So long-time, no book reviews right? Unfortunately a combo of long days at work, lots of standing on my commute and being shattered in the evening and watching Love Island, my reading has somewhat suffered. However, I have read some books since my last post, and you can find out more about them below…

Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel Garcia Marquez (trans. Edith Grossman, 1985, Penguin)

If, like me, you’re familiar with the title of this novel but not its content; Garcia Marquez’s famous novel tells the story of Fermina Daza and Florentino Ariza. As teenagers they fall in love, until Fermina decides that her feelings are just infatuation, and marries the well-connected and esteemed Dr Juvenal Urbino. Despite her marriage, Florentino dedicates his life to maintaining his love for Fermina.

This is a novel whose name is something of a misnomer. If you go into this novel expecting a love story, you will be probably disappointed. This is a story that explores the complicated relationships that exist between men and women, from contentment to sexual desire.

The three protagonists are all generally well-drawn. Dr Urbino is shown sympathetically despite being the ‘antagonist’ to the central relationship. Fermina is gloriously stubborn and free-willed. However, Florentino was the character that I did have a problem with. Whilst his youthful romantic infatuation with Fermina is quite sweet, the fact that he continues this obsession is pretty unsettling. As he gets older, his relationships with other women are similarly disconcerting, and a couple leave a very nasty taste in my mouth. I spent a lot of the novel unsure as to whether we were supposed to be rooting for someone I felt was pretty horrendous.

The novel is stunningly written; starting at the end, recounting the final day of Dr Urbino’s life and Florentino appearing to declare his love to Fermina; with Marquez then unpicking their history. His writing is beautifully descriptive, bringing to life the society they live in, the streets they walk down and the homes they sleep in.

All My Puny Sorrows by Miriam Toews (2014, Faber & Faber)

TW: Suicide

This novel is the story of two sisters, Elfrieda and Yolandi, who grow up in a small Mennonite community in Canada. When the novel opens, Elf is a world-famous pianist, performing across the world and loved by everyone who knows her; Yoli is in the midst of a second divorce, messy affairs and attempting to write a book. And Elf has made yet another attempt to kill herself.

Told from Yoli’s perspective, this novel is an emotional and raw exploration of what it means to live, the different types of love and what happens when you try to force someone to fight. Toews uses a brilliant, almost stream-of-conciousness style; you truly feel like you are in Yoli’s head as she struggles between empathy, love and rage towards her sister.

All the characters are wonderfully drawn, Yoli and Elf as the central characters feel the most ‘real’, but their mother is also a wonderful character; their Aunt Tina whose own daughter committed suicide; Nic, Elf’s husband who is trying desperately to save her…the entire cast of characters are just brilliant; and their fight to defeat the sadness around them is very well done.

This book is, however, deeply, deeply sad. Whilst the writing keeps you engaged, I couldn’t help feeling like I was intruding on someone’s grief. This is perhaps due to the fact that the novel is semi-autobiographical, but I did just feel deflated every time I read this.

Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen (1817, Wordsworth Editions)

This was the first novel that Austen wrote, but wasn’t published until after her death. It tells the story of Catherine Morland, a young woman who moves with family friends to spend a season in Bath where she experiences various social embarrassments until making a good match in marriage (of course).

There are some really acerbic moments in this novel ,I did enjoy the narrator’s scathing commentary on society’s norms, the traits which are attractive in women, and on society’s lack of appreciation of the novel. I also enjoyed how Catherine’s love of Gothic novels was played up, and how this lead to her understanding of reality becoming blurred.

I did, however, find that Catherine was just a bit of a wet blanket and impossibly dim. Her complete lack of awareness of other people’s motivations was infuriating for me. At every plot point I just wanted to give her a firm shake of the shoulders. My personal favourite character, Isabella Thorpe, was probably supposed to be the antagonist but she had some of the wittiest lines, and seemed to be the character that Austen had the most fun with.

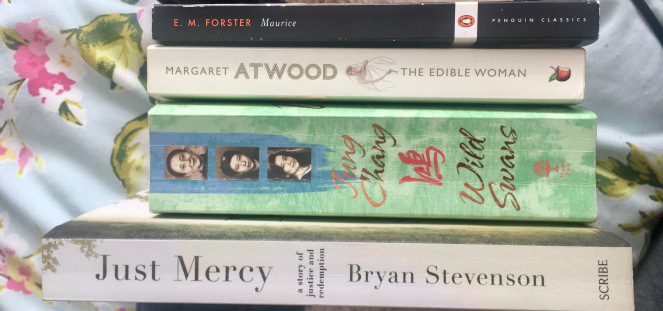

Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China by Jung Chang (1991, Harper Perennial)

I’d owned Wild Swans for years before I finally picked it up to read; and I’m so glad that I have finally read this. Jung Chang explores the life of her grandmother, mother and reflects on her own childhood through some of the most tumultuous years in Chinese history.

This is an incredibly engaging way to essentially have a fascinating lesson in history. Despite it’s size and increasing importance in world politics, I knew embarrassingly little about China’s history. From her grandmother’s world of courtesans and and strict class lines; to the at first liberating and then terrifying rule of Chairman Mao, Chang is very good at bringing all these time periods to fascinating life. I was particularly interested in the way Chang captured how people (including her parents & herself) were genuinely bought into Mao’s way of seeing the world, and the dangers of what happens when people begin to challenge the world that they have been encouraged/forced to see.

I also appreciated Chang’s focus on the women in her family; whilst her father was a key figure in Chinese regional government, the role of women throughout history has often been glossed over, and Wild Swans really explores how often the women is Chang’s family have had their lives uprooted by men, and how they managed to be entirely flexible and responsive to the challenging circumstances they find themselves in.

Maurice by E.M. Forster (1971, Penguin)

Written in 1914, but published after Forster’s death, Maurice is a really beautiful book which explores being gay at a time where this was still illegal in the UK. The title character, Maurice, is a young man from a privileged background who is generally pretty unremarkable, aside from his increasing realisation that he is attracted to men. The novel focuses on two relationships; one with his Cambridge contemporary Clive, and one with Clive’s gamekeeper Alec.

This is a really beautifully written novel, which captures Maurice’s confusion and his ultimate acceptance of himself as a man who is attracted to other men. Its passages about romance also are great at capturing the pains of first love; with the added complication that Maurice is feeling.

I feel like few people have really heard of this novel, and it is really worth a read.

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice & Redemption by Bryan Stevenson (2014, Scribe)

I always feel like a bit of a cliche when I describe books as important, but Just Mercy is an important read.

Bryan Stevenson is a lawyer, and director of the Equal Justice Initiative based in Montgomery, Alabama. Just Mercy is a combination of memoir, exploring his career as a black man committed to avoiding miscarriages of justice, and an argument for a more just criminal justice system in the United States, particularly in the South.

Stevenson particularly focuses on the death penalty as an example of just how far gone the system is, and also on the issue of young people having their entire futures taken away; either through capital punishment or life-long prison sentences. Both of these tend to be punishments given more to those from non-white backgrounds and those who are poor. Stevenson illustrates his points with cases that he worked on; he doesn’t shy away from some of his clients having committed crimes, but that the system rarely recognises the individual circumstances of defendants. The main case study, of Walter McMillan, who is sentenced to death for a crime he is adamant he didn’t commit, is threaded throughout the book.

I cried tears of sadness, anger and happiness reading Just Mercy, and would really, really love it if you read it too. For a taster, you can listen to Bryan Stevenson’s Desert Island Discs interview here.

Love by Toni Morrison (2002, Vintage)

I was a little apprehensive picking up Love, as my last experience with Toni Morrison was Beloved, which I didn’t adore. However, I’m glad I did read this, as it has really made me want to try again with Morrison.

Love follows several women whose fates are tangled with that of Bill Cosey, the deceased owner of a once hugely popular hotel and resort. There’s May, his daughter-in-law who keeps the resort going until her decline into conspiracy theories; Christine, her wayward daughter; Heed, Christine’s childhood friend & Bill’s second wife; Junior, a new arrival to town who is drawn towards the Cosey women; Vida, a former employee at the resort and L, the resort’s former chef.

The novel tumbles between the characters, as their past are revealed, and the desire for revenge that has simmered for years threatens to burst to the surface. Morrison is great at writing interesting if deeply unlikeable characters; and creating an idea of place that feels very true.

Our Endless Numbered Days by Claire Fuller (2015, Penguin)

When Our Endless Numbered Days was released, it was a lovely that just seemed to be inescapable, so I am a little late to this particular party. The novel follows Peggy who, aged eight, is taken by her survivalist father into a forest somewhere in Europe, where they will live in a hut; under the belief that the rest of the world has disappeared.

The book follows Peggy’s journey to the hut, the years she spends with her father in the hut and her ultimate escape from living with him, and her return to her Mum and England.

Peggy’s an engaging character, whose view of the world both in the hut and when she returns, is really interesting. The descriptions of the natural world are also really good; and Fuller is also great at depicting Peggy’s father as a combination of scared, loving and also increasingly sinister.

I did like this book, and I found the ending great, but I do feel like this was a book that was a victim of its hype.

The Edible Woman by Margaret Atwood (1969, Virago)

The Edible Woman is Margaret Atwood’s debut novel, written when she was just in her mid-20s. The novel focuses on Marian, a young woman who is perfectly ordinary. She has a job working for a market research company and has a perfectly appropriate lawyer fiancee. However, as their marriage becomes more of an impending reality to Marian her body appears to fight back.

There are some really interesting ideas within this book; particularly that of identity and what happens to a woman when she gets married. The novel moves from first to third person; and there are plenty of musings of female identity compared to various forms of literature. There’s some commentary around men and women using each other, and the different outcomes this has for each gender.

The general atmosphere of the novel reminded me a lot of the section of The Bell Jar where Esther is doing her internship in New York; particularly the wooziness of the world of work and descriptions of food.

Whilst you can really see the potential that Atwood will really explore in later novels, this does feel like it’s trying to do too much in relatively few pages, and the ending is definitely in keeping with Atwood’s later style

.

Amy

Twitter | Instagram

Advertisements Share this: