Daydreaming of other worlds

To write, you need words.

To write well, you need a vocabulary—preferably, a large one. And this isn’t so you can show off and write about sitting in a puddle of your own mucilage while bound in a brodequin and tortured in a tenebrous tower.

Readers have it easy: they’re given context for each word and it’s usually sufficient to intuit a meaning. Writers have to pluck a precise word and understand most of its denotations and connotations and create a fitting context (all of which happens simultaneously); therefore, writers need access to a wide roaming ground, plentiful in detail and depth, and an effective search method.

The roaming ground metaphor offers little when it comes to nonfiction writing (expand your vocabulary in the relevant direction; if you write about fish, go explore the lake), or when it comes to fiction writing set in the real world (expand your vocabulary in the relevant direction; if you write murder mysteries set in a Bedouin camp, go explore the desert).

But when it comes to writing anything set in a world of your making, where you are God, where you give names—what happens to your roaming ground?

You can keep expanding it by learning concepts, but eventually you’re going to have to invent names for that new plant, that new race, that new arcology. You’ll even have to invent verbs and adjectives (somehow new adverbs seem to be the rarest). Two questions present themselves:

- How does one invent?

- How does one invent, coherently? (Because it’s likely you’ll need more than one word.)

The words you invent are the writer’s quirk words (as opposed to the reader’s quirk words)—they enrich the boundaries of language in general, not just the boundaries of a reader’s vocabulary.

How far would you roam to find the perfect word?

The final spark of invention is an intensely private affair—no one can share the warmth of your light, even if they can see its glimmer—but there is at least one common approach to conceiving the perfect neologism in fantasy: search for and use (modified) old-fashioned English words.

(I assume English as the starting point, but the same should apply to any rich, evolving language with a centuries-long tradition.)

One reason to choose amongst old words is that their sounds are already entrenched in the English language. Their echos still rebound between mouthes and ears, riding in derived words, modified morphemes, and historical associations. They are fragments of the past that can be made to evoke the past, evoke a parallel world, or evoke various modernities or futurities. (Just think how in real life a blog was a weblog was a ship’s blog was a log-line used for measuring boat speed in knots starting in the sixteenth century.)

Of course, it depends what the goal is for your new world. If you are trying to sound foreign or exotic, you should probably build on words from a foreign language or choose deliberately exotic combinations. For example, in his book Spell it Out, David Crystal offers a brief discussion of some of these exotic sequences.

(The examples and observations are his; the ordering, the selection, and any mistakes are mine.)

Vowels:

- doublings of a, i, or u, such as in aardvark, leylandii, muumuu,

- triplets of vowels such as in taoiseach or rooibos,

- four vowels such as in Hawaiian.

Consonants:

- starting a word with ng such as in ngaio, (the principle is that we expect ng at the end of a word, such as in sing, but not at the beginning),

- starting a word with ll such as in llama (same principle, we expect it in full)

- ending a word with j such as in raj (we expect to see j at the beginning, not at the end)

- ending words in v (Kiev), in k (anorak), or z (pince-nez),

- starting with combinations such as in knesset, ptarmigan, straffito, svelte, sjambok, kvetch, czar, zloty, tsunamy, bhaji, dhow, khaki, rhinoceros, zho,

- ending with combinations such as in ceilidh, ankh, sheikh,

- doublings such as in hajj, qawwali,

- triplets of consonants such as in chintz, schmaltz, veldt,

- quintuplets of consonants such as in bortsch, shchi,

- seeing a qi or a qa, such as in quigong or quadi.

Plain weird:

- words beginning with wu, kw, skr, zl that immediately stand out (examples from Dr Seuss).

And there are more!

If dipping into foreign languages is searching far and abroad, and dipping into Old English is searching far back, then you have the options of stepping further back (going to Latin, Greek, Sanskrit) or stepping sideways into unusual punctuation (like E. E. Cummings), or even just staying within the confines of the language but creating your own meld-compounds.

Ultimately, coherency of invention stems from coherent neologising—so if you pick a method and a source, stick with it.

But let me return to using archaic English words.

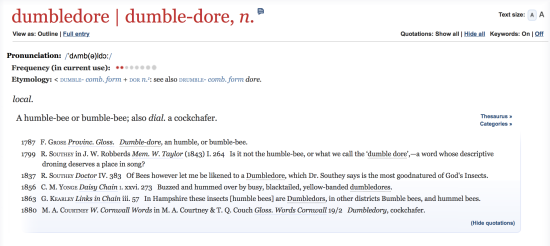

J. R. R Tolkien invented whole new languages, but he didn’t make them out of thin Shire air; he started with Old English (amongst others). More recently, J. K. Rowling needed a few names, and she too roamed wide afield and far into the past. Indeed, in preparing for this article, I accidentally came across the source word for one of her character names: Dumbledore.

According to Wikipedia: Rowling stated she chose the name Dumbledore, which is an Early Modern English word for “bumblebee”, because of Dumbledore’s love of music: she imagined him walking around “humming to himself a lot”.

Dumbledore alongside another three hundred other uncommon words in Mark Forsyth’s Horologicon (2012). Forsyth likes to hunt through arcane and regional dictionaries for quaint words, which he groups and connects and weaves into a narrative interlarded with outrageous British humour. (The Horologicon forms a “trilogy” with The Etymologicon and The Elements of Eloquence, the last of which partly inspired this blog.)

I don’t know how Rowling alighted on the word dumbledore itself: she might have learned it at some point and recalled it at the relevant time, or she might have thought bumble-bee and looked up archaic synonyms. An effective—and efficient—middle way between knowing it all and looking it up is reading books like Forsyth’s Horologicon or Etymologicon that are aimed to amuse, and yet are crammed with terms and monikers and helpful connections and word-building templates (e.g. vespers, vespertine, advesperate, vesperal, vespertilionize, vesperty). He even often includes creative nonce-uses of words. Study his examples and follow their lead.

Other options for creative boons:

- perspective-bending and dark humour dictionaries like The Devil’s Dictionary by Ambrose Bierce,

- thesauruses with a twist that jog your brain sideways like The Thinker’s Thesaurus by Peter E. Meltzer,

- fun etymology troves like Balderdash & Piffle: One Sandwich Short of a Dog’s Dinner by Alex Games,

- compendiums of mythological creatures like The Book of Imaginary Beings by Jorge Luis Borges that’ll also make you question whether you were creative enough in your world-building,

- magazines like Nature, which also illustrate how names can be appropriated from one domain of life into another.

Vespertine scene

I’d like to end this last full post of the year on a lighter note.

Have you ever thought about the word tatterdemalion? There’s something attractive about it, both visually and aurally. Something that brought me to open Tolkien’s Silmarillion, and something that repeatedly sparks a desire to finally read Ray Bradbury’s Dandelion Wine. I think Forsyth nailed the name for it (I mark it in bold).

Tatterdemalion has the lovely suggestion of dandelions towards the end (although pronounced with all the stress on the may of malion) and should be immediately comprehensible even to the uninitiated, because everybody knows what tatter means, and the demalion bit was never anything more than a linguistic fascinator.

A fascinator is a magician, a charming or attractive person, a head shawl worn by women, either crocheted or made of a soft material.

What was that about us running out of original word-pairs? The combination linguistic fascinator has precisely four hits on Google, all belonging to this paragraph in the Horologicon.

And I can’t think of a better phrase to describe a fluid wring of the tongue that can turn being tattered into something so smooth-sounding.

So let’s hear it for all the linguistic fascinators already in the world, and all those to come.

May you invent at least one.

Happy Holidays!

P.S. But what about the dog, the dog in the title?—I hear you asking. Well, once upon a time, a chapter heading from Roy Peter Clark’s Writing Tools stuck with me like a doggy trotting at my heel. The chapter heading is as follows:

Get the Name of the Dog

Clark recounts how journalists are told before going out to collect information that they shouldn’t come back without the name of the dog, or, put tritely: they shouldn’t come back without the telling details, even if those details won’t get used in the final article.

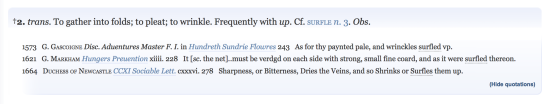

World-building is both easier and harder because you can’t fetch the details, but you can (and perforce must) invent them even if you won’t use them explicitly. The doggy that’s been trotting behind me is a wrinkly, podgy pile of fluffy fur, which I decided to call one of the Horologicon words that caught my fancy: surfle. Can you feel the smooth, thick folds in the word?

From the OED

Surfle? Oh, Surfle! Come back, I’m sorry I said you were no linguistic fascinator.

Please excuse me while I and my pet piggy retrieve Surfle. I believe he’s gone off to play with my husband’s pet boar somewhere in the neighbourhood. You have to understand, the holidays are an especially difficult time for keeping track of one’s imaginary pets with all the real relatives getting in the way. Tut-tut.

Share this: