Q: Are you happy with it?

BW: Yes. In some ways we realized a good portion of the original intent and concept of the film. I think the film could have been much longer and maybe the scope would have boon broader-more characters. But in terms of the central things that it has to say. I’m happy. And I’m happy — after the difficulty being turned down by different sources — to have made that kind of film.

Q: I was talking with Charles Burnett, and he said the ending in the script is much different from the ending in the film. In the script the main character, Charlie Banks, is transformed into a clown. Burnett said it was a problem of money and time.

BW: It was a time problem. But maybe, with all due love and respect, temperamentally for me, this ending is what I saw as organic to the material. I think the flight into another sort of realm — the grotesque, the ironic — that he wrote was wonderful in some ways. But I think the current ending, not necessarily better, but better for what the film is now. It’s an organic ending. I tried to make a synthesis of the original concept and the tone and the reality of the film, as it was realized, as it was accomplished.

Q: I thought it was too open ended. I didn’t know what was going to happen to Charlie.

BW: You don’t. I’ve had people say to me, “I’m concerned that this guy is going to commit suicide.” Then I’ve had people argue vigorously that he’s going home. You see his wife comfort him. You see a portrait of a family with pain, with problems. His wife is steadfast and he’s almost childlike. But you know that man is concerned with his family. So the ending had to be open. This man is asphyxiated. And the only way to deal with asphyxiation sometimes is to move.

Q: It was shown in Washington with two films that are similar in theme. Burnett’s My Brother’s Wedding and Alonzo Crawford’s Dirt, Ground, Earth, and Land. I told some people I’d seen it with that we have to put aside our middle-class prejudices and realize these filmmakers are saying something valuable about people we don’t often see in films.

BW: Among black people in the Sixties, there was a certain amount of populism and a striving for unity, but a unity that in some ways was always imposed by segregation. There was always a differentiation in that. And sometimes we don’t like to acknowledge the differentiation, the varied experience, the stratification, the conflicts, or anything that deal with that. We have to be very careful with that notion of stereotypes. A film that deals with working-class people, then people feel it’s stereotyped, because it’s poor folks.

My concern, and Charles’ concern at that particular time with that film, was to speak about these people and their relationship to the world. Because they are very numerous in our community. Their problems are in many ways the defining ones — not the only ones — but some of the defining ones: the massive unemployment, the difficulty of male-female relationships — which seems to be universal — the maintenance of the family. These are big problems. But they aren’t unique to black people, because they are problems in advanced capitalistic countries as well as underdeveloped countries.

Q: Was it a conscious decision to shoot it in black-and-white with a relatively static camera?

BW: Yes. Inherent in that film and in the text and narrative is the notion that you have to look to learn, you have to work to know. That’s true in reality, and I tried to put it into that film. Black-and-white was right for that material. I’ve seen some films where the color-coordinated poverty was astonishing. I wasn’t prepared at that point to work out a rigorous scheme.

Q: You shot it almost as if we were eavesdropping or Peeping Toms. People go about their business, and the filmmaker seems to choose certain aspects or instances in their lives. We have to be observant as we watch.

BW: You must bring something to the film. You must fill in certain things, I think.

There’s a kind of selectivity in the framing and the choice of what scenes to include. That comes partly in the editing and the shooting. It’s the revealing details. Much of that detail was in the script. Some people want melodrama or high drama, but perhaps the lives of these people are not overly dramatic on a daily basis. Perhaps the drama exists on a level that we have to work to see — small nuances, telling details, tone, gestures, actions that are not so broad or overt.

Q: Where did you shoot the film?

BW: We shot it in south central LA, southwest LA, a little bit on the Long Beach pier, and in Watts. The barbershop is in Watts. He’s been there since 1933. He knows everything about the place. That’s Charles’ barber; he’s over 70 years old.

Q: What’s in store for you?

BW: At this point, I can’t really say what project I will do next. I am considering a number of them and a number of approaches. I hope that the possibilities of working will include a broader canvas in terms of the kinds of films that I can make in my lifetime. One does not necessarily have to make the same kind of film over and over.

At the same time, I am concerned with the reality of black people and our situation. Because not only does the black population not have its reality reflected in media–because we are not empowered to give expression to what we know and feel — but the larger audience and the larger public in this country are also not aware. People say my film is like a foreign film, it’s like a foreign country. But it’s 20 blocks from their homes and they haven’t been sensitized to want to look at it, to have the curiosity about it and come to know the reality.

Thank you to Indiana University Black Film Archives, Brian Graney and Rhonda Sewald for providing the interview.

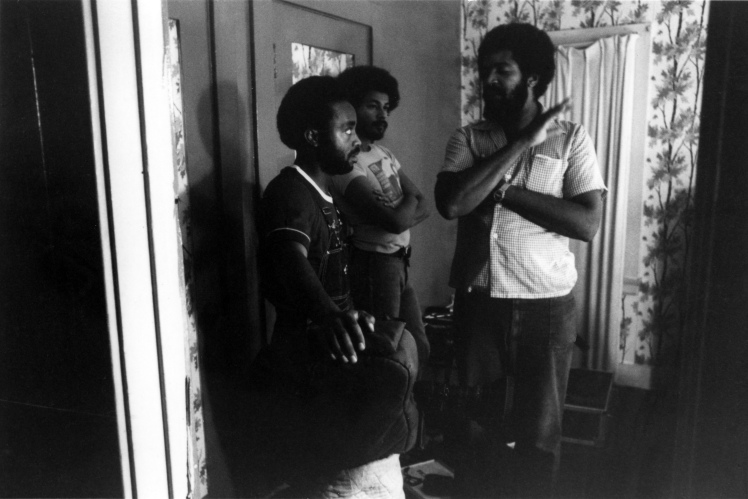

Bless their Little Hearts is a 1984 classic film directed by Billy Woodberry. It was honored by being selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. The restoration was carried out by Ross Lipman for the UCLA Film and Television Archive with funding by The National Film Preservation Foundation and The Packard Humanities Institute. Digital restoration by Milestone Film & Video with Re-Kino in Warsaw, Poland. Director Billy Woodberry (right), Bernard Nicolas (center) and screenwriter/cinematographer Charles Burnett (left)

Share this:

Bless their Little Hearts is a 1984 classic film directed by Billy Woodberry. It was honored by being selected for the National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. The restoration was carried out by Ross Lipman for the UCLA Film and Television Archive with funding by The National Film Preservation Foundation and The Packard Humanities Institute. Digital restoration by Milestone Film & Video with Re-Kino in Warsaw, Poland. Director Billy Woodberry (right), Bernard Nicolas (center) and screenwriter/cinematographer Charles Burnett (left)

Share this: