I am by no means an etymologist, but I do find word origins fascinating. Take the word smog, for example.

Smog itself — a combination of smoke and fog — has afflicted humankind for thousands of years, but the word describing it seems to have begun in London in 1905. According to an article in Journal of the American Medical Association that year, a health expert, possibly Dr. H.A. des Voeux, treasurer of London”s Coal Smoke Abatement Society, used the term “to indicate a frequent London condition, the black fog, which is not unknown in other large cities and which has been the cause of a great deal of bad language in the past. The word thus coined is a contraction of smoke fog “smog” — and its introduction was received with applause as being eminently expressive and appropriate. It is not exactly a pretty word, but it fits very well the thing it represents, and it has only to become known to be popular.”

The word smog is a portmanteau, a word that blends the sound of two different words. Lewis Carroll, famed author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, coined the word portmanteau to describe the kinds of words he invented for his delicious poem, “Jabberwocky.”

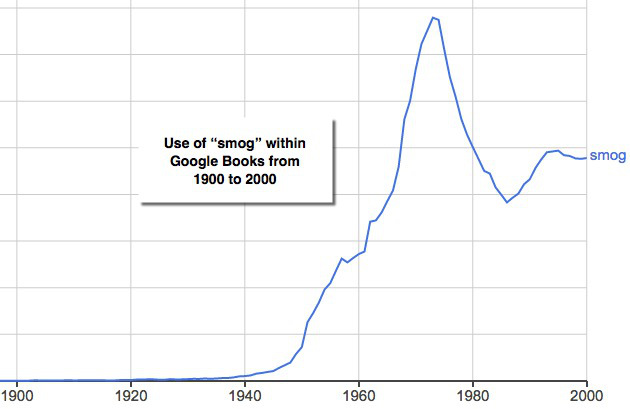

Aside from rare use among scientists, the word smog virtually never appears in print until the 1940s, when its use spikes, almost certainly as a result of the Donora tragedy in 1948. Interestingly there was no such spike in the 1930s, when 60 people were killed in a smog event in the Meuse Valley in Belgium. There is no separate word for smog in Dutch, nor in French or German, the three most prominent languages used in Belgium. The greatest likelihood of smog not peaking in the 1930s is because the word hadn’t been in use enough even in scientific literature until that time. For instance, the word fails to appear in a 1937 article in The Journal of Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, called “The Fog Disaster in the Meuse Valley, 1930: A Fluorine Intoxication.” The article uses instead “fog,” “smoke,” and “thick mist.”

The word begins to register, but barely so, in the late 1930s, climbs a bit in the early 1940s, and really begins to soar from 1948 through the 1960s. (See chart, below.)

The word climbed steadily in use until 1966, when suddenly its use skyrocketed. During six days in late November that year, Manhattan was flooded with smog, leading to the death of an average 24 people per day. Like the Donora smog, the Manhattan smog was caused by pollutants trapped near earth’s surface by an extended temperature inversion.

The word smog kept rising until its peak in 1972, two years after Congress passed the Clean Air Act of 1970, the most comprehensive anti-pollution measure to that date. Since then use of the word has trailed off, but smog itself remains a common and important topic of conversation, even — and perhaps especially — today.