“WAITRESS” IS WELL SERVED AT THE ORPHEUM

Inevitably someone is going to call Waitress, the Musical a slice of life, given that pies seem to be a major part of the show. Yep, the subject of such desert is a theme, but consider it more colorfully decorative than significant. The serious parts of the show have more substance.

The national traveling company version of the current Broadway hit has much to recommend it: an intelligent script with some solid dialogue and good funny lines by Jessie Nelson derived from Adrienne Shelly’s 2007 screenplay, perceptive direction of serious elements by Diane Paulus and agreeable, friendly, sometimes C & W-like songs by Sara Bareilles. This all-woman team has everything served up by a polished cast with good voices and genuine acting talent.

A lot of charm pervades the show’s first act, mixed in with a story of acceptable substance. However, the second act seems to be looking too hard and overlong for something interesting and amusing until working up to a resolution of the serious parts of the story. FYI: Pies are often prepared and discussed. They sound tasty. There are also real ones (cherry), sold in small jars in the lobby pre-show and at intermission.

Jenna works at Joe’s Pie Diner and is close pals with sassy, earthy Becky and frenetically anxious Dawn. Jenna is pregnant by nasty husband Earl and doesn’t want the baby. Going for a checkup, she connects with married new-in-town OB/GYN Dr. Jim Pomatter. The connections intensify. Meanwhile Joe tells Jenna about a prize-winning pie competition in a nearby town urging her participation. Dawn develops a relationship with wacky blind date Ogie, an ongoing comic element of the story. While Jenna’s ties to Earl and Jim are severely stressed, eventually she finds her bearings, coming to love baby daughter Lulu.

Nelson’s script excellently makes Jim a very special guy and gives Earl enough dimension to seem real. Jim’s sweet innocence offers a good contrast to Earl’s darkness. Nelson has written enough good dialogue to make the story feel genuine, enriched with often amusing dialogue by Joe. Note, however, that in portraying two extra-marital relationships, this story may not be for impressionable kids, as well as a fast-paced choreographed depiction of Jenna and Jim getting it on together.

Paulus has the serious elements well played and paced. On the other hand, when it gets to the comic stuff, the playing gets cartoonish, especially with too-obvious Dawn. Yet Dawn’s outsized qualities find their match in Jeremy Morse’s Ogie whose star turn in the first act stays so full of fun and charm that it feels inevitable that audiences would cheer as he leaps off the stage.

Bareilles’ rarely rhyming lyrics sound interesting and original but the music in most of her songs doesn’t have equal personality. Although a catchy kitchen utensil percussion piece matches up well with the cast’s always energetic singing. Sometimes a good beat also gets going, played by a solid six-piece on-stage band.

Bryan Fenkart’s wonderful timing makes Jim’s early awkwardness both funny and special, a character full of personality. As Ogie, Jeremy Morse delightfully continues in the role he played on Broadway. His amazing, dynamic and goofy playing in the first act owns the stage. And Larry Marshall’s Joe always remains lovable; he plays the part with relaxed, never forced appeal.

Add to them two local little girls, Vienna Maas and Anina Grace Frey alternating as Lulu in what’s bound to warm your heart.

The scene designs by Scott Pask tell the story well. Jenna and Earl’s depressingly dark home makes a valid statement while, elsewhere, the wide-open spaces certainly challenge people living there to find ways to make their lives meaningful.

Yet, suddenly, in the last part of the second act, Jenna’s ultimate triumph surfaces so swiftly with such sparse development that it resembles a movie on TV with scenes missing because the show was edited to run in the time allotted. The show deserves better. But who’s going fix that now? It’s doing well on Broadway. In any case, the good qualities certainly make for a lot to admire.

Waitress: The Musical is served up through December 17th at Slosburg Hall, Orpheum Theater, 409 S. 16th Street. Fri.: 8 p.m. Sat.: 2 & 8 p.m. Sun.: 1:30 & 7 p.m. Tickets $59- $133. https://www.omahaperformingarts.org/

” Spring Awakening” Stirs the Heart

Spring Awakening pulses with truth and vitality at UNO Theatre. The pointed story of this musical comes across as a living thing. The performers’ singing and acting glow with personality and soul, enriched by co-directors Doran Schmidt and Wai Yim’s perceptive and inventive colorations. Appropriate to the story, this ensemble feels like people who have known each other for years.

Clearly they have material whose own merit has much to offer, especially Duncan Sheik’s music, (duncansheik.com/) memorably bringing out fine choral harmonies and solos, duos, trios where vulnerable tenderness belongs, or when urgency throbs in rock music kinship with the youth of today. Hear how Schmidt as music director points that up with stomping feet. When the rock songs sound, the staging carries extra-musical dimensions, like contemporary rock acts. Of course, legitimately implying ageless youthful rebellion against social restraints.

Choreographer Wai Yim fills the space with movement, using the large area to have young people ebb and flow, trying to find themselves, while dominating adults tellingly hover above them. The cast inhabits these lives in multiple ways, bodies sometimes saying what words may not.

Lyricist Steven Sater (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steven_Sater) wrote the script based on a play by German author Frank Wedekind about life in an adult-dominated, repressive culture of a small German town in the 1890s. There, young people are starting to burst at the seams which confine them to childhood. They urgently want to grow, their bodies metamorphosing, but not knowing why or how to do what hearts and minds urge. Hence the awakening at the season of re-birth. Sater’s excellent, inventive lyrics also urge the story on.

The main thrust becomes ultimately tragic in Wedekind’s criticism of such a society, showing how it damages youth, inserting intelligent questioning of religion and of accepted ideas through one character, Melchior Gabor. While those points are made, they are primarily elements underlying the story rather than the focus.

Certainly dealing with and/or showing masturbation, teen sex, violence, sadism, parental sexual abuse, homosexuality, suicide and abortion, it’s clear why the play was initially banned and an adult language-sexual theme alert is printed on the program for the musical version.

Yim perceptively has stylized interactions across the generations, showing them unable to connect. Or having the body of Moritz, after his suicide, buried as a skinny mike stand, as if to say his voice is forever silenced. Yim and Schmidt also have songs delivered with performers holding prop hand mics implying electronic connections from this German past to today. And they’ve chosen to find fun in having Mike Burns’ Hänschen beat off to the rhythm of the band behind him.

Costume designer Valerie St. Pierre Smith also makes a telling point with Bethany Bresnahan’s Ilse trying to seduce Moritz, her skirt hiked up above a thigh. And the scenic design by Steven L. Williams convincingly, darkly looms over the young people, saying that the place where they live imposes its darkness. Also note his remarkably inventive grave stones.

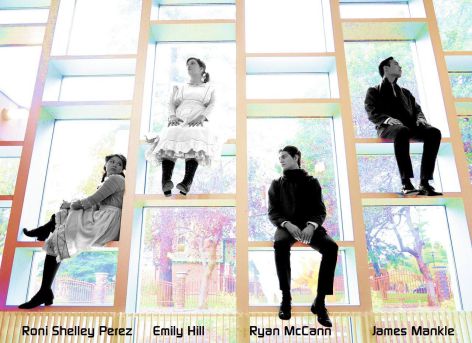

Amid the performers in this impeccable cast, Ryan McCann, Roni Shelley Perez (above photo), Nick Jansen and Simon Lovell stand out in the most significant roles. McCann convincingly gets across Melchior’s transition from young boyhood to burgeoning maturity. As Wendla, Perez sings with a beautiful, touching voice. Jansen’s version of Moritz’s sad and confused vulnerability stays completely convincing. And Lovell, with versatile truth, makes the most and best of a variety of adults.

Note also a page in the program book. It provides links to suicide prevention support, touching on a theme within the script, which might be very close to home. Further, a post-performance appeal asks for another kind of support, donations to Planned Parenthood, a reminder about the vicissitudes of having children.

Given all this talent, you may want to hold and cherish these young people, as performers and as characters, hoping they will find their way to brighter futures.

Spring Awakening is performed at 7:30 p.m. Wednesday and Thursday November 29th and 30th , Friday and Saturday December 1st and 2nd. At Weber Fine Arts Building, UNO. 6001 Dodge Street. Tickets are $5- $16, free for UNO students. www.unomaha.edu/unotheatre

Teens Are Rocked Back and Forth, yet they can sing.

Rock music pulses in a musical about teens whose pulses race with hormones. It should. Yet, in the now-famed 2006 Broadway production of Frank Wedekind-based Spring Awakening, the time and place are not here and now but in his late 19th Century homeland: Germany. And in the young people’s homes, families and schools there is no understanding, no sympathy about young people’s confusion about sex. Their deeply stressed lives unfold at UNO Theatre.

Wendla and Melchior are growing up in a tightly-wound small community. Her body gives her messages she can’t fully understand, and which her mother won’t explain or comfort. Young Melchior knows what ails Wendla. Soon, offering her solace and understanding, he and she explore their bodies. Meanwhile Moritz struggles with the deep pain of his urges while Ernst and another boy, Hänschen, yearn for each other. All this and more for other kids continue amid physical abuse, cruel and deceiving teachers, harsh parents and the tyranny of their society’s belief in its own righteousness.

Wedekind published his play more than 115 years ago, trying to show the ugliness of that society, in pity bringing to the fore the agonies of the youth of his day and its struggles in dealing with natural urges. As if to say that this is the truth, deal with it. Before this musical became so famed, he was best known for a two-play series —Erdgeist (Earth Spirit, 1895) and Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1904). Poking at the gross underbelly of smug prosperity, he pushed the boundaries of what was acceptable on stages in those days.

Duncan Sheik, a successful rock singer and songwriter, wrote the score for this musical when he was in his late 30s after having written another original one in 2002 for the New York Shakespeare Festival. Lyricist Steven Sater had already been collaborating with Sheik before they got together on this 2006 off-Broadway project. Sater is also co-creator and executive producer, with Paul Reiser for both NBC and FX, Sater also developing projects for HBO and Showtime.

This show moved to Broadway that same year and ran for three more. It garnered eight Tonys including those for Best Musical, Book and Score. Plus four Drama Desk Awards, while the original cast album received a Grammy. New productions have emerged world-wide ever since. That makes sense; the story that it tells about the pains of bewildered youth resonates everywhere.

“A fresh breeze of true inspiration blows steadily (with its) alluringly melancholy music,” said The New York Times. “It is also exhilarating and the arching sense of adventure makes an unforgettable statement.”

Clearly UNO students belong in these youthful roles; there are 10 of them in this cast of 13. There’s a two-keyboard, guitar, drums, bass combo playing the music, Doran Schmidt leading from one of the keyboards. He’s directing as well, along with choreographer Wai Yim.

As these young Germans awaken, hope springs eternal that they can live their dreams and escape their nightmares.

Spring Awakening is performed at 7:30 p.m. Thursday to Saturday, November 15th to 18th, Wednesday and Thursday, November 29th and 30th , Friday and Saturday, December 1st and 2nd. At Weber Fine Arts Building, UNO. 6001 Dodge Street. Tickets are $5- $16, free for UNO students. www.unomaha.edu/unotheatre

A CLASS ACT

Bluebarn Theatre has a remarkable spectacle going. It’s Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, The Musical, a 2006 recycling by Australia’s Allan Scott and Scotland’s Stephan Elliott of a 1994 film which Elliott wrote and directed.

Re-cycling is a major word here. Because the wonderful sets and costumes are deliberate choices of such elements as multi-colored plastic bags, gleaming empty plastic water bottles and so much more. Their look and feel enhance but never dominate an energetic and wonderful cast which sings and dances as if there were no tomorrow.

Indeed, the musical elements clearly become the focus for which the story serves as a vehicle, more so here than in the movie. The essence focuses on three drag queens, Tick, aging Bernadette and young Adam who take their act on the road in a bus named Priscilla. Tick organizes that trip because his estranged wife has asked him to stage performances at her club in the remote, desert-surrounded central Australia city of Alice Springs. She also wants him to bond with his young son. There are a few encounters along the way with hostile and with somewhat friendly people. An elderly auto mechanic named Bob, a long-time admirer of such acts, eventually goes along for the ride.

The story does not get taken too literally. No surprise, given that the core concerns three men personifying women. Or that a bus on stage is a central element. Moreover, the parade of costumes certainly exceeds the capacity of the bus and any luggage therein. And, as if bopping into fantasy, a vibrant vocal trio materializes regularly en route, fronted by compelling Miss Understanding, a show herself.

Despite some funny lines, a few of them bitchy, and intentionally far out costumes, co-directors Susan Clement-Toberer and Randall T. Stevens and their cast take the story-line seriously. You could read into it something about accepting LGBT diversity, but that doesn’t seem to be in the foreground.

This is most definitely a jukebox musical given that many songs from the late 60s, the 70s and early 80s became famed pop hits. More recycling. Some seem to fit the premise well. And, given the throbbing beat of many, they clearly call for flashy moves. Credit choreographer Melanie Walters for making the most and best of them.

The stage stays constantly alive vocally and visually with solo numbers, duets and ensembles doing their thing without unerring polish and verve. Matt Bailey as Adam has a beautiful voice, and Roderick Cotton’s Miss Understanding stays astonishing from start to finish.

As for the acting, Cork Ramer stands out as Bernadette with elegant poise and memorable, sweet dignity. And Mark Hinrichs’ Tick and Don Keelan-White’s Bob have genuine believable substance. However, opening night, Matt Bailey, playing Adam, seemed to be going overboard

Although the movie had many of the same songs, famed recordings of them were on the sound track and openly lip synched, consistent with the idea that this drag road show was not a high budget affair and had camp elements …no pun intended. In this stage production, nearly everything is sung live.

On the other hand, the constant use of deliberately low budget materials for curtains, sets and props by imaginative Martin Scott Marchitto, along with equally amusing and goofy costumes by Jennifer Poole, certainly fit the idea that the traveling trio might have to use whatever’s on hand. The bus, by the way, when first wheeled on stage, got a round of vigorous applause that evening. Deservedly.

The Broadway version of this show has become a legend, having run for 15 months there and now constantly produced world-wide.

Other Elliott films include Easy Virtue and A Few Best Men. Scott’s include Regeneration, The Awakening, Don’t Look Now, Castaway and The Preacher’s Wife.

A trip!

Priscilla, Queen of the Desert The Musical runs through June 25th at Bluebarn Theatre, 1106 South 10th St. Thurs.-Sat.: 7:30 p.m., Sun. June 4, 11,18,25: 6 p.m. Tickets: $25-$30. http://www.bluebarn.org

Fresh and Memorable

Sweetness and something substantial to chew on enriches the space at The Playhouse in Tracey Letts’ charming and engrossing Superior Donuts. Indelible writing, performing and directing make this one of the highlights of this season. It lives.

The minute the action starts, you could become immediately engaged as Mark Thornburg makes the stage vibrate with vitality as Max Tarasov. That ex-pat Russian owns a DVD store next to Arthur Przybyszewski’s casually minimal, time-warp, just-vandalized donut shop in a nearly- transitioning Chicago neighborhood. Randy and James, two police officers, made thoroughly real by Julie Fitzgerald Ryan and Devel Crisp, inspect and investigate.

Then Arthur arrives and seems unmoved by the destruction. Not surprising. His life has long been a shambles itself. Watch how Keven Barrett makes this man sigh and breathe with endearing solemnity.

You’re hooked. And if you aren’t yet, wait until Aaron Winston as Franco Wicks pops onto the stage. He owns the territory as the 21 year black kid who applies for an assistant Arthur needs. Franco/Aaron is so full of energy, goodness and lovability, that you’re bound to believe that Arthur’s self-containment will get all shook up. You can only hope that will they get along, and that nothing untoward will bring either of them down.

Some serious stuff however, does emerge. Although December 2009 is reaching its conclusion, Arthur’s past darkens his thoughts. He’s not been a happy guy for quite a few years. He was unable to make much of difference back in Peace Movement days and he feels failure. Plus his roots are tangled, a disapproving father, an alienated ex-wife and a distant daughter. He can only reflect on all that went wrong. We hear his thoughts, although he won’t reveal his inner self to anyone else.

Throughout the substantial first act, Letts fine, perceptive dialogue makes it clear how and why the playwright could have garnered a Pulitzer Prize, even though this and August Osage County are miles apart in spirit and atmosphere. Here, much seemingly light stuff transpires on the surface, but the characters have depth and dimension. The dialogue, sometimes salty, raucous and funny seems bound to make you like everyone. Menace, however, looms

The second act has more serious developments. Letts has Arthur and Franco sometimes at serious odds, reveal their own inner complexities, nearly bonding as if father and son, even as Arthur explores his own relationship with his father.

Letts has written some very good, often amusing comments about race and nationality (Russian and Polish). And he’s well set-up the awkwardness of attraction between Arthur and policewoman Randy. Ultimately, moving moments may catch your throat.

The cast makes this work to its best advantage, even in the less prominent roles, adding a solid sense of a perfectly blending ensemble. Credit director Susan Baer Collins for making it so, with natural timing and pacing, getting her performers to act and react truthfully. And you’ve got to hand it to Jens Rasmussen for his staging of a knock-down, drag-out fight. If you’re seated close-up, pull in your feet.

The set by Matthew D. Hamel adds to the feeling, with its brick walls, rusty overpass and the genuine look of a worn-out shop which modern times have passed by.

Alas, as usual, the Playhouse program book gives no information about the person who created what’s being performed. Letts not only got a Pulitzer for August: Osage County, he was nominated for another with 2003’s Man From Nebraska, seen here at Bluebarn in 2008. He also wrote Bug and Killer Joe along with their screenplays plus that of August: Osage County.

Letts did not write this year’s CBS series’ lighter take on the characters and situations of Superior Donuts; he’s been busy as an actor, quite established portraying CIA director Andrew Lockhart in Showtime’s Homeland, for which he has been nominated for two Screen Actors Guild Awards. Letts also has had roles in TV shows such as Judging Amy, Seinfeld, Early Edition and Home Improvement.

In feature films, Letts has been in Guinevere, U.S. Marshals, Chicago Cab, Straight Talk, The Big Short and Indignation. and often on stages, including Broadway where he won a Tony portraying George in a 2006 Broadway production of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Bet your bottom dollar, you’ll lose your blues. Superior.

Superior Donuts runs to June 4th, Howard Drew Theatre, Omaha Community Playhouse, 6915 Cass St. Thurs–Sat.: 7:30 p.m. Sunday: 2 p.m. Tickets $22-$36. www.OmahaPlayhouse.org

Here’s a review of Silent Sky at Bluebarn Theatre:

This is National Women’s History Month. And a part of that history is on view at Bluebarn Theatre in Lauren Gunderson’s Silent Sky. The focus is on real American astronomer Henrietta Leavitt who, in the early days of the 20th Century, shed new light on how to measure distances between the Earth and faraway galaxies. She also posited that there were multiple galaxies at a time when male astronomers didn’t take that seriously, nor her, nor women in general.

It sounds like a subject worth exploring. But a play about it is not likely to come easily. How do you stage such a flow of ideas that would make down-to-earth drama? Gunderson tries to pull it off, circling around the science by adding a romantic connection between Leavitt and fictional Peter Shaw and also regularly interconnecting with elsewhere composer-sister Margaret via letter readings. Parts of this, especially in the first act, most feels like an earnest dramatized documentary. The second act moves better and has the virtue of some good lines and well-expressed insightful observations about human behavior.

Director Susan Clement-Toberer and her excellent cast do a lot to give this heft and interest while set and lighting designers Martin Scott Marchitto and Darrin Golden have some bright ideas.

The rather minimal set dovetails with a script which seems designed to not overburden theatre groups with extra expenses, including a larger cast. Five characters can’t make up for elements which would give more textual and physical substance. Marchitto’s suggestion of the office Leavitt shares with two other women justifiably looks barren and utilitarian, but, given Leavitt’s apparent lack of personal color, something more detailed would make this livelier. More women. More activity. And the character of Shaw, apparently a suggestion of male attitudes at the time, looks like a slightly comic sketch than a real person. Initially he rushes into and out of the office, minimally and almost indifferently talking about what his boss and colleagues feel about such women while at their own more serious work. Gunderson has Shaw perfunctorily telling about these ideas rather than having them personified at greater length by actual men, diminishing the effect.

Certainly, as written and played, Shaw comes across as awkward and inhibited, not as intelligent as one would expect for someone on the staff of the Harvard Observatory. Perhaps something of a nerd, which might suggest a good match for Henrietta. Yet, she seems less nerdy than he, focused intensely, almost solely, on her constant fascination with studying and analyzing the universe (yes!). In this case the real person here has even less obvious personality than the fictional one.

At certain points along the way, Leavitt speaks directly to the audience, as if in a lecture, talking eloquently about the multiple meanings of her multiple discoveries. This shows her as a more interesting person. She thinks. She expresses her thoughts, even if we are not often shown much detail about what she feels. There is also the wonderful and resonantly relative inclusion of a reading of Walt Whitman’s “When I Heard the Learn’d Astronomer.” (Below the review.)

The two biggest roles offer major challenges to Haley Haas and Christopher Joel-Onken as Henrietta and Peter. Opening weekend they didn’t seem able yet to add much dimension on their own.

As Henrietta’s colleagues Annie and Williamina, on the other hand, Pamela Chase and Judy Radcliff came across well. Chase made Annie look convincingly stern and strong while Radcliff gave Williamina much charm.

Gunderson is the most produced living playwright in the nation for the 2016-17 season, according to American Theatre magazine. In her mid-30s, says the Boston Globe, she is “an adventurous writer who marries playful whimsy with a spirit of intellectual inquiry and engagement with our times.” She’s also written many other plays about real people, about science and spin-offs from Shakespeare. E.g. Ada and The Engine, EMILIE: La Marquise du Châtelet Defends Her Life Tonight, Toil and Trouble, We Are Denmark and Exit- Pursued by a Bear. http://laurengunderson.com/

Marchitto and Golden have provided a beautiful and inventive light array towards the play’s conclusion. They also devised a stage backdrop of a glowing, sometimes winking star map, a good visual enhancement, although Henrietta doesn’t seem to look at it or refer directly to it. It always stays in place, as if suggesting that the Earth is standing still.

This script needs much more to get it going.

Silent Sky runs through April 15th at Bluebarn Theatre, 1106 South 10th St. Thursdays to Saturdays at 7:30 p.m., Sunday April 2nd at 6 p.m. Sunday April 9th at 2 and 6 p.m. Tickets are $25-$30. www.bluebarn.org

When I heard the learn’d astronomer,

When the proofs, the figures, were ranged in columns before me,

When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide, and measure them,

When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room,

How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick,

ill rising and gliding out I wander’d off by myself,

In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time,

Look’d up in perfect silence at the stars.

Walt Whitman 1867

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

An earlier review: Around the World in 80 Days at Omaha Community Playhouse:

A hard-working, talented,earnest cast and director Carl Beck do a lot to make the best of Mark Brown’s stage adaptation of Jules Verne’s Around the World in 80 Days at Omaha Community Playhouse. Despite appealing performances, the script slogs along rather than zips. Brown spends too much time having the characters talk about the action instead of finding ways to portray it, also adding redundant exposition. Moreover Beck and Scenic Designer Bryan McAdams’ sets and projections don’t do enough to vivify would could be an imaginative and distinctive tale.

Brown’s telling seems to be in favor of literalness rather than having a point of view calling attention to the story’s potential absurdities. One would hope that this might be a trip full of laughs, akin to Patrick Barlow’s four-character send-up of the Alfred Hitchcock film The 39 Steps.

Consider the premise. A member of the English idle rich, Phileas Fogg, mingles and mixes with many cultures in his travels but remains singularly unaware of who they are. His only concern seems to be on how much time it takes to accomplish what he’s set out to do. You’d also think there’s be a sense of frenzied urgency suggesting entertaining anxiety. Not in this case.

In Brown’s version, Verne’s Fogg, whose name is appropriate to his cloudy indifference to his surroundings, remains boringly unflappable. Gray amid potentially colorful people and events in which he is immersed. Thus those people and events need broad definition with loony dialogue, as if sending them up from a blinkered English point of view, making Fogg’s attitude comic, surrounded by alien lunacy he doesn’t notice.

Certainly this kind of world-wide travel sounds fascinating. From England to Egypt to India to China to Japan to the USA, often by ship, sometimes by train. Potentially quite an adventure. Just looking at the well-conceived map displayed on stage makes it so.

Given that all of these places and means of transport are suggested by minimal props and sets, calling attention to these limitations suggests something quite funny. However, the naiveté behind them, Verne’s actually, requires more than a simple presentation. Brown’s dialogue could also stand more deliberate laugh lines.

Brown gives too much talk and presence to Scotland Yard Detective Fix, who believes Fogg to be responsible for a recent major bank robbery and follows him along with Fogg’s valet Passpartout wherever they go. Fix becomes as much a part of the story as they. Certainly the detective could be a goofy, sinister and absurd comic person who pops up from time to time, but not so often.

One important and likely part of the fun is in having three actors portray a multitude of characters whom Fogg and Passpartout encounter along the way. Ben Beck stands out making the most and best of quite an array, full of comic variety. His accents, postures and voices become a show in themselves. It looks as if he’s having fun. You will watching him. As Fix, plus others, Monty Eich always seems adept. Teri Fender, who eventually appears as Aouda, an Indian widow rescued from immolation, also has a few bits before that. She carries on gamely.

Problems lie in wait for Anthony Clark- Kaczmarek and Ablan Roblin as Fogg and Passpartout. The shallow cartoons they play lack shading. Which means they and Beck have to find ways to create distinctive characterizations of some kind. They nearly get there. When having the chance in the plot, Clark-Kaczmarek conveys appealing, almost boyish charm. Roblin provides a vigorous take on his role. If only he and Eich wouldn’t shout so often.

Beck’s serviceable direction needs major help from his design team, although Georgiann Regan has come up with great costumes, including those which have to be quick changes for multiple characters.

Many more specific projections are needed, full of people and buildings, e.g. obvious ones such as a pyramid for Cairo, the Taj Mahal for India, a bowl of rice with chopsticks for China, stampeding buffalo outside the windows as a train crosses American plains (as in the original story) . That train’s open windows, by the way, look out on no passing landscape, just something like clouds. Rather primitive. Oh. If you’re wondering about travel by balloon, an enduring image, there is none in this version. “There’s no balloon in my script,” wrote Brown. “The (1956) film had a balloon. It’s what everyone remembers. But there’s no balloon in the book” http://www.colonytheatre.org/shows/AroundtheWorldIn80Days.shtml

Audio enhancements would also help. Gongs at Hong Kong, for example. Gongs which would shock the travelers. Props could be goofier and less realistic as if calling attention to the idea of a low budget, or by being assembled on stage. Beck doesn’t do enough to make this look more interesting, or, instead, to make fun of the limitations.

The Sunday afternoon I attended an almost full house rarely resounded with solid laughs. There were always smatterings. It is possible that that audience, as any other, could have trouble understanding much of what is said in the very-well coached and articulated variety of accents on stage. The cast handles those challenges with skill.

As often the case at many local theatres, there is no program book information about the writers who created the material being performed. Regarding Brown, he also wrote a stage adaptation of Fielding’s Tom Jones and of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince, came up with his own story in The Trial of Ebenezer Scrooge and more. (http://www.markbrownwriter.com/).

Jules Verne is likewise disregarded. That novelist, playwright and poet is best remembered for Journey to the Center of the Earth, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, The Mysterious Island, Master of the World and much more. Further information is at http://julesverne.org/

The cast and Beck certainly have their work cut out for them. Too bad Brown didn’t give them something better.

Around The World in 80 Days keeps on going through February 12th at the Hawks Mainstage Theatre, Omaha Community Playhouse, 6915 Cass St. Performances are Wednesdays through Saturdays at 7:30 p.m. and Sundays at 2 p.m. Tickets are $18 to $36.

Share this: