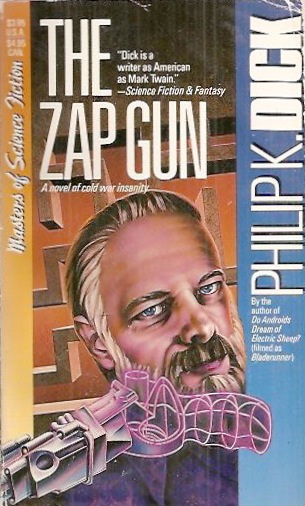

The Philip K. Dick series continues.

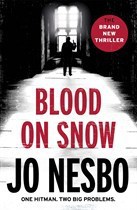

Raw Feed (1989): The Zap Gun, Philip K. Dick, 1965.

In a certain sense, Dick’s negative assessment of the novel’s first half being utterly unreadable is correct.

The opening is boring and confusing. We never do get a coherent explanation of “plowsharing”: it seems to be conversion of mass produced weapons’ components — which seem to work — into civilian consumer goods hence giving the illusion of security and providing an economic boost and salvation from the cost of the arms race.

Like The Penultimate Truth, this is a fake Cold War perpetrated by the power elite of East and West for their benefit. (But it is unclear exactly what the populace believe to be true).

Here the weapons are not those horrifying weapons of mass destruction of old (which are sadly lacking the Sirian slavers show) (a truly moving moment is Lars Powderdry’s reaction of the horror of a mere pistol) but rather silly, if inventive, weapons like the Garbage Can Banger that keeps the enemy wake, produces obnoxious odors, or merely mess up his bureaucratic records. That is a funny element. And Lars Powderdry’s horrified reaction to a mere pistol is truly moving.

Those old, truly destructive weapons of old are shown to be sadly lacking by the Sirian slavers.

I thought Surley G. Febbs was totally unnecessary to the plot but occasionally funny in his arrogance.

I thought the novel really only took off when Dick began to pile on the baroque, van Vogtian plot twists starting with the revelation that Powderdry and Lilo Topchev are not tapping into a mystical dimension with their trances but the mind of an obscure comic book artist. (Dick’s works of the period often seem to feature creative people in rather despised jobs). The book got really fun then.

The toy designed to psychologically corrupt the enemy (here with “empathy”, a good thing) is much like Dick’s “War Game” and a touch I liked along with that of the uncurious Sirians.

I found the relationship between Powderdry and Topchev (as many of the relationships between man and women in Dick’s works) strange, troubling, and realistic.

While not as disturbing and memorable as Norbert Steiner’s suicide in Martian Time-Slip, Maren Faine’s suicide was moving.

There are plenty of usual Dick touches: authoritarian states, private police forces (like the Foote men in The Penultimate Truth), troubled relationships, peculiar plot twists, and humor. Appearances are questioned, fakes proposed, fakes debunked, and fakes affirmed. Dick called it his null-null Y plots after critic Patricia S. Warrick’s observation.

“Afterword”, Maxim Jakubowski — A rather perfunctory examination of the novel with by now familiar details of Dick’s life (or, at least, Dick’s familiar accounts of his life). I disagree with the rather silly insinuation here (and elsewhere amongst “literary” minded sf critics) expressed that somehow Dick’s sf novels weren’t really sf because they dealt with his personal obsessions and relationships and contemporary political situations. Sf is a style, a genre, an “invitation to form”. Sf is the surface trappings, the robots, slime molds, alien slavers and rationalized fantasy and beneath the surface sf can deal with any issue or theme the writer wishes it too.

More reviews of fantastic fiction are indexed by title and author/editor.

Advertisements Share this: