shearsmith’s sublime talent for physical comedy a chance to shine: Ludicrous sideways crab movements, a gingerly executed roll, rapid criss-crossing of his arms in front of his body as if he’s fighting his way through dense foliage and an absurd pole dancer held pose behind a street lamp – it’s a hilariously choreographed and perfectly timed piece of physical comedy business.

Geoff’s attachment to and acting out of his army fantasy life is an idealised substitute for the sense of failure that is his real life and the inadequacies, regrets and unhappiness which make it up. Of course being Geoff he even messes up in his fantasy. He mistakenly goes to the wrong house and ends up murdering Pauline, smothering her with a cushion. That sometimes painful divide between fantasy and reality is brought home with a start when we are shown the aftermath of Pauline’s murder. What had started out as hilariously funny, as Geoff manoeuvred his way with extravagant soldiering stealth to the house, has turned into devastating tragedy.

In a touchingly moving moment, all the more so for being understated, we see Pauline’s broken glasses on the bedroom floor, an imprint of her lipstick on the cushion and a pen on a string (like the one Mickey gave her as a present in series one – “like Swap Shop”) In the end all that remains of a person once they’re dead are the belongings they’ve collected through life and the memories of those left behind. When the camera tilts up to a framed photo on a bedside table it’s of Pauline and Mickey on their wedding day, wordlessly conveying the idea that those memories will be strong and faithfully kept and honoured by the man she loved and who loved her.

The loss of Harvey Denton and the Denton women’s mourning for him – and their once meticulously clean and tidy home – reaches a resolution of sorts in episode two. The grown-up Chloe and Radclyffe eerily resemble Angela Pleasance in ‘From Beyond the Grave’, which effectively primes the viewer to suspect it is their creepy intention to use magic spells to bring their father back, especially as they speak in rhymes, suggestive of the method used to cast them.

Their dream of returning their father to the house involves his resurrection using a toad as the vessel and Benjamin as the unwilling host. Benjamin says “This is madness, madness” as the embalmed body of Uncle Harvey passes into his body (Shearsmith puffs out his cheeks and top lip in a perfection recreation of toad face Denton) Once again the power of fantasy and wish fulfillment – however far into the realms of the extreme and bizarre they are – has exerted itself within the context of a difficult, painful reality.

Lastly, Tubbs and Edward are still secure inside their flat, now with a rapidly developing hostage situation on their hands. Thanks to Tubbs’ confused interaction with modern technology (masterly comic interplay with an iPhone by Steve Pemberton) she mistakenly switched their prisoner Ellie’s pilfered phone to video mode, alerting the media to the fact that the journalist and council worker Lyndsey are being held hostage in the flat. Edward raving that “It’s time we took back control” and “It’s time to become local” conveniently captured on the phone, ramp up the Brexit association – which had been lightly intimated in ‘Return to Royston Vasey’ – to one of Zeitgeist proportions: “…although we’ve never been a satirical show in that sense, there’s lot of stuff in there, “taking back control” which is just inevitably there because it’s in the ether” (2) (Mark Gatiss)

Mayor Bernice readily exploits the hostage situation to bolster her ‘Save Royston Vasey’ campaign by making a connection between the two, inciting the crowds gathering outside the flat. This and a descending media, complicit in the exploitation of the misappropriated narrative, interweaves the underlying Brexit theme even further into the Tubbs and Edward scenes.

Episode two still carried the evocative sense of decline and mortality established in episode one but moved it into an exploration of how people draw on and use narratives by constructing stories or engaging in dreams and fantasies, ones that are better than the real life situations they’re in or the experiences they’re trying to cope with. The passing of time along life’s journey produces a repository of narratives to draw from: Ollie and Geoff derived a form of comfort and diversion with their fantasies; Toddy’s recitation of bingo’s narrative language – its stock phrases and parlance – was the outlet he used to contain his pain. When reality interceded as a counterpoint to these fictions it made the poignancy starker and the characters’ vulnerabilities and humanity even more moving.

Anniversary Specials: 3: Royston Vasey Mon Amour

Episode three is by turns odd, eccentric, weird and nightmarish. It is full of imaginative extravagance that sometimes reaches the level of near madness. It perhaps goes as close to the edge of extreme as ‘The League of Gentlemen’ has ever gone. It is a triumph for the bespoke and authored voice – a distinctive and unique vision. No-one else, except perhaps David Lynch, could even come close to the concepts and imagery unleashed in ‘Royston Vasey Mon Amour’. Where else but in ‘The League of Gentlemen’ would there be moments as daringly odd and disturbing as paper plate face masks by way of Ed Gein, torture by Peri peri olives, a photo booth contraption as sinister as Sweeney Todd’s barber’s chair, a mucus covered toad coughed up by its human host?

There are scenes in episode three which contain behaviour and incidents that come at us from bizarre or surreal angles, which at first may appear difficult to decipher, but they’re driven by an internal logic which makes perfect sense when aligned with and understood through the prism of the creators’ singular universe.

The characters’ story arcs begun in episode one each reach a crescendo. Given the territories they reside in were ones of heightened reality to begin with (by degrees of greater or lesser emphasis) the directional pull towards their fantastical conclusions is both logical and fitting.

Beneath the dysfunctional family history between Pop, Al and Richie, with its mafia allusions transposed to a family-run newsagent business, resided patriarchal control through fear, parental authoritarianism and sadistic bullying and abuse. Al and Richie were left traumatised by their treatment at the hands of their father. It was the reason for Al’s fearful reaction to Pop’s unannounced return and his firm resolve not to tell his father where Richie was now. Through unsettling mind games involving Al’s teenage daughters Pop had forced him to give up Richie’s secret. Pop vowed revenge on his second son for breaking the strict family code of complete subjugation to his demands and wishes.

Richie’s own deli shop is the climatic setting for the story. Threatening torture by Peri peri olives and ‘Picnic’ bars, the terror that Pop induces in Richie has a disturbing subtext – that he carries memories of terrible childhood abuse by his father . When Pop contemptuously dismisses his son as “A fairy who loves fairy stories” it’s a seeded moment redolent with meaning. The Pop, Al, Richie storyline appears to reach an absurdist ending with Pop turning into a genie who is tricked into a glass jar by Al’s wife Tricia, allowing Richie to trap him in there forever. The sequence is then revealed to have been Richie’s wish fulfilment fantasy (a link back to a key thematic of episode two) played out in his head when in reality he’s snapped and stabbed his father to death (“I got you, I got you, I got you, I got you”) The connotations are inescapable: Being able to trap an abusive and terrifying father up in a bottle forever so he can’t hurt or scare him anymore is an abused child’s comforting fantasy, one that a child who read fairy tales (like Richie did) might have imagined. It’s a small child’s fantasy resolution for getting rid of an abuser. Pop’s reference to Richie as being a lover of fairy tales may have been Pop’s usual inventory of verbal abuse against his son but it helped permeate the ending of their story with poignant meaning.

The resolution of Pop, Al and Richie’s tale has eye-catchingly Grand Guignol touches and the re-emergence of the demonic Papa Lazarou in episode three draws similarly demented, macabre ideas and images together, culminating in a nightmarish vision that is, quite literally, a subterranean hell: An underground mine beneath the town from which Lazarou is free to excavate, capture and imprison Royston Vasey’s women at will. With dark irony it is very much Papa Lazarou’s ‘safe space’ (in a grim reversal of the kind that Barbara evangelized about in episode one) as it is protected, secure and hidden away from prying eyes. The secret gateway to this hell is the high street’s photo booth, which has been unceremoniously dumping its female visitors into the dark cavern prison below via the booth’s tipping seat.

With Papa Lazarou’s startling return the two through-plots of the Anniversary Specials – the mysterious photo booth and the threat to Royston Vasey’s existence from the boundary change are connected and merged. It is the Mayor herself, Bernice Woodall, who is both Lazarou’s enabler and the initiator of the boundary change. She agreed to the town’s land being sold for fracking – the reason behind the boundary change – and was forced into signing Royston Vasey’s land over to Papa Lazarou (“He didn’t pay me a penny. I had no choice. He made me”) fracking being an ideal cover for his underground mine.

Using the reality of a current issue – fracking – which is imbued with controversy and anxiety and then putting the weirdest, strangest and Grand Guignolist twists onto it , making no apologies for the bold and bizarre logic of its own unique world is something few creators have the fearless imaginations to convincingly pull off. David Lynch is one that can and The League of Gentlemen most definitely are another.

Papa Lazarou is unique among the League’s characters in having virtually no backstory. He just exists, he is what he is, appearing and reappearing in Royston Vasey almost at will. He is the ultimate inscrutable fiend, informed by our very darkest fears. The third episode summons him up and bestows on him the status of a literal devil, with complete command over his little corner of hell.

‘Royston Vasey Mon Amour’ also pushes internal world oddness to new, mad extremes with the climax to the Denton’s story. The resurrected Harvey is so riven by appalled self-disgust at the thought of being trapped inside Benjamin’s body, convinced it’s a place polluted by onanism and constant self-abuse, that he’s compelled to escape his confinement. This decampment makes Benjamin retch and cough up the toad vessel, resplendent in a coating of mucus. It’s yet another unorthodox high point in an episode bursting with them.

The denouement to the Tubbs and Edward siege storyline pushes the Brexit inferences to the fore more than ever. The editorialising platitudes of tabloid newspapers and the clichéd words parroted by expedient career politicians are mercilessly parodied when a triumphant Edward speaks to the media after a successfully negotiated end to the siege: “Our father raised us to stand up to the schoolyard bully”, “A victory for common sense”, “You can’t make an omelette without breaking a few eggs” are spouted in a perfect recreation of a knee-jerk, one-track mind, conversant only with cliches, rather than informed by knowledge. The whole debased political culture and discourse through which Brexit has been manipulated and propagandised is then ridiculed with a concluding Tattysyrup soundbite that lances it to the hilt: “This is a local town for local people…a local country for local people…and the will of local people will prevail”. It is only when Tubbs and Edward have almost made good their escape that their serial killer tendencies are uncovered, with the discovery of the hostages in a back bedroom, their faces cut off, behind bloodied paper plate masks.

Amid all the Grand Guignol and enveloping strangeness as episode three builds to its conclusion, space is found for a quiet revisit from Les McQueen, now a professional floor polisher. He seems to have made peace with his past and his dreams of recapturing the small glories of his old music career. When he tells Slim, the former ‘Manchester Scene’ music producer, whose floor he’s just polished, that “They do tend to scuff…over time” it is laden with a profound inference. Ostensibly he’s talking about a polished floor but more pertinently he is inwardly referring to his own life and admitting that over time hopes and dreams erode and fade (even though a trace of yearning still remains)

This touching moment of melancholic contemplation (so tonally different from the imaginative extremities and Grand Guingolism pervading most of the finale) is echoed in the beautifully subdued coda of the final scene, which delicately defuses the heightened intensity of the rest of episode three. The emotive, memorable goodbye at the train station, where we see Les McQueen about to go off to Herzlovakia, with renewed hope, his dreams of reviving his music career awakened and Benjamin bidding farewell to Auntie Val and Royston Vasey is a standout TV moment of this or any other year.

Benjamin’s departing words “But you know Auntie Val, sometimes you can’t go back but you can visit” is an achingly poignant, elegiac ending to the Anniversary Specials and frames The League of Gentlemen’s feelings about Royston Vasey – their unique and unforgettable creation – with almost poetic eloquence. Their deep love and affection for it is apparent from the title they gave to the third episode – ‘Royston Vasey Mon Amour’ (Royston Vasey My Love) That last line was full of tender and genuine feeling, both in the words themselves and in the way it was acted by Reece Shearsmith and Mark Gatiss. It came from a place of real, unaffected emotion.

The League made it clear from the moment the Specials were announced, through to the media publicity just before the programmes aired, that their motive for making them was because they wanted to, not because they had to. The line itself “Sometimes you can’t go back but you can visit” defined their approach to the Specials and to the nostalgia that inevitably attached to them. Rather than sentimentally recapture the past preserved in aspic they were clear the revisit was from the viewpoint of the present. Alert to the show’s legacy but aware they had no wish to clone the original meant the three Specials had the Gentlemen’s creative ambition and inventiveness stamped right through it, like a mark of quality assurance. It guaranteed they were special in every possible sense of the word and the best of all tributes to those indelible characters and their world.

It is clear from watching the Anniversary Specials that the League gave a great deal of thought about what they wanted to do with their characters when they revived them to mark the 20th anniversary of their BBC debut.

The Specials celebrate the characters who last inhabited their influential and iconic television series 15 years ago (or 12 years before in ‘The League of Gentlemen’s Apocalypse’ film) The references and influences which infuse the Specials all come from their own ‘The League of Gentlemen’ TV series (1999-2002) “We just, because we were looking back, being influenced by our own show in a way, so we just focused on the characters and what we wanted to do with them” (3) (Steve Pemberton)

Reflecting back on the three episodes and taking them together you can really see how they’re propelled by the character’s stories, how they’re structured towards a series of cliffhangers around each of the character groupings and their developing arcs. You feel involved in what has and is happening to them and compelled to see what will happen next. The episodes are so densely packed, structurally tight and built on stories carrying us forward in the lives of the characters. We are left, for example, longing to know what will happen to Geoff, Mike and Brian now the murder plot involving Mike’s wife has gone tragically awry, how will Mickey cope without Pauline and are Tubbs and Edward ever going to be reunited?

We’re as invested in the characters’ lives as we would be if they were real people that we knew personally because in a sense this is what they’ve become to us. The League of Gentlemen have always been highly skilled at and conscious to humanise and give depth to their characters. With the Specials they specifically thought about them as people with 15 additional years of accumulated life, about how things have changed for them over the passing years. This is what gave episode one such a strong sense of decline and mortality and why episode two underpinned this and allowed time and space for characters to retreat into reveries of fantasy and wish- fulfilment or to confront life’s disappointments and pain through displacement and distancing.

The boldness and daring of the third episode felt at times like being on-board a helter skelter ride as it gathered speed. Ideas and images came at us from all directions as we experienced the characters’ stories draw to a close with an almost sensational intensity, but a tightly controlled one, held in place by the League’s masterly command of their material as the quiet, reflective ending clearly illustrated. “…it was much more about being inside the characters than perhaps thinking about that way we used to think when we were younger…this was much more about telling these characters’ stories” (4) (Jeremy Dyson)

The League’s revisit to Royston Vasey with these three specials was done with an intelligence and undaunted fearlessness that few creators can aspire to, yet alone reach. Their ambition was matched by their commitment to remain true to the characters. This is why 15 years on The League of Gentlemen are still without equal creatively and why the Specials were such an extraordinary artistic achievement.

Footnotes

Writers…Jeremy Dyson, Mark Gatiss, Steve Pemberton, Reece Shearsmith

Director…Steve Bendelack

Producer…Adam Tandy

Executive Producer…Jon Plowman

Associate Producers…The League of Gentlemen

Director of Photography…Mattius Nyberg

Costume Designer…Claire Finlay-Thompson

Music composed by…Joby Talbot and Jeremy Holland Smith

Cast

Anniversary Specials: 1: Return to Royston Vasey

Lyndsey/Val Denton/Mickey/Murray Mint/Brian Morgan/

Iris Krell/Mr Chinnery/Al…….…Mark Gatiss

Mike Harris/Pauline/Tubbs/Herr Wolf Lipp/Ally/

Pop/Barbara (voice only)………..Steve Pemberton

Geoff Tipps/Benjamin Denton/Ross/Henry/Edward/

Bernice Woodall/Pamela Doove (voice only)………Reece Shearsmith

Ellie…Lyndsey Marshal

Receptionist…Gemma Paige North

Daisy…Isla Neild

Mum…Jackie Knowles

Workman…Shaun Mason

Chloe…Francesca Knight

Radclyffe…Lily Knight

Dr Fisher…Andrew Readman

Orderly…Simon Smithies

Little girl…Ruby Longshaw

Mr Webster…Hylton Collins

Tricia…Sian Gibson

Jennifer…Sammy Oliver

Maisy…Claire Cornmell

Radio 4 announcer…Seb Soanes

Anniversary Specials: 2: Save Royston Vasey

Val Denton/Toddy/Lyndsey/Phil Proctor/

Murray Mint/Al………Mark Gatiss

Mike Harris/Tubbs/Dave Parkes/Pop/Harvey Denton……..Steve Pemberton

Geoff Tipps/Edward/Benjamin Denton/Ollie Plimsolls/

Bernice Woodall………..Reece Shearsmith

Carol…Christina Tam

Ellie…Lyndsey Marshal

Tricia…Sian Gibson

Jennifer…Sammy Oliver

Maisy…Claire Cornmell

Billy…Charlie Concannon

Jamilla…Surejya Mckenzie

Carl…Sam Couriel

Chloe…Francesca Knight

Radclyffe…Lily Knight

News producer…Emma Bispham

News reporter…Duncan Watkinson

Eddie…Ellis Todd

Anniversary Specials: 3: Royston Vasey Mon Amour

Val Denton/Lyndsey/Murray Mint/Al/

Les McQueen/Gordon/Gina Beasley……..Mark Gatiss

Pop/Tubbs/Charlie Hull……Steve Pemberton

Edward/Benjamin Denton/Stella Hull/Bernice Woodall/

Papa Lazarou/Slim/Richie………..Reece Shearsmith

Ellie…Lyndsey Marshal

TV Anchor…Tina Daheley

Commentator…Matthew Parris

Luigi…John de Main

Scott…Kris Mochrie

Gareth Chapman…David Morrissey

Swot…Adam Pemberton

Chloe…Francesca Knight

Radclyffe…Lily Knight

Tricia…Sian Gibson

News reporter…Duncan Watkinson

Herzoslovakian woman…Vesna Stanojevic

Advertisements Share this: