December 15, 1939, marked a turning in interpretation and image of the American Civil War. Perhaps one could argue that the turning point had started earlier in 1936 when the novel that inspired the movie hit shelves across the nation, beginning a tidal wave that would eventually envelop the globe. That December night in Atlanta, thousands of people lined the streets and hundreds packed into the theater. As the movie’s title – Gone With The Wind – scrolled slowly across the screen against a background of a vivid Technicolor sunset, the moment had come when a story came to life and challenged the historiography of the Civil War.

December 15, 1939, marked a turning in interpretation and image of the American Civil War. Perhaps one could argue that the turning point had started earlier in 1936 when the novel that inspired the movie hit shelves across the nation, beginning a tidal wave that would eventually envelop the globe. That December night in Atlanta, thousands of people lined the streets and hundreds packed into the theater. As the movie’s title – Gone With The Wind – scrolled slowly across the screen against a background of a vivid Technicolor sunset, the moment had come when a story came to life and challenged the historiography of the Civil War.

This is an arguable turning point. It did not occur during the 1860’s. It was not a literal battle. It was not even pretending to be a comprehensive look at the conflict. However, Gone With The Wind influenced the way domestic and international societies view the American 1860’s, staged a battle of ideology and interpretation, and evolved into an education on the war and reconstruction. With epic influence, this movie managed to captivate audiences with its entertainment factors and teach them a one-sided so-called history lesson that continues to haunt many today.

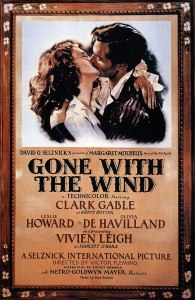

“Gone With The Wind” movie poster (Public Domain)

As entertainment, Gone With The Wind, deserved many of its accolades. It was the Star Wars of its day – if that comparison is permissible – with crowds lining up around the block to get tickets. This movie drew millions to the theaters during the Great Depression era and showed them struggle, grit, and a vow that “tomorrow is another day.” Filmed in Technicolor on lavish sets, the motion picture thrilled the audiences. As Vivien Leigh (Scarlett O’Hara) flirted on the screen, she represented the capstone of a national “search for Scarlet” that had consumed the entertainment world and fan magazines for months prior to filming. Clark Gable (Rhett Butler), Leslie Howard (Ashley Wilkes), Olivia de Havilland (Melanie Wilkes), and Hattie McDaniels (Mammy) starred impressively in 1930’s filmmaking. Epically, Gone With The Wind grossed millions at the box offices, leaving many people delighted with the adaption of a novel that some had called The American Classic.

At the center of The Wind storm lived the author, the instigator: Margaret Mitchell. She liked to portray herself to the media as an Atlanta housewife who wrote a book in her spare time. However, she took writing more seriously than that, having worked for a local newspaper in Atlanta for several years, gaining popularity as a journalist before troublesome health forced her to live more secluded. Mitchell researched extensively in the Atlanta archives and remembered her youthful conversations with Confederate veterans and former Southern belles; she liked to emphasize that her story was accurate. Parts of it are. Other parts do not match further historical research. Clearly, Mitchell researched and wrote from a strictly Southern perspective, drawing on tradition and heritage for inspiration, too. The book includes painfully racist remarks (which were omitted or toned down for the movie version) and an incredibly sympathetic view of the Confederacy and the Southern situation during the Reconstruction Era, leading modern readers to wonder where the boundary lines lie in historical accuracy in fiction.

Whether the skewed perspective was intentional or not, Mitchell’s book of romance and strictly Southern interpretations became widely popular. Her publisher launched one of the largest national publicity campaigns, and book clubs, reporters, and other market and consumer influencers approved the book, pushing concerned or dissenting voices to the sidelines. When Hollywood entered the scene, director David O. Selznick reimagined the story – reducing the political and ethnic situations in the book – and created a “simpler” romantic story set during the Civil War and Reconstruction Eras.

Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh as Rhett Butler and Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone With The Wind”

On the surface, it is easy to imagine that Gone With The Wind is just a story set during the 1860’s. However, the passing decades have shown the movie’s reinforcement and creation of myths about the Civil War. The ideas of happy plantations, contented slaves, flirtatious belles, and “cavaliers” play out in the movie, underscored by a large dose of Lost Causism. Ironically, Scarlett herself hates the war and Lost Causism, creating a strange conflict between what the book and movie actually present and what fans take away.

Because of the multiple Academy Awards, staring cast, and a plot that resonated well with people across the world, Gone With The Wind became the unofficial public history education source for many on the topic. As the drama played over and over on television and home entertainment, its grip on the mind strengthened. Clearly, with its one-sided portrayal, this interpretation of the Civil War did not qualify as balanced information, but in many circumstance, the entertainment value routed accuracy. Interestingly, in many foreign countries, Gone With The Wind is seen as American history – something beautiful, romantic, and charming. That veneer masks the other side of the story, the part that for decades was neatly kept hidden away: the horrors of slavery, the abuse of women, the positive efforts during The Reconstruction, just to name a few. The truth – as usual – tends to be found between the two extremes of the story and the dark side of history.

Gone With The Wind built an empire of a story that has wriggled its way into many topics related to the Civil War – battles, clothing, women’s studies, Black history, Southern image, Lost Causism, medical studies, blockade running, Reconstruction, and economics. This presents a double-edged sword for historians and educators and recognizing the threat and opportunity is crucial.

The famous Civil War movie threatens a clear understanding of the war because of its perspective and interpretation. Unfortunately, through the generations, many viewers accepted the film as relatively accurate, propagating many misconceptions about the conflict and mid-19th Century Southern society. Historians must delve into the book and the movie to be able to understand the perspective, be able to explain the ideology behind the plot, and be willing to discuss what other research has revealed, countering the myths.

On the other hand, historians and educators may find it useful to utilize the movie’s influence as a way to engage. Without endorsing the featured Lost Causism and suspect history, it can be used as starting point for a discussion. For example, I have had many foreigners approach during living history events and want to know if I am “a Southern belle like Scarlett” – rather than scolding, it has been useful to realize that their knowledge of Civil War women comes from that movie and then provide accurate (primary source based) information about the experiences of women during the war. I have also found that people don’t always know what blockade runners are, but if I mention Rhett Butler, Paris, and the green bonnet, it gives a little connection and then I can explain the historical details to an interested audience.

Gone With The Wind’s premiere in 1939 represents a turning point in how America and the world envisioned the Civil War. Some of it is accurate, other parts leave much to be desired in historical details. As historians, educators, or history enthusiasts, it is important to recognize the impact this movie has had, acknowledge the historical and ideological problems, and realize that the film’s influence can be used to teach accurate history to an audience who is obsessed with Scarlett’s version of “War, war, war!”

Share this: