Over the past decade, it’s become a common sight around the world to see padlocks chained to the sides of bridges. The locks, sometimes engraved, are very often placed there by tourists, who visit with loved ones, and wish to leave their mark on a place.

Most recently, though the locks, known as ‘love locks’, have started to take on somewhat of a sour note.

In 2011, in Paris, France, the locks, which had been appearing on the Pont des Arcs for years, suddenly began to disappear, removed by the City’s maintenance workers. This however did little to stop the tourists, and they began to spread elsewhere, most notably to the Pont de l’Archevêché near Notre Dame, which quickly became over-laden with them.

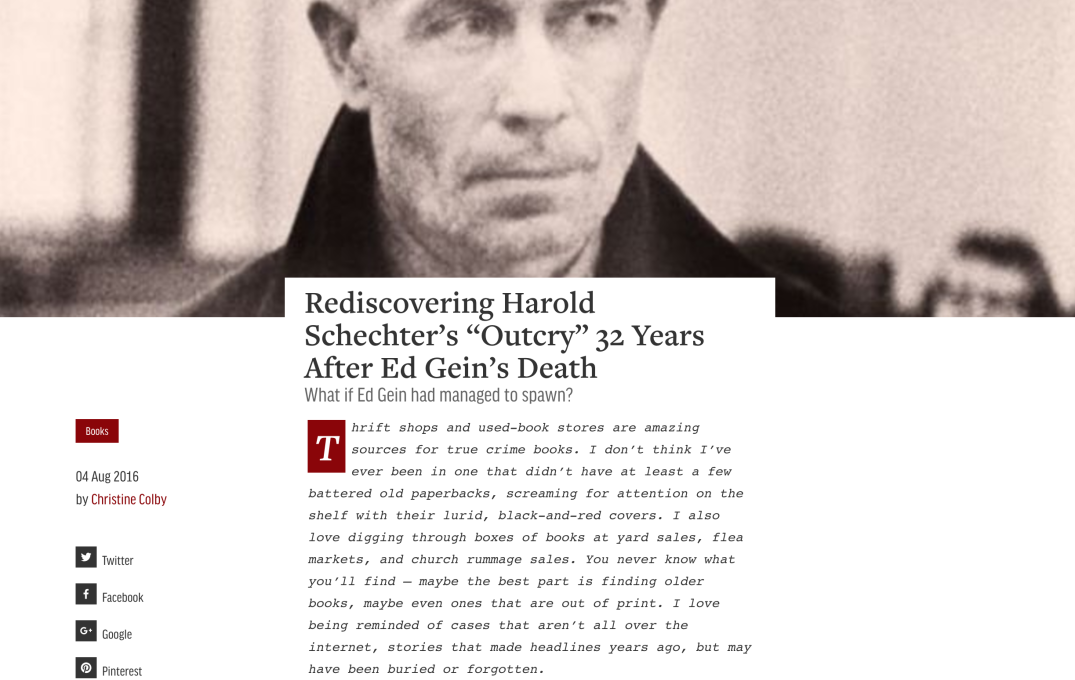

The Pont des Arcs laden with love locks.

Worried about the damage the weight of the locks was causing these centuries-old bridges, in 2014, the Mayor’s Office began to cover the bridges with plexiglass, therefore blocking the railings from reach, a decision which was met with outrage from tourists, who had heard of the tradition and had come to Paris hoping to follow in it’s footsteps.

In actual fact, however, this tradition does not belong to Paris, and instead began, over a century before, in a small medieval town in Western Serbia known as Vrnjačka Banja

It was here, in the early 1900s, that there lived a young woman by the name of Nada, who was working as a schoolmistress in the town. One day, Nada met a local officer called Relja, and they very quickly fell in love, devoting themselves to each other, and promising to stay together forever. They were soon engaged and due to be married, but were interrupted by the threat of war.

In 1914, Relja, eager to fight for his country, left Vrnjačka Banja and Nada behind, for the Serbian front in Greece, but, although young and desperate to make his mark, Relja’s war did not last long. On the 6th October 1915, when the Austro-Hungarian army launched a successful attack on Belgrade, the Serbian’s fight in Greece ended, and he was due to return home to Vrnjačka Banja. But Relja would never return home, for during his short time in Greece, he had met and fallen in love with another woman, from the small island of Corfu, and it is here where Relja was to remain.

Back in Serbia, Nada waited in hope for her long-lost love to return, but her wait was to be in vain, and, as the days passed, she faded more and more, until eventually she died, young and alone, of a broken heart.

Mourning her loss, and terrified of meeting the same fate as Nada, a practice began amongst young girls of the town, where they would write their names, and the names of their loves, on padlocks, thus symbolically tying them together forever, before locking them to a small pedestrian bridge in town.

This practice faded soon after, but, years later, poet, Desanka Maksimović wrote the poem Molitva za ljubav, or ‘A Prayer for Love’, in which she told of the legend of Nada and Relja, and with it, revived the love locks tradition. In Vrnjačka Banja, the practice soon became so popular that the small pedestrian bridge where it had all began was renamed Most Ljubavi: ‘Bridge of Love’.

The love locks tradition still continues at Most Ljubavi today.

Since then, this practice has spread far and wide, to every corner of the globe, but why, in recent times, has the practice spread so suddenly and so far?

The likely culprit is the Italian Young Adult novel, Ho voglia di te. Written by Federico Moccia, and later adapted in a film, the story involves a scene in which, the male protagonist, while trying to woo a girl, makes up a tale about lovers locking a chain around the third lamppost on the Northern side of the Ponte Milvio in Rome, before throwing the key into the Tibor River, to signify that they’ll never leave each other.

The book, which sold over a million copies, brought about a craze of young copycats, and is believed to be the cause of this modern wave of love locks, which has caught on so much that the maintainers of the Rialto Bridge in Venice have now introduced a three-thousand Euro fine for anyone attempting it.

With the fines, the damage, and the outrage, it is sad that a tradition, which began in such a bitter-sweet way over a century ago in Eastern Europe, should ultimately end up causing so much trouble, but, in Paris, at least, this story will have one final happy ending.

Recently, the Mayor’s Office, no doubt in an attempt to placate the tourists’ disdain, and win a few brownie points from locals, announced that it has decided to auction off the love locks that have collected on the city’s bridges over the past few years, and, in doing so, raise money for refugee groups in the region.

Although full details have yet to be announced, it is believed the 10 tonnes of locks will be sold off in clusters of five and ten, and available for anyone to purchase. So if you wish to buy a piece of Parisian history, this may be your chance!

Advertisements Share this: