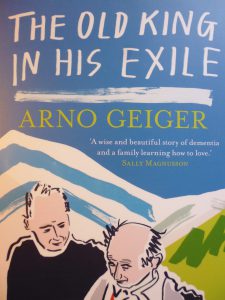

This moving and insightful book  relates the slow decline of the author’s father over several years as he suffers from dementia. The beauty of the narrative lies in the way the author roots his father so firmly in the Austrian village of Wolfurt that we feel his deep connection to this place and then his sense of exile when he no longer recognises his home. At the same time Arno Geiger ranges over his father’s upbringing and family life in this rural setting, as well as his own childhood and early life, giving us a sense both of continuity and of change over generations.

relates the slow decline of the author’s father over several years as he suffers from dementia. The beauty of the narrative lies in the way the author roots his father so firmly in the Austrian village of Wolfurt that we feel his deep connection to this place and then his sense of exile when he no longer recognises his home. At the same time Arno Geiger ranges over his father’s upbringing and family life in this rural setting, as well as his own childhood and early life, giving us a sense both of continuity and of change over generations.

The book begins when his father, August, is in the intermediate stage of dementia: the illness has been diagnosed and August is needing regular care and support. He needs help with practical tasks like getting up, getting dressed and his language is random, at times engaging in dialogue with his carers which makes sense, but then sliding off into his own reality. By night, he wanders like a king in exile, and is frightened by things swaying, by their instability. His son, Arno looks back to the onset of the disease, regretting bitterly that the family didn’t recognise sooner what was happening to their father. Recently retired and his marriage of 30 years having ended, August took to watching TV and playing patience. Previously a physically active man, constantly engaged in house improvement projects, this seemed a change of character. The family put it down to him ‘letting himself go’, rather than August withdrawing from the world, aware that he was losing competency.

Arno describes the diagnosis as something of a relief: the family know now what they are dealing with and set up systems of care with family, neighbours and, eventually professional carers. Arno’s own relationship with his father changes. He spends chunks of time in the family home, sharing care of his father with others, but writing too- Arno Geiger became an established writer during the years of his father’s decline. The two men live around one another during these periods, chatting, being silent together, walking together a little and there are moments of touching companionship described. Arno talks of the importance of going over the bridge into the world of the demented person, of not contradicting them by insisting on the truth of any objectively verifiable reality. This kind of insistence only makes the sufferer feel even less secure, worries and distresses them and serves no purpose.

These vignettes of their companionship are interleaved with observations about his father’s past. August Geiger was born in 1926 into a poor rural family in Wolfurt, Austria. He was brought up during the Nazi period and was conscripted in 1944. Taken prisoner by the Russians, he contracted dysentery and spent 4 weeks in a military hospital,weighing just 6 stones when he was released. After his father returned to Wolfurt, he never wanted to leave the village again- which provoked terrible rows with Arno’s mother, an outgoing woman who craved a bit of excitement and adventure. This was just one point of contention in their marriage which was tolerable enough while busy with small children, but then after some years an ‘ugly atmosphere‘ developed and Arno describes an unhappy home where all family members went their own separate ways. And this was against a background of post war buttoned-upness: August’s brother Paul says the ‘social landscape after the war was as bleak as the moon’s surface: piety, conservatism, a sense of decency and nothing but work’. Given these circumstances, August Geiger had difficulties relating to his children from adolescence-as did many fathers of that era- and Arno very much went his own way. Which makes the account of the warmth of their relationship when August’s mind, memories and personality are ravaged by Alzheimer’s, all the more poignant.

The degenerative nature of Alzheimer’s means that carers are regularly presented with new challenges. As the disease progresses, August no longer recognises his own home and is restlessly, constantly searching for it, while his spatial orientation is deteriorating. Objects go missing and others are blamed. His take on reality becomes disturbing for the family when they realise he thinks the TV presenter is in the room and goes up to the TV screen to offer him a biscuit. The situation is becoming increasingly frightening for August too: he has hallucinations and reacts aggressively to a new carer who doesn’t know how to handle him. The demands are such that the family decide he will have to go into a home: the up side is that a place becomes available in the residential home in the village which he knows and where they know him and his transfer there goes smoothly.

Though Arno’s brother and sister can’t bear the home, Arno himself has no problems with it and continues to visit his father there. In recognition that August is now in the final stages of his life the family clear the house out and come across objects which evoke memories of a bygone era : ‘an old coffee mill, a wooden schnitzel mallet, lampshades, the drum from my parents’ first washing machine‘. More telling are the notes Arno finds which his father wrote as a 24 year old about his war experiences. Arno knew as a child that the period spent in the Russian military hospital with dysentery had marked him : in his wallet he always carried a photo of himself, 6 stone, emaciated, on his release from hospital. However it is only when reading the notes found in the cellar that Arno finds out the terrible things his 18 year old father saw in that hospital and realises the extent of his trauma.

In the last section of the book, the paragraphs are shorter and less connected, snatches of dialogue between the two men, observations of life in the home, statements and aphorisms, as if reflecting the intermittent and unconnected nature of expression and communication in the later stages of Alzheimer’s. As if the mind, like a flame, flickers into life for a moment and then dies down. I read this book in German when it was first published- it helped me understand my own mother’s gradual decline into dementia. I clung onto the portrayal of August Geiger as I had clung on to moments when my own mother’s personality shone out and she was still herself. Reading it again now in Stefan Tobler’s excellent translation I am reminded of the importance of this kind of memoir for all of us when Alzheimer’s touches our lives more and more. To help us recognise the beginnings of the disease and find ways of living with it, whether carer or sufferer, while keeping the person still there, still alive.

Arno Geiger has recently been in the UK discussing his book. You can hear him talking about the book on BBC 4 Midweek and in this short Youtube video .

Advertisements Share this: