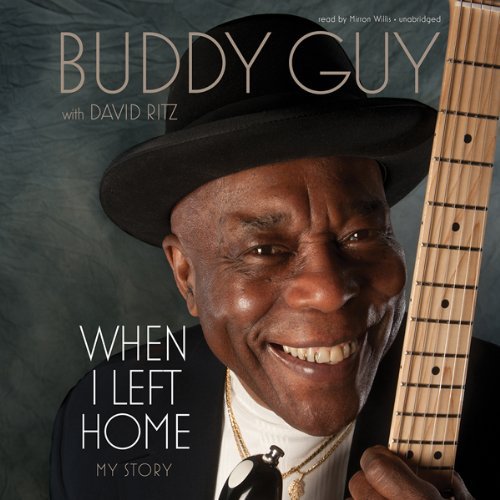

“Heaven is lying at Buddy Guy’s feet while listening to him play guitar.” — Jimi Hendrix

I’m going to begin this review with a story of my own. It’s directly related, so bear with me. In June of 2004, I attended Eric Clapton’s Crossroads Guitar Festival at the Cotton Bowl at Fair Park in Dallas, TX. I consider this the day I got my best education in the blues. I’d grown up listening to blues, jazz, rock, country, folk, and just about everything else in my life. Growing up in the country, the radio was my lifeline. Music was in my blood, always has been. But somehow, impossible as this seems to me now, I’d missed the name Buddy Guy. On one of the three stages kept in constant rotation (meaning one setup was being torn down and one was being put into position while the third was in use), B. B. King was slated to play for a mere 10 minutes. It’s not that he didn’t deserve more — of course he did. The moment his attendant put Lucille in his hands, the crowd gave him a standing ovation. He was in poor health, and his doctors told him not to overdo it. But he got out there, and he was having so much fun, his health improved right before our very eyes. And knowing it would jack with the packed schedule of the all-day event, he asked the audience both for forgiveness and for 10 more minutes. Those 10 minutes were again renewed with wild enthusiasm, ultimately stretching to an hour. During that time, King had been joined on stage in an impromptu jam session that included Eric Clapton, Jimmie Vaughan, Buddy Guy, and John Mayer. It was as though the gods had stepped down from Olympus. King proudly declared this jam to be the highlight of his career and thanked the audience once more for indulging him before making his exit. While the audience was still roaring, but after enough time had passed to offer due respect, Buddy Guy busted into a lick so funky you could smell it. Clapton, Vaughan, and Mayer all stopped dead in their tracks, giving the elder bluesman his moment to shine. And there was an acknowledgement there. It’s not that Guy wanted the spotlight so much as he simply believed the show had to go on, and he wanted to play with the man on stage who, at that point in his career, was just picking up the baton for the new generation: John Mayer. The stadium went dead silent while emotions I can’t even begin to describe grabbed my nerves. Guy looked over at Mayer, that silent invite that says, “Let’s see what you can really do.” Mayer hesitated briefly, but after a big smile from Guy, he took the cue, and the two went back and forth in a blues duet the likes of which I’ve not seen nor heard, before or since. It was the stuff of legend, as they say: the kind of things you tell your grandkids about, and they tell you you’re lying. Clapton and Vaughan slowly backed away in respect. At the end of that session, Mayer laid his guitar at Buddy Guy’s feet and walked off the stage in deference. Guy, humbled, choked back with some indignation, muttering something about how he didn’t deserve that.

Thing is, he did deserve it. He earned it and more besides over a lifetime of dues and a dedication to the sound that had liberated his soul. You could feel it that day. That was how I discovered Buddy Guy. That was the day I learned to truly appreciate the blues. At the time, I felt cheated that I’d not discovered him before, but as introductions go, I was more than grateful for this one. Not only did I never forget that lesson, I was able to apply it to every piece of music I listened to from that point on, kicking all of my appreciations up yet another notch. The more I applied it, the more the blues grew. I appreciated the honesty of it, its directness. The blues don’t lie. And as Buddy Guy himself says in the preface of this book:

“Funny thing about the blues: you play ’em cause you got ’em. But when you play ’em, you lose ’em. If you hear ’em — if you let the music get into your soul — you also lose ’em. The blues chase the blues away. The true blues feeling is so strong that you forget everything else — even your own blues.”

That was the gift Buddy Guy gave to me (and probably a few thousand people just like me) that day: a true understanding of what the blues was really about. It’s like making medicine from a poison, the power of humanity to heal itself from the hurts of the world. The lesson was firsthand on that stage. It was impossible not to enjoy myself the rest of the day, regardless of the blistering sun that afternoon or the rain and lightning storm that moved in late that evening. Stagehands frantically disassembled the stage as midnight approached, while ZZ Top kept playing away despite warnings not to, and despite the high winds that threatened to push them into the crowd. Everyone that day played at top capacity because all of them had been inspired and reinvigorated by the performance of Buddy Guy. Every last one of them had said so in turn, that he had tapped into the roots of what made the music special, beyond the commercialism, beyond the fame, beyond anything else. Everything was secondary to the love of the music and the desire to share it with those next in line to appreciate it.

That story ran a bit long, but hopefully I conveyed even a measure of that small moment in time. I saw mastery tempered by humility. I heard magic tempered by humanity. I witnessed true greatness, with all of its simplicity and flaws. And that’s what brings me to this book. I recently read Tom Graves’ book about blues legend Robert Johnson, and as is only right and natural in my world, the music followed suit. And then it spiraled out to other blues masters in my personal collection, and Buddy Guy made his obligatory appearance in relatively short order. I thought back to that day at the Cotton Bowl and started wondering, “What’s his story?” If I’m being honest, I know that fundamentally, many bluesmen of that generation have similar stories (legends of crossroads bargains notwithstanding), but sometimes it’s not about the story itself, it’s how it’s being told, and about the details that make those stories unique to the person telling them. Music’s like that too. So it stands to reason that if Buddy Guy’s music sets him apart from his contemporaries, why not his ability to tell his story in his words?

To know a master’s influences is to begin learning his story with common understanding. Buddy Guy explains here his first influences in John Lee Hooker on 78 vinyl and the cowboy songs of Gene Autry on film. As he tells it, the day he left home is a kind of second birthday; the life before that day was one thing, the life after something else entirely. Upon his arrival in Chicago, he ended up under the wing of Muddy Waters, to whom this book is dedicated. The stories unfold to the end of the book, each with a personal human touch of triumph and tragedy, of magic and music, always with a sense of belonging that comes from never forgetting one’s roots. It’s less of an autobiography and more of a memoir, the kind of thing where it feels like each of the stories told could be related to you from a front porch with a cracker barrel and a couple of rocking chairs, guitar in hand, of course. I suspect that’s not far off from how this book was put together, with Guy simply telling his stories into a recorder, and his co-author David Ritz putting the spit and polish on it to turn it into the final book. In the end, the book validates for me what I’ve come to previously understand about Buddy Guy: the man and his music are one and the same. It couldn’t be otherwise. The only real difference is the book is the story behind the story, the wisdom of a man who has lived his life and wants to pass it down to those who’ll hear it, just as he has done with his music. If you love the blues, or if you seek to understand them, this book is for you.