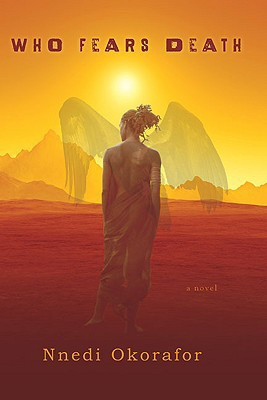

Another book-club book, but one I was very much intending to read anyway. It’s the same author as The Book of Phoenix, though this is the earlier work, and I believe The Book of Phoenix is meant as a sort of prelude, to explain why the world of Who Fears Death is as it is.

Another book-club book, but one I was very much intending to read anyway. It’s the same author as The Book of Phoenix, though this is the earlier work, and I believe The Book of Phoenix is meant as a sort of prelude, to explain why the world of Who Fears Death is as it is.

The book is set in a nebulous, post-apocalyptic future, in Saharan Africa (though we are not given much more detail than that at the beginning), and has elements of near-future tech, mixed with a strange sort of technological absence. It hovers in the background, making a mess of any attempt to guess precisely when the novel is set.

Partly, this is to background the technology of the setting, because in many ways, the setting is not the point in that regard. Primarily, this is a story of a journey. It’s a story of people, and their relationships, and the difficulties of growing up not only different but outcast entirely. It’s a story of being a woman in a society that does not treat its women well. And it’s a story about being who you are, despite what comes around you. And, in many ways, it’s a story about destiny, prophecy, and whether or not the future is inevitable.

And I really rather liked it.

It is consistently obvious that the author is drawing on a different tradition than the same-old same-old pseudo medieval Europe we’re used to. She has Nigerian heritage, and has spoken in interviews about how this has influenced her work, and it shows – not that I am in any way qualified to spot it in that way, but there’s a strong sense of a tradition and a history pushing through, for all that it’s not one I’m familiar with. The magic, the tradition, and the way people form their societies speak to someone drawing on many many myths, and it makes me want to read more about where Okorafor got her inspiration. Obviously, in part, this different set of traditions is enticing simply because it is different – it’s refreshing to read something apart from what you’re used to. But it isn’t simply novelty that keeps the reader entertained – there’s a real intuitive feel to the way Okorafor portrays magic – magic that she emphatically doesn’t explain – and a beauty to the way she describes things.

I think that’s one of her major strengths – I found her a very vivid, visual writer, whose descriptions really set the scene for me. She gives you her setting in all your senses, and it is so, so easy to find yourself sucked in, really feeling the world she has created. And I think that’s the main reason it’s such a page-turner – because it’s so immersive.

Which is good, because the characters kinda sour that. I mean, I know she’s trying to write (and succeeding) very realistic, human, flawed characters. And I’m not going to say she doesn’t. My main issue is… I wasn’t rooting for any of them. I didn’t love any of them. And especially the main love plot felt… exasperating. Because you totally see why they’re together, what they see in each other… but they’re also really not very good for one another, and it’s just… painful to read. I want them to realise that there are better people out there for each of them. But they remain each other’s One True Love, and it’s infuriating. Which I guess is rather the point. All the relationships Okorafor gives us are Difficult in some regard, and bring to the fore problems both personal and societal – the way the female lead is patronised by the main male character, the way she’s prevented from learning magic because of the ego of the magician – because Okorafor fundamentally knows what she’s doing and what she wants to say. It just sometimes isn’t very Fun.

But hey, sometimes we don’t need fun. Sometimes we need an exploration of the repurcussions of female genital mutilation on the behaviour and psyches of teenage girls. To be honest, and this sounds weird, this was possibly the best bit of the book for me. Okorafor describes the event viscerally and horrendously, but manages to make the reader see why the characters choose to undergo it, and that they come out of it not immediately against the whole process. They form a bond that lasts a long way into the book, and the friendship that’s forged by going through FGM together is a huge aspect of the plot, as well as something of a saving grace for Onyesonwu, the main character, who has spent her life an outcast up until this point. But at no point is the FGM painted as a good thing – more, Okorafor is highlighting the lengths to which Onye has to go to fit in, to make herself acceptable to those around her, and it’s painful and horrifying and yet completely comprehensible.

Then we watch as the girls grow up, and see how their sex lives – and essentially their freedom as human beings – has been curtailed by this, and as they go on their journey, as they become free-er, this still holds them back. And in some ways, the magic is a metaphor for the FGM, and in some ways, the FGM is a metaphor for the way society has treated them. For all that I don’t particularly care about any of them, I do care about watching the way they interact, the way they have to deal with the fallout of what has been done to them their whole lives, the people they’ve been made to be, and how this contrasts with the people they want to be.

Freedom is… a huge theme that runs through the novel, alongside the inevitability (or not) of destiny, and I really think the way it saturates everything is totally compelling. It makes me want to read more of Okorafor’s work.

I gave this four stars and defended it vigorously in book club, and the lost one was simply because I had no characters to love. There’s a very obvious reason she’s won the BFA and WFA, and I will definitely read more by the author, and soon – I hear the Binti series is good…

Next up, House of Names, which alas, for all that it too is a literary author doing Greek mythology, it can’t hold a candle to Bright Air Black.

Advertisements Share this: