The intention at this time of year is to hunker down and read. Somehow that never quite happens. Hours of escapism are sacrificed for the more immediate concerns of constant clearing up, juggling invitations and the sociability of cosying around a warm television in the room where the Christmas tree twinkles. Alcohol and constant snacking tends me rather to sleep than to my trusty Kindle. Like European football, I recommend a winter break in January, just so the nation can bury its head in a book or three. Jeremy Corbyn, take note!

As a kid I devoured books. Quite literally. There was not an endless supply, although we had boxes full of jumble sale relics in the coal shed, and the public library was but a hop, skip and jump away. I thumbed, spine-cracked and dog-eared the best beloved volumes; they no doubt looked as if they had received some canine attention.

I knew it instinctively then, but it took me decades to process and articulate. There is an intrinsic truth that speaks to you from the best writing. You know it lives in you, changes you, that you are forever touched by its presence. Later, in this internet age, you realise these books were not really written for celebrity or financial reward. There were no writers’ blogs to demystify the source of the magic, no photographs to persuade you that the author was somehow more important than the words. No, these words stood by themselves, and very often – as with Tolkien, or Kipling or Richard Adams – they were birthed from a profound love for their children.

The proof of the pudding is in the eating. I have returned to these books frequently. At different times in my life they have been digested differently. When I passed them on to my children, hundreds of hours snuggled amongst the duvets and pillows, they acquired a renewed and profound significance. They formed part of the greatest gift I could consciously bequeath.

You can look them all up on Amazon, read the reviews on Goodreads. There is no substitute for the time invested in entering these worlds. They are individual, quirky, unforgettable. Some are well known, so I won’t dwell on Tolkien and CS Lewis here. Watership Down, forgotten now by the Hary Potter generation, I reread whilst backpacking in India. For me this is England, my country, my home; the love of the countryside resonates in every page. The Satanic Mill (now published as ‘Krabat’) oozes menace and the supernatural in a forgotten middle Europe. Similarly Susan Cooper’s quintet, this time infused with the myths of Arthur and old Gramarye. The Minipins I guess is ‘fantasy’ (which can be a dirty word) but the charm and oddness of the characters will win you over immediately.

And then there is Tove Jansson, writer and artist extraordinaire.

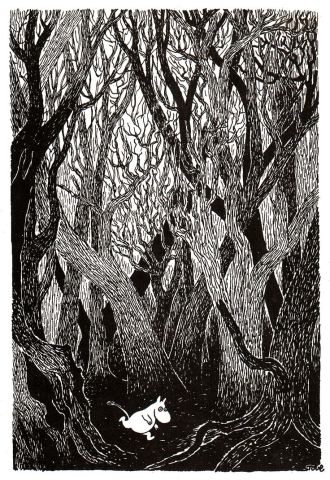

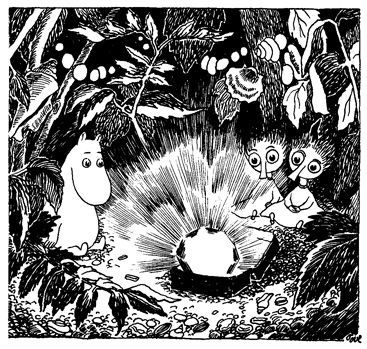

I could let her global endurance speak for itself, because indeed it does. Her universal appeal speaks volumes. So many people, reading in so many different languages, have discovered what I, wide-eyed and curiously piqued, first unearthed as a callow seven-year old, and wondered what on earth it all meant – these odd little creatures, their funny little idiosyncrasies and obsessions, the clarity of their existence. First there was a Comet in Moominland, then a Hobgoblin’s hat, the mysterious Hattifatteners, a floating theatre, a midwinter wonderland, the lonely old Groke, Snufkin’s disappearances…

And then it all began to get a bit… how to explain… melancholy and darkly existential… Moominpappa suffered a midlife crisis and forced the family to up sticks to go and live on a remote island with a lighthouse… A whole book is set in the Moominhouse when winter is approaching; various old friends and new creatures arrive for comfort and succour, only to be met with the family absence, an atmosphere thick with the confusions of bereavement and abandonment… Do they ever return home? We think so, but…

Much has been written about how Tove Jansson turned her life into art. She drew on the characters she loved to inform the characters we love so much in her books. She lived through the tragedy and trauma of the twentieth century, but her art and writing is suffused with joy and hope, all located in the little details that would give us such fulfilment if only we too stopped to smell the roses. Written for adults, The Summer Book is full of tenderness, wisdom and (here comes that word) truth. Its deceptive shining simplicity weaves a quiet spell you are unaware of until you gasp, breathless with realisation that, as Philip Pullman succinctly puts it: ‘Tove Jansson was a genius.’