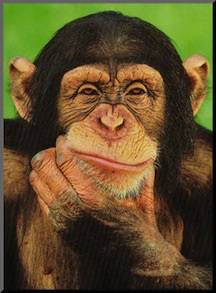

Because it is fun and improves my mind. Here is an excellent example of social praxis demonstrated in simians: PLOSone has a report of another experimental studies designed to investigate whether great apes, e.g., chimpanzees, bonobos, and orangutans, can distinguish another’s ‘false beliefs’ and act upon that discernment to help them. The researchers used procedures adapted from human studies that demonstrated some understanding of another’s false beliefs at 18 months of age and good understanding by age 3 or 4 years old. The researchers were very diligent in their design and implementation in order to ensure validity and reliability; I will give only a bare outline before going on to deeper issues. You can read for yourself at: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0173793

The basic set-up is this: Actor A comes into the room and puts an object in box 1 and then leaves the room. Actor B comes into the room and switches the object to box 2 and then leaves. Actor A returns. Which box does he go to? The subject has watched this whole scenario knows the object is in box 2 but also, if socially cognizant, knows that actor A believes the object to be box 1. In some protocols the visual gaze preference is measured, i.e., how long the subject looks at agent 1, box 1 and box 2, the assumption of this measure of passive action being that gazing more at box 2 shows awareness of the false belief. A more robust protocol is for the subject to move and help actor A open the correct box. And indeed the results show that young humans and the great apes move to show actor A the true location of the object, trying to help by correcting the false belief. More on this in a bit.

The basic set-up is also modified so that after placing the object in box 1, actor A stays in the room and watches actor B come in and move the object to box 2. I really like this variant; it shows the ingeniousness of scientists in clarifying the data’s interpretation.. When actor A goes to box 1 and tries to open it, little humans and great apes try to help him open box 1, seeming then to understand that actor A knows where the object is but wants to open box 1 for some other purpose. In another variation, if actor A opens box 1 and looks puzzled at not finding what was desired, subjects helped focus on box 2 and so retrieve the object.

Now when was the last time you had your keys?

I think this is a great study along the lines Frans de Waal calls for to help us understand how smart other animals are, and I have some quibbles and want to think about further examples of distinguishing false beliefs from human cultural and symbolic behavior. My first quibble is that in the abstract the researchers state that their results demonstrate that this type of social cognition and understanding, which had been thought to be exclusively human, might now be found in other animals. “Great apes thus may possess at least some basic understanding that an agent’s actions are based on her beliefs about reality. Hence, such understanding might not be the exclusive province of the human species.” If you have followed this blog at all, you know what my challenge will be. What anthropodenialist (see 4/8/16 post on de Waal) and all too precious human assumed (do I detect a false belief there?) this was to be found in humans only? Not good, especially in this day and age when we understand that human evolution includes no discontinuities with our ancestors. Research like this is not really changing our view of who we are (or at least it shouldn’t be) but rather reveals how the biological roots of our humanity grew our species.

Secondly, here is perhaps an obviously semantic quibble: Why call this false ‘belief’ when a much better word would be ‘assumption’, thereby reserving the word ‘belief’ for some thought formed with less ties to sensory data? Consider two known features here, mirroring and the kinesic communication of intent (a basic form of empathy). Mirroring cells in at least the primate cortex are motor cells that fire when the animal sees another perform an action (see many posts here about this, especially my most popular post of all time on the arcuate fasciculus, mirror cells, and memes). In the experiments described above, the subject animal, be it human or great ape, would respond through mirroring to the reappearance of actor A when approaching a box. Further, some studies have suggested that mirror cells are sensitive to the other’s intention, e.g., seeing the other pick up a cup, different cells fire when the other is going to drink from it as opposed to doing some other unrelated task. So the subject animal needs only mirroring and basic empathy coupled with environmental object mapping (quite evident in the rat brain) to identify the false assumption; the impulse to help would be again a basic empathic action that forms the incipient base of social praxis. (Remember watching somebody struggle to do something and your impulse to grab the object and do it for them?) The mirroring system may go a long way in offering some understanding of this social cognition, and the assumption of continuity in the perceptual world along with communicated intent is a basic, so that belief is not really a construct needed to understand this.

I always thought god was a bonobo, and now you tell me . . .

What about the broader, deeper phenomena of detecting (and responding to) another’s perceived false beliefs, real beliefs about abstract matters rather than perceptual data? We humans, at least, seem to have a talent for apprising others of their false beliefs. You know, like someone just knows I am going to hell because of my false beliefs? Or an example of more consequence, people who deny scientific findings because why? The false beliefs of scientists, of course, thereby exposing their own false beliefs, also called ignorance, about the nature and process of science. So much of our world, the human Umvelt, is dominated by symbolic information displaced in time and space, abstracted from experience and formulated with, at times, great creative license, that finding agreement rather than parsing others’ mistakes might seem the challenge. That, of course, is a function of culture, however, and oh, wait, is that part and parcel of the scientific method, and I hasten to add, the basis of democracy? Now, about the emperor’s new clothes . . .

Share this: