According to a Youth Custody Report, in October last year, the population of the secure estate for children and young people, for under 18 was 920- an increase of 40 from the previous month and 45 compared to the previous year. It may be decades on from the publication of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist, but these statistics presented in the Youth Custody Report from 2017 suggest that even today juvenile crime is still a concern.

It was due to the publication of Dickens’s Oliver Twist, as well as other ‘Newgate novels’, like William Ainsworth’s Jack Sheppard, that society’s concern with juvenile delinquency increased. This is addressed alarmingly by R.H. Horne, who suggested that ‘among all those who had never heard such names as St Paul, Moses, Solomon, etc. there was a general knowledge of the character of and course of life of Dick Turpin the highway man, and more particularly of Jack Sheppard, the robber and prison breaker’. A particular concern for the authorities was pick-pocketing, the crime of choice among the Artful Dodger and the other members of Fagin’s gang, which Henry Mayhew branded ‘the daringest thing that a boy can do’.

Whilst Oliver Twist may be a work of fiction, the rise in crime in Victorian society was a harsh part of reality. This is evident when, through searching The Old Bailey Online, I found 832 cases of pickpocketing between the years 1838-40– many of which had been committed by children.

So, what led children to become criminals?

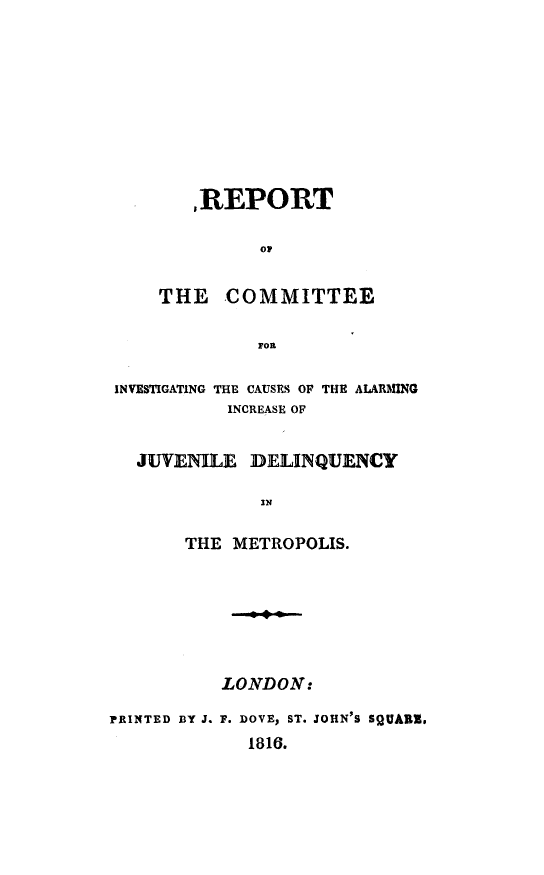

According to the 1816 ‘Report of the Committee for Investigating the Causes of the Alarming Increase of Juvenile Delinquency in the Metropolis’, the main causes of crimes committed by young people were supposedly the ‘want of education’, the ‘want of suitable employment’, the ‘violation of Sabbath’ and the ‘improper conduct of the parents’.

An image of the 1816 ‘Report of the Committee for Investigating the Causes of the Alarming Increase of Juvenile Delinquency in the Metropolis’

An image of the 1816 ‘Report of the Committee for Investigating the Causes of the Alarming Increase of Juvenile Delinquency in the Metropolis’

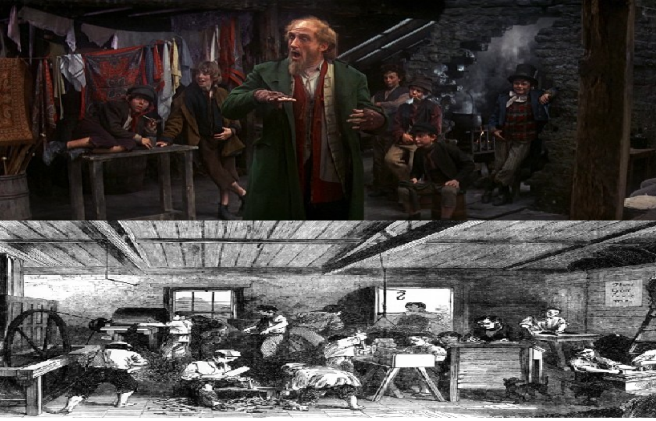

A cause for crime in Oliver Twist is the setting of Fagin’s den. Located in the Saffron Hill district of London, Fagin’s den is seen as ‘the emporium of petty larceny’ (Dickens, 1839)- a place where juvenile crime actively takes place and is even encouraged. In his Hand-Book of London, Peter Cunningham describes Saffron Hill as a neighbourhood that was ‘densely inhabited by poor people and thieves’. Dickens described Fagin’s den as ‘…a very dirty place’ which is ‘dismal and dreary’ (Dickens, 1839), perhaps mimicking the traditional Victorian workhouse.

A comparison image of a depiction of Fagin’s den in the 1968 film version of Oliver Twist and the traditional Victorian workhouse

A comparison image of a depiction of Fagin’s den in the 1968 film version of Oliver Twist and the traditional Victorian workhouse

The children in Oliver Twist do not receive proper education, or proper forms of employment. Instead, they are taught by Fagin to become thieves. The harsh reality of being part of Fagin’s gang of thieves is illustrated by Nancy when she says to Fagin, ‘I thieved for you when I was a child….It’s my living, and the cold, wet, dirty streets are my home; and you’re the wretch that drove me to them…’ (Dickens, 1839). Nancy recognises that she is bound to a life of crime ’till I die’, reflecting how it was difficult for many young offenders to remove themselves from a life of crime.

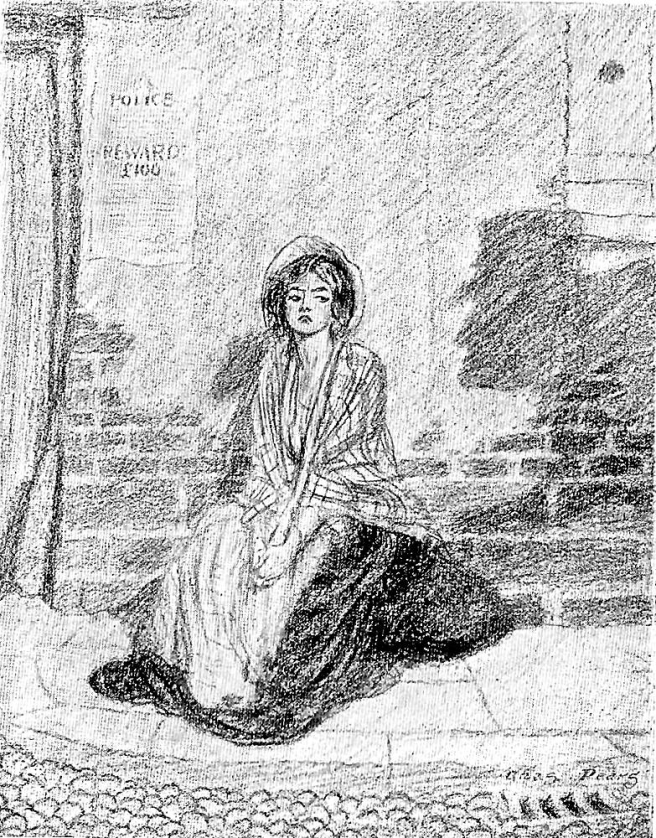

This was reflected in a case I found on the Digital Panopticon website regarding Phoebe Anderson. Like Nancy, Phoebe was young when her life of crime began, having made her first appearance at the Old Bailey when she was 16 (accused of purchasing goods with a counterfeit coin). After six months imprisonment at Newgate, she found herself charged again in 1839 with coin offences and was later transported to Tasmania. Dickens’s fictional female thief, as well as cases like Phoebe’s, contradict Heather Shore’s suggestion that juvenile delinquency was a ‘male problem’ and that females criminals could only be ‘the standard role of prostitute or criminal moll’. Phoebe proves to be the anthesis of the traditional female criminal, just as Dickens’s Artful Dodger is the anthesis of the traditional Victorian boy.

An image of Dickens’s Nancy, by Charles Pears for The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Centenary Edition (1912)

An image of Dickens’s Nancy, by Charles Pears for The Adventures of Oliver Twist, Centenary Edition (1912)

Dickens’s Artful Dodger is particularly interesting when looking at the subject of juvenile delinquency. In some ways, he fits with the definition of larrikin: an Australian term, popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, meaning ‘a boisterous, often badly behaved young man’. As Helen Rogers states, The Launceston Examiner suggested that juvenile criminals were ‘filthy in his person and his talk, bordering on the idiotic in his absence of ideas, a very coward in his nature. As larrikins perhaps did, The Artful Dodger displays elements of being ‘filthy in his person and his talk’. This is due to Dickens’s use of cant slang, which were various words or phrases spoken by members of the 19th century criminal underworld. There is evidence of the Artful Dodger using such language in his first meeting with Oliver, when he says ‘Hullo, my covey! What’s the row?’ (Dickens, 1837). This again links back to suggesting that juvenile criminals were a product of their environment, as the Artful Dodger adopts various language patterns from the adult characters in the novel.

A particularly interesting case I found when researching the topic of juvenile delinquency was that of Samuel Holmes. Like the Artful Dodger, his involvement in the criminal world began at a young age, as he was imprisoned aged 13, later tried and transported to Van Diemens Land in 1836. What I found extremely interesting about Samuel Holmes was how much his life appeared to mirror that of Dickens’s Artful Dodger. This became evident when I came across an 1835 report by William Augustus Miles, who had interviewed Holmes along with other boys as he awaited transportation. What particularly stood out to me was that, like the boys in Oliver Twist, Holmes was ‘kept by a Jew’ and after a ‘fortnight’ of training he ‘went out to assist and screen the boys where they picked pockets’. Though both Holmes and the Artful Dodger are similar in the fact that they are a product of their social background, after gaining his certificate of freedom in 1848, Holmes became obscure whereas the Artful Dodger remains a popular figure decades after the publication of Dickens’s novel.

M.D Hill stated that ‘the delinquent is a little stunted man already’, which is evident in the Artful Dodger’s character as he has ‘all the airs and manners of a man’ (Dickens: 1837). According to Margaret L. Arnott, ‘sharpness, boldness, intelligence and firm nerves were common characteristics in representations of juvenile boys’which she goes on further to say ‘was tempered by the concerned perception that such boys were displaying a premature mature and/or engaging in behaviour that detached them from childishness’. This was evident in the case of John Leary, a 14-year-old recidivist, who preferred to stay in the prison yard rather than go to the schoolroom. So perhaps, using this evidence, young male criminals adopted adult qualities and became ‘stunted men’ because that was how they were expected to be – just as female criminals were associated with being ‘molls’ or prostitutes.

Not only did juvenile delinquents act like adults, they were often treated like adults. This is evident as, until the early 20th century, children were subjected to the same punishments as adults including hard labour and capital punishment in some cases. This changed in the late 18th century, which Heather Shore suggests ‘marked the most significant shift in the ways youth were prosecuted and punished’. Reformatory Schools soon replaced harsh punishments, and emphasis was placed on shelter, refuge, care and education.

“The Probationary Ward School”, Illustrated London News (13th March 1847)

“The Probationary Ward School”, Illustrated London News (13th March 1847)

Something which has stood out to me when browsing several records on the Old Bailey and the Digital Panopticon is the lack of justice for the juvenile criminals, with many facing transportation or death for what would today be called ‘petty crimes’. Oliver Twist, overall, can be read not only as an exploration of juvenile delinquency but also as Dickens’s criticism of the injustice of the criminal system.

Bibliography:

Primary Sources

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist, London, 1839.

Hill, M.D. Practical Suggestions to the Founders of Reformatory Schools, 1835.

Cunningham, P. Handbook of London: past and present, Vol.1, 1849.

Report for the Committee for Investigating the Causes of Alarming Increase of Juvenile Delinquency in the Metropolis (1816)

Horne, R.H. Children’s Employment Commission, quoted by Fredrick Engels ‘The Conditions of the Working Class in England (1845)

Mayhew, H., London Labour and the London Poor, (1851)

Digital Panopticon (www.digitalpanopticon.com, 2017, accessed 10/01/18) Information regarding Samuel Holmes https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-1676-18350706

Digital Panopticon (www.digitalpanopticon.com, 2017, accessed 10/01/18) Information regarding Phoebe Anderson https://www.digitalpanopticon.org/life?id=obpdef1-100-18381126

Secondary Sources

Arnott, M.L. Gender and Crime in Modern Europe, Routledge (2002)

https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/larrikin (accessed 10/01/18)

Horn, P. Young Offenders: Juvenile Delinquency from 1700 to 2000 (2010)

Rogers, H. Conviction blog: Artful (2017)

Shore, H. ‘Artful Dodgers-Youth and Crime in early 19th century London’ (2002)

https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/youth-custody-data

Advertisements Share this: