by NONA BLYTH CLOUD

There are some people who begin to hear the ticking of the clock louder and louder in their lives, that relentless reminder that death is somewhere up ahead. They study it, try to pry at death’s secrets, and if they are writers, they chronicle it.

Claudia Emerson (1957-2014) wrote a lot of poems with death in them, not in a resigned or a morbid way, but exploring with words her encounters with its many faces, from the bones of a bird to the ending of a marriage, and the cancer treatment which ultimately failed to keep her alive.

_____________________________________________

BoneIt was first dark when the plow turned it up.

Unsown, it came fleshless, mud-ruddled, nothing

but itself, the tendon’s bored eye threading

a ponderous needle. And yet the pocked fist

of one end dared what was undone

in the strewing, defied the mouth of the hound

that dropped it.

. . . . The whippoorwill began

again its dusk-borne mourning. I had never

seen what urgent wing disembodied

the voice, would fail to recognize its broken

shell or shadow or its feathers strewn

before me. As if afraid of forgetting,

it repeated itself, mindlessly certain.

. . . . . . . . Here.

I threw the bone toward that incessant claiming,

and watched it turned by rote, end over end over end.

Louisiana State University Press

_____________________________________________

_____________________________________________

The next poem comes from a collection she opens with this epigraph:

Memory believes before knowing remembers

– William Faulkner

Student ConferenceAt first, I mistook the small, black tattoo

. . for a phone number or a date jotted

In haste on her wrist’s paler underside –

. . then suspected stitches when it didn’t fade.

I was not far wrong. (Her poems: careful,

. . deliberate, thin as she was, haunted by a mother

years dead – not a word about the brief grief

. . of the father who saw in her a worsening

resemblance.) I imagined what it took

. . for her to enter the parlor, where nothing –

garish bird, snake, broken heart – could tempt her,

. . turning from the small, determined letters:

think. The word she had purchased moved faintly

. . in what she must have thought would be

permanence about her pulse, her body’s argument

. . to think what she wished she could still feel,

arm bared for another coming

. . into being, the needle’s indelible sting.

Louisiana State University Press

_____________________________________________

EphemerisThe household sells in a morning, but when

they cannot let the house itself go for

the near-nothing it brings at auction,

the children, all beyond their middle years,

carry her back to it, the mortgage now

a dead pledge of patience. Almost emptied,

there is little evidence that she ever

lived in it: a rented hospital bed

in the kitchen where the breakfast table

stood, a borrowed coffee pot, chair,

a cot for the daughter she knows, and then does not.

But the world seems almost right, the near-

familiar curtainless windows, the room

neat, shadow-severed, her body’s thinness,

like her gown’s, a comfort now. Perhaps

she thinks it death and the place a lesser

heaven, the hereafter a bed, the night

to herself, rain percussive in the gutters—

enough. But like hers, the light sleep of spring

has worsened—forsythia blooming

in what should be deep winter outside

the window—until it resembles the shallow

sleep of a house with a newborn in it,

a middle child she never saw, a boy

who lived not one whole day (an afternoon?

an evening?) sixty years ago in late

August. And as though born without a mouth,

like a summer moth, he never suckled

and was buried without a name. She had waked to that—

that cusp of summer, crape myrtles’ clotted

blooms languishing, anemic, the cicadas

exuberant as they have always been

in their clumsy dying.

This middle-born

is now the nearer, no, the only child.

The undertaker’s wife has not bathed

and dressed him; the first day’s night instead

has passed, quickening into another

day, and another, and he is again awake,

his fist gripping a spindle of turned light,

and he is ravenous in his cradle of air.

“Ephemeris” from The Opposite House: Poems, © 2015 by Claudia Emerson,

Louisiana University Press

_____________________________________________

These last two poems are from Late Wife, which won the 2006 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry.

AftermathI think by now it is time for the second cutting.

I imagine the field, the one above the last

house we rented, has lain in convalescence

long enough. The hawk has taken back the air

above new grass, and the doe again can hide

her young. I can tell you now I crossed

that field, weeks before the first pass of the blade,

through grass and briars, fog — the night itself

to my thighs, my skirt pulled up that high.

I came to what had been our house and stood outside.

I saw her in it. She reminded me of me —

with her hair black and long as mine had been —

as she moved in and then away from the sharp

frame the window made of the darkness.

I confess that last house was the coldest

I kept. In it, I became formless as fog, crossing

the walls, formless as your breath as it rose

from your mouth to disappear in the air above you.

You see, aftermath is easier, opening

again the wound along its numb scar; it is the sentence

spoken the second time — truer, perhaps,

with the blunt edge of a practiced tongue.

Most of the things you made for me—blanket-

chest, lapdesk, the armless rocker—I gave

away to friends who could use them and not

be reminded of the hours lost there,

not having been witness to those designs,

the tedious finishes. But I did keep

the mirror, perhaps because like all mirrors,

most of these years it has been invisible,

part of the wall, or defined by reflection—

safe—because reflection, after all, does change.

I hung it here in the front, dark hallway

of this house you will never see, so that

it might magnify the meager light,

become a lesser, backward window. No one

pauses long before it. But this morning,

as I put on my overcoat, then straightened

my hair, I saw outside my face its frame

you made for me, admiring for the first

time the way the cherry you cut and planed

yourself had darkened, just as you said it would.

“Aftermath” and “Frame: An Epistle” from Late Wife, © 2005 by Claudia Emerson, Louisiana State University Press

_____________________________________________

Claudia Ann Emerson was born on January 13, 1957, in Chatham, a “one-stoplight town” in the southern part of Virginia. She graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in English and returned to Chatham, where she was a part-time mail carrier and managed a used-book store.

She wrote songs from a young age, but she was inspired to write poetry by reading Rainer Maria Rilke’s “Letters to a Young Poet,” a book she discovered in the store where she worked. Emerson applied to and was accepted for the University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s creative writing program, earning a master’s degree in 1991.

In 1994, she was hired as an English professor at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg VA. Emerson was Poet Laureate of Virginia from 2008 to 2010. In 2013, she joined Virginia Commonwealth as a creative writing professor.

On December 4, 2014, Claudia Emerson died from colon cancer at the age of 57.

Though much of her work is “dark,” her clarity of perception lights up the words, like a modern-day illuminated manuscript.

_____________________________________________

Selected Bibliography- Impossible Bottle: Poems (published posthumously – Louisiana University Press, 2015)

- The Opposite House: Poems (published posthumously – Louisiana University Press, 2015)

- Secure the Shadow (Louisiana State University Press, 2012)

- Figure Studies: Poems (Louisiana State University Press, 2008)

- Late Wife (Louisiana State University Press, 2005)

- Pinion: An Elegy (Louisiana State University Press, 2002)

- Pharaoh, Pharaoh (Louisiana State University Press, 1997)

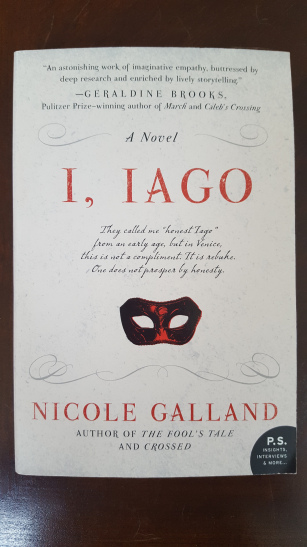

- Old cornfield

- Tattoo parlor window

- Forsythia

- Night view of a house from tall grass

- Wooden-framed hall mirror

- Claudia Emerson

Word Cloud photo by Larry Cloud

Share this:- More