(For the previous “Best Hitchcock Movies” list click here.)

The problem with creating a “Best Hitchcock Movies” list is that so many of the picks are plainly obvious. Any list that does not include Vertigo, Psycho, North by Northwest, Rear Window, and arguably The Birds in the top 10 is automatically illegitimate in my book. In addition you’d have to make a strong argument for why Notorious, Strangers on a Train, or Shadow of a Doubt doesn’t make that list either (and no, I did not have a strong argument for any of those). So if you’re keeping count, that’s 8 out of the top 10 slots pretty much sewn up from the get-go.

Really then, it’s only in the next ten movies that things get really interesting. It’s testament to just how much depth of quality there is to Hitchcock’s career that there were still too many candidates to fill the “next best” Hitchcock movies. While they may not reach the impossible heights of the very best Hitchcock movies, there is no doubting that these next ten are still very good movies, made from great stories and featuring great performances. Many of them find Hitchcock venturing into new genres, experimenting with different techniques, and finding unique ways to tell stories. Some of these movies are unquestioningly great.

Contrary to other lists, I’m not going to rank these movies simply because after the top 10, it becomes an exercise in splitting hairs to determine which movie ranks where. Instead we’ll just use good old alphabetical order for this list.

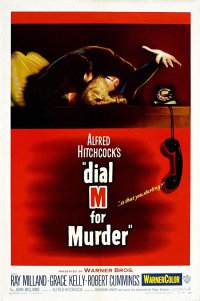

DIAL M FOR MURDER (1954)

This movie is remarkable simply for the fact that it was filmed in 3-D, a half-century before it ever became a standard feature in multiplexes everywhere. Due to this use of technology it is also one of Hitchock’s most intimate films as it is almost entirely shot in the confines of one apartment. The plot is typically Hitchcockian: Professional tennis player Tony (Ray Milland) discovers that his wife Margot (Grace Kelly) is having an affair and conspires to have her killed as a result. When the plan goes awry and the would-be killer is killed instead, Tony quickly pivots to pin the blame on his wife which starts a dangerous cat-and-mouse chase as the investigators circle close to the truth and Tony uses all his wits to keep them away from it. Besides being a classic Hitchcock tale of salacious murder, the chamber play nature of the movie also gives us the perfect opportunity to study and appreciate how Hitchcock blocks a scene, and by so doing affording us an opportunity to appreciate his genius more.

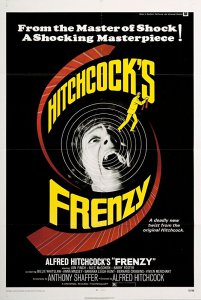

FRENZY (1972)

Hitchcock’s later career failed to reach the impossible highs of his output from the 1940s till the early 1960s. Coming off the back of two less-than-successful spy thrillers, Hitchcock returned to the well of murder that had brought him his greatest success in Psycho. Here he trades in the Southwest of America for the fog-ridden streets of modern London where a serial-killer is raping women and strangling them with neckties. Though we know very early on who the killer is, the police have a suspect who fits the stereotype much better. And in typical Hitchcock fashion, the tension and pleasure of this film is seeing whether the right person will be caught and if the innocent will actually be exonerated. Freed from the confines of the Production Code, this is also famously the only Hitchcock movie to have any sort of nudity or grisly violence. Take away those admittedly distracting elements though, and this is a perfect return to form from the master of suspense that slots in perfectly with the very best of his heyday.

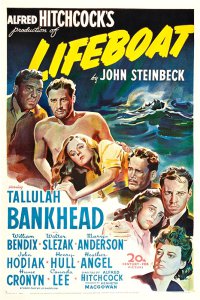

LIFEBOAT (1944)

Much like Dial M for Murder, Rope, and Rear Window this movie belongs in the unique sub-genre of Hitchcock films that use a limited setting. And much like those previously mentioned films, the self-imposed limitations of Lifeboat’s setting created some of the best dramas of his career. In Lifeboat, a diverse cross-section of 1940s society find themselves on a lifeboat when their ship is sunk by a U-Boat in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Including people of different religions, races, classes, and nationalities (including the controversial sympathetic depiction of the German U-Boat captain who similarly finds himself trapped on this lifeboat) the movie quickly becomes a petri dish of conflict as prejudices are quickly forced out into the open and the quest of survival brings the best and worst out in the individuals on board. Although none of the characters in themselves are deep enough to warrant their own movie, together they create a compelling and underrated drama that reflects the anxieties and fears of a world in war.

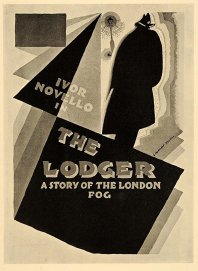

THE LODGER: A STORY OF LONDON IN FOG (1927)

Hitchcock would be the first to say that his silent films are generally speaking not the best of his career as he openly views that period as his “amateur phase” when he was learning the tricks of the craft that he would later perfect. But with respect to Hitchcock, I would argue that his third feature The Lodger is worth a look for more than just the academic purposes of seeing his early career. The story is basically a riff on Jack the Ripper as an unknown murderer calling himself The Avenger keeps killing young blonde women on the London streets. While being the genesis of many of Hitchcock’s obsessions with macabre material, it is also easily his most atmospheric as he bathes the streets of London in a typically eerie light. In Ivor Novello as the mysterious lodger of a boarding house we also have perhaps the earliest instance of Hitchcock’s wronged man, although there has never been a more creepy or insidious character to ever occupy that role. And despite this creepiness Hitchcock still manages to infuse this story with pathos as the truth about the lodger starts to come out. Without the burden of dialogue, The Lodger easily is one of Hitchcock’s most impressionistic and evocative movies and a rival to any of the other great movies of the silent era.

THE MAN WHO KNEW TOO MUCH (1956)

Now I know that many people are going to argue that this remake is a pale comparison to Hitchcock’s 1934 original starring Peter Lorre and to be honest, they do have a strong case. But I find the 1956 version of The Man Who Knew Too Much superior for a few reasons. First it has Jimmy Stewart, and there has hardly been a movie that isn’t made instantly better with his presence in it. Along with his co-star Doris Day, they create what is perhaps the most realistic depiction of a couple and a family in all of Alfred Hitchcock’s films (admittedly a depiction of any family is rare enough). Additionally, their stumbling upon a plot of espionage and assassination takes on much more weight because they depict such a believable domesticated family. While Hitchcock made a career out of people being caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, The Man Who Knew Too Much feels like the first movie where the characters behave in the same clumsy way an ordinary person might in those circumstances. But the final reason the remake pips the original, is that this movie has special place in my heart because it is the first Hitchcock movie I ever saw way back in a college course on film. So there you go.

REBECCA (1940)

It is tragic that Alfred Hitchcock never won a Best Director Oscar and only ever won one Oscar for Best Picture. It is also ridiculous proof that the Oscars have always been a generally poor judge on quality that the only Hitchcock movie to win Best Picture was Rebecca. Not that Rebecca is a bad picture mind you. This adaptation of Daphne du Maurier’s novel is a perfect example of a classic Hollywood melodrama, with great performances from Joan Fontaine as the second Mrs. de Winter who marries into a wealthy family and finds herself in bitter competition with the memory of the deceased Rebecca who was the first wife of Maxim de Winter. Featuring a hall-of-fame movie mansion, a diabolical villain in the head servant Mrs. Danvers, and a tragic and haunting conclusion, the movie has a lot going for it that is great. Ultimately though it just doesn’t feel like a Hitchcock movie and pales in comparison to his greatest works.

ROPE (1948)

Rope is extremely close to an experiment that succeeds superflously. The conceit of shooting a movie without any visible cuts is an achievement in our digital age when seamless cuts can be made instantly and cleanly. But to do that in an age of physical film, where cuts were made manually, and where a camera could only film about 10 minutes of film at a time is absolutely audacious. And for the most part the movie works. Hitchcock keeps us confined to the apartment of an upper-class couple while they host a party in honour of their murdered friend whose body they have hidden in plain sight. By never visibly breaking the cut, it simply adds to the tension as the camera is never more than a few feet from the hidden body as each guest comes perilously close to uncovering the whole plot. Unfortunately though, by making the film a continuous shot, the movie loses some of its urgency as some key scenes have to be shot from a less-than-ideal distance and others move around in a clunky way. Still, the movie just about works and is a clear example of the the willingness to experiment and take risks that made Hitchcock great.

SABOTAGE (1936)

Famously this is the movie that made Hitchcock say many years later about his “bomb-under-the-table” theory of suspense, “The bomb must never go off.” This pre-World War II story about an underground terrorist group that seeks to disrupt and dishearten the city of London is a fascinating document about the fears and anxieties of a nation as the spectre of war begins to rear its ugly head. The movie focuses on Mrs. Verloc (Sylvia Sidney) who unbeknownst to her is married to one of the members of this terrorist group. She comes in contact with undercover investigator Ted Spencer (John Loder) who begins to suspect her husband and in typical Hitchcockian fashion most of the drama comes in the cat-and-mouse game that Spencer plays with Mr. Verloc (Oscar Hamalka) and whether or not Mrs. Verloc herself will come out unscathed. But because this is the movie where the bomb does literally go off, it is also perhaps Hitchcock’s most tragic film and given the rarity of real tragedy in Hitchcock’s work is an interesting entry into his career.

TO CATCH A THIEF (1955)

Breezy romantic flick is not the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the name Alfred Hitchcock yet that was exactly what he achieved with To Catch a Thief. It stars the suave Cary Grant as the retired cat burglar John Robie who is looking to clear his name after a series of break-ins that match his modus operandi start occurring. And joining him is the effervescent Grace Kelly as Frances, the daughter of one of the richest people in the picturesque French Riviera where it is located. Drawn to each other by the lure of romance and adventure, the two set off on this quest to catch the copycat burglar. And in typical glamorized Hollywood fashion, this quest leads them to balls where they naturally have to dress to the occasion, exotic locations that are postcard-perfect backdrops, daring night-time heists that feature close calls and tension aplenty, and the aforementioned promise of romance between the two leads. But of course in typical Hitchcockian fashion, it is not merely that either, with the master proving he does have one or two tricks up his sleeve.

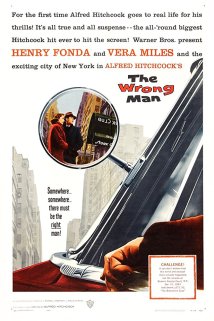

THE WRONG MAN (1956)

While the title of the movie could accurately sum up a gigantic chunk of Hitchcock’s movies The Wrong Man represents a departure from the director as it is the only movie he’s ever done that’s based on a real story. As such the story about Manny Ballestero (Henry Fonda) being wrongly convicted for a crime takes on a more somber tone than the rest of Hitchcock’s work. But if the movie’s attention to the details of this true-life story lacks the typical levity that’s so often associated with his work, he more than makes up for it with his style and craft. The movie is frequently heart-wrenching and vivid with Fonda in particular turning in a typical star-making performance as the wronged Manny. The scene in which he is met by his demons while in prison is easily worth the price of admission alone. The movie is a testament to the fact that while Hitchcock did have a distinctive style that worked particularly well in a specific genre, he was by no means confined and could easily adapt to the more “serious” genres of drama.

(Author’s Note: With my second child due to arrive this week, I’ll be taking a two week hiatus. Thanks to all of you for taking the time to stop and read my musings on movies. I’ll be back soon enough!)

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave

SaveSave

Share this: