TRILOGY OF TERROR

USA, 1975

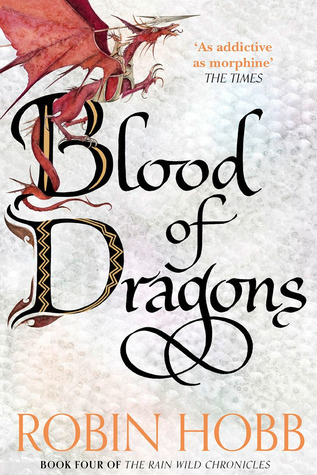

Dan Curtis must have had strong teeth. No one in authority in 70s American television programming would have encouraged him to make The Night Stalker and Trilogy Of Terror. Back then American TV executives were determined to embrace what they thought was the lowest common denominator. These executives claimed to understand the power of what used to be called media networks. Independent minded producers like Dan Curtis survived by gritting their teeth and staying determined. Trilogy Of Terror is a portmanteau movie that collects together three stories by the great Richard Matheson. His vampire and Robinson Crusoe inspired novel I Am Legend is unsurpassed. Amongst his always readable short stories are an exceptional handful, most of which made it into The Twilight Zone. Curtis directed Trilogy Of Terror and produced The Night Stalker. Trilogy Of Terror is not as great as the vampire classic The Night Stalker but it deserves its cult status amongst movie fans.

If Trilogy Of Terror succeeds as a TV movie, the individual stories are not memorable. Most people will anticipate the twists in the first two episodes. The third is less predictable but, because of what has preceded it in Trilogy Of Terror, we soon have an idea of what will happen. The influence of American TV executives is also more pronounced in Trilogy Of Terror than in The Night Stalker. This influence manifests itself as soft focus photography, over-exposed colour film and self-censorship. Oddly, none of this diminishes Trilogy Of Terror. Albeit mainly in passing, Trilogy Of Terror refers ever so politely to rape, Satanism, incest, voyeurism, pornography, diabolic possession, sexual sadism and masochism and, of course, murder. It even has a savage and relentless monster with dreadful teeth although it is only a foot tall.

The title of the first story is changed from The Likeness Of Julie to just Julie. The original title by Matheson is clever. It refers to image and authenticity and the confusion that exists between men and women over identity. But the title of the movie episode is restricted to just the female name. The second story is called Millicent And Therese. In print the title of the third story by Richard Matheson is Prey but in Trilogy Of Terror this becomes Amelia. All three stories in the TV movie have short titles that are nothing more than the names of females. The names alone constitute ambiguity and mystery. In each episode a woman uses fashion and available grooming alternatives to construct a persona. The identities of these women are not just shaped by their emotional needs but by their physical appearance, the influence of other women, circumstance and male expectations and assumptions.

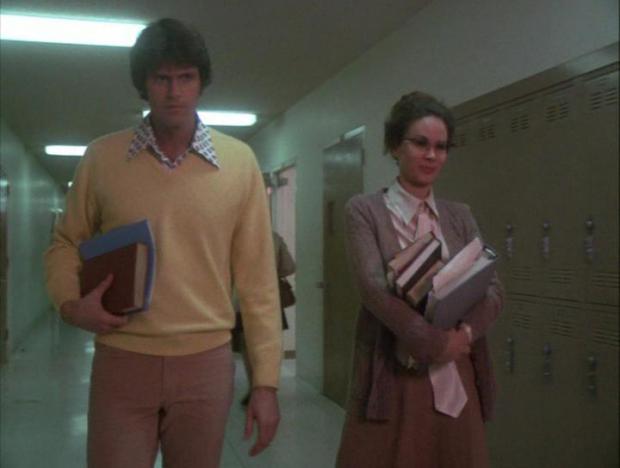

Karen Black appears in all three films. Across the three episodes she changes her character on five occasions. Dress, spectacles and manner are as important as personality. Bright make-up alerts us to the threat of one of the three women, and all are the opposite of what they appear. Karen Black is obliged to be the seductive siren, a female psychopath, a homely spinster, a repressed daughter and an awkward but independent academic. Black was a good choice for the film because she was both attractive and physically flawed. She suffered from strabismus. When she wears glasses, her crossed eyes look confused and suggest an excluded, defeated and repressed spirit. The same eyes, though, when exposed, light a face that has charm. Her voice is also complicated. It varies between being a timid whisper, an irritating whine or a sharp accusatory whip.

Before Trilogy Of Terror the three stories were stand-alone efforts that appeared in print at different times. Dan Curtis was not stupid and he selected them for a reason. He uses the stories to make a feminist point that in a male American TV producer was unusual in 1975. None of the female characters in Trilogy Of Terror have an authentic self. In two of the stories the men are remote and unimportant figures but in the first story we witness a relationship between a man and a woman. The male thinks that by undressing his professor he will discover something sexual, authentic and perhaps primitive. He is doomed because he fails to understand that the deception between men and woman is not just mutual but complicated. The final victory of the woman includes a triumphant burning of the photographs that the deceitful male has taken. She has asserted her own identity, defied the deluded masculine gaze, satisfied some peculiar appetites and overcome the technology that the powerful male assumed would enable him to seduce and control. Written down these events sound impressive and classic Matheson. But the predictable ending of the episode is weak and the narrative is underwritten. The episode feels like it has a missing scene. When Julie says, ‘You see, I’m really bored,’ there has been nothing to explain this boredom.

The second story, Millicent And Therese, concerns a schizophrenic identity. The local doctor who is part GP, psychiatrist and all round good neighbour takes the story towards whimsy and is a weakness in a plot, which already has stretched credibility in an earlier scene with a male lover. The encounter with the child is also unnecessary. Its inclusion is odd considering the excess editing in Julie. The child actor, though, is great. If Millicent And Therese shows sympathy for the female plight and guilt that is a consequence of excessive masculine authority, it also explains male paranoia about women. It may be pleasant for men to have women pander to their expectations and create contrived identities but even men pay a price for these demands being indulged. The continual performance required from women means that men are confused about the authenticity of their own desires.

In the third story a mother dominated woman called Amelia unwraps an exotic purchase from a gift shop. The small statue has powers, and the episode requires her to fight and struggle against a relentless and violent monster. This is both chilling and comic. The episode has at least three surprising and startling moments and it is as terrifying as anything that could be seen on TV screens in that decade. The identity of Amelia is shaped by a desperate need for maternal approval. At the end of the episode Amelia is free of that need but her identity has paid a terrible price. Life for Mother will not be that good, either.

The confusion between the genders that Dan Curtis identified and highlighted 40 years ago still exists. Michael Fallon is, as The Canary editor Kerry Anne Mendoza describes him, a man educated above his intelligence and promoted above his ability. He was also a competent, pragmatic poodle and he had an important part to play in the Conservative Party as all-purpose lapdog. Fallon is no longer the Defence Secretary of the British Government. Like Chad the male character in Julie, our previous Defence Secretary was poor in evaluating the identities of the women he groped. He made the assumption that they would be flattered and excited by the presence of his wrinkled hands on their bodies. Damian Green claims to believe in faith, family and flag. Green is the Minister for the Cabinet Office, or the Deputy to the Prime Minister. Think not to be trusted Alsatian. Colleagues describe this social conservative and alternative terrier as ‘high risk in a taxi’. According to a certain spreadsheet, there are others. In both the main British political parties there have been occasions when the careers and needs of male politicians have been regarded as more important than offences against women. Damage to female employees has been regarded as collateral.

Men and women have seduced and been seduced by one another from when they appeared on the planet but we are still hopeless and helpless. Power, privilege and hierarchy have made a complex mix toxic. Not that the Daily Mail has lost its confident step. No worries in that particular media outlet about the authentic female self in a society constructed by a male hierarchy. Not slow to act it has done a smear job on an offended woman and described her as ‘a very pushy lady’. The message of Trilogy Of Terror was that the authentic self is not available to women. They are expected to be a construction that will help those who own newspapers like the Daily Mail to maintain order. The problem for the proprietors of the Daily Mail is that they are not quite so adept these days at keeping the genders in their supposed place. It may feel like chaos on the streets right now but progress has been made since a headstrong TV film producer challenged accepted notions of how men and women saw each other and themselves. Today there is not just Dan Curtis who has noticed something odd. Actresses complain of sexual exploitation, and political party activists feel less obliged to indulge men who have either been educated above their intelligence or promoted above their ability. Meanwhile the Daily Mail sells fewer copies.

Howard Jackson has had six books published by Red Rattle Books including novels, short stories and Horror Pickers, a collection of film criticism. If you are interested in original horror and crime fiction and want information about the books of Howard Jackson and the other great titles at Red Rattle Books, click here.

Advertisements Rate this:Share this: