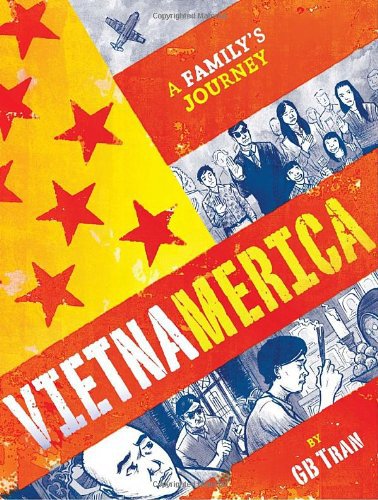

I liked the somewhat sardonic voice of the rather nebbish-looking narrator of Vietnamerica, GB Tran, who gave up on teachers and fellow students in South Carolina pronouncing Gia-Bao in a way not painful to his ear. GB was American-born, that is, “second generation” Vietnamese-American, without even childhood memories of Vietnam and wars there.

The graphic memoir he wrote and drew shows him struggling to learn about (never mind understand!) a very complicated history. Unremitting war against foreign armies (Japanese, French, American) and emigration by GB’s parents and older siblings made the Vietnamese life related in flashbacks difficult. The flashback-filled narrative is further complicated by the multiple marriages up the family tree (family trees are shown branching downward on the page) and by a lot of moves within Vietnam, as well as emigrations to France before the unification of Vietnam.under repressive communists.

One of GB’s grandfathers, Do Ty, was a an army physician for the Viet Minh, GB’s father was a teacher in South Vietnam, GB’s father’s younger brother, Vinh, was drafted into the South Vietnamese army, etc.

The characters have varying views in the present about the wars and the regime that followed. The ones who got out, including GB’s parents maintain some nostalgia for a world that no longer exists, some post-traumatic stress disorder from the dangers of the 1960s and 70s in Vietnam. GB portrays himself as having been just fine with his parents’ reticence about telling him about what they and other family members experienced in Vietnam before or after the 1975 fall of Saigon.

The family tree on page 62 is helpful for reminding the reader of who’s who—or some of who’s who in that there are a few important characters not on the family tree.

The drawings are engaging. The number of cells per page ranges from .5 (something extending to the facing page) to 12. My guess is that the mode is 7.

I have read a number of books written by generation 1.5, that is by writers mostly or entirely educated in the US who were born in Southeast Asia and fled as children, mostly with their parents. The parents seem to their children to be inscrutable — or at least very unwilling to talk about their past in any detail — and the narrators struggle to find out what happened and what the survivors felt. (For a female-centered graphic memoir see Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do.)

There is less about growing up markedly different in America in Tran’s book than in some others written by members of the 1.5 generation. Though ego-centered, his book is about his parents’ and grandparents’ generation rather than what he experienced or remembers. What they experienced was very dramatic, and more fraught with danger than growing up in South Carolina was. Perhaps a memoir of what Tran remembers rather than elicits lies ahead. I hope so, though appreciating the need to find out where he came from in sociohistorical terms, not just geographical ones (though a map would have been almost as useful as the family tree is!)

(It’s odd that there are not (or none that I know of) memoirs by the first generation in that many of those who got out in 1975 were fluent in English. Jade Ngoc Quang Huynh (South Wind Changing) is close, having being 18 in 1975 and emigrating after “re-education”) by the communists).

©2011, 2017, Stephen O. Murray

Advertisements Share this: